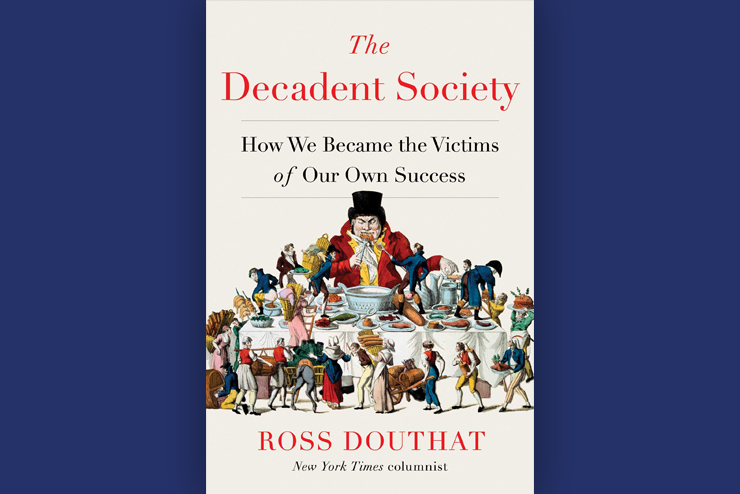

The Decadent Society: How We Became Victims of Our Own Success by Ross Douthat; Avid Reader Press; 272 pp., $27.00

The ancient latin aphorism per aspera ad astra (“through rough things, to the stars”) might well be a fitting epigraph for New York Times columnist Ross Douthat’s latest book. Its cover features a 19th century French illustration of Rabelais’ Gargantua et Pantagruel being fed sumptuous foods and attended to by “little people.”

For Douthat, Gargantua is modern America: interested only in “filling its own belly”; bored; lacking in initiative; and prone to avoiding rough things such as struggle and sacrifice. He begins by recalling the post-World War II drive to the stars that resulted in the “peak of human accomplishment”—the Apollo 11 moon landing. There were new frontiers to be discovered and an enthusiasm for expanding human experience. However, something happened after Apollo: Or more to the point, nothing happened.

In its decadence, America ceased caring about such ambitious projects and became more than happy to simply “eat, drink, and be merry.” Although Douthat speaks from within the Gargantuan regime he critiques, his counsel is wise: If we are to overcome this decadence, we must again embrace struggle and sacrifice.

Douthat has a tremendous command of literature, popular culture, and current trends, as well as an eye for striking historical parallels. His capacious mind is on impressive display in this book, which is an expanded version of a series of lectures he gave at Regent College in Vancouver in 2014.

He divides his brief into three parts. “The Four Horsemen” describes decadence in terms of economic stagnation, sterility, sclerosis in institutions, and repetition in culture that allows no genuinely new artistic or cultural achievement. “Sustainable Decadence” describes “the filling of the belly” and the attendant torpor of the American public even as a creeping if not explicit totalitarianism threatens. Finally, “The Death of Decadence” imagines ways that the Gargantua of decadence can be toppled, whether through some catastrophe, or by a cultural renaissance, or by an exitus-reditus, a return to God.

Following historian Jacques Barzun, Douthat notes that cultural decadence arises within:

a situation in which repetition is more the norm than innovation; in which sclerosis afflicts public institutions and private enterprises alike; in which intellectual life seems to go in circles; in which new developments in science, new exploratory projects, underdeliver compared with what people recently expected.

Ironically, this condition of stagnation often results from prior successes, which have been created by an unreal world funded by the few uber-rich and supported by a half-educated meritocratic elite. The virtual world of technology and entertainment that this class has created lulls to sleep the young men who should be driven by noble ambitions. Instead, they seem content with their videogames and bottomless pits of virtual sex.

Among the shrinking middle classes, initiative, innovation, and the sheer capacity for wonder have all been stifled, even as birthrates decline and marriage becomes all but obsolete. Douthat employs metaphorically the term sclerosis, usually associated medically with a hyperplasia of the connective tissue or a hardening of the arteries, to suggest that our vital life force is not so much spent as it is trapped in circularity, a vicious cycle of repetition.

Possibly the most sclerotic of our institutions is the federal government (and the state governments which have been reduced to mere appendages of the managerial monolith). The Constitution and its elegant separation of powers has been ignored and replaced by the diktats of a bureaucratic state. Reform of the government, particularly any attempt to return to the intent of the founders, is a fool’s errand, especially so in this age of extreme political polarization.

In one of the finest analyses of the book, Douthat looks at authorities in the modern West and their “strategy of control.” By contrast with the regimes of the past, control is today exercised in a more decentralized fashion. Douthat is not the first to note that what is emerging in the Western nations is a regime that might be called a police state with liberal characteristics—a seemingly oxymoronic formulation, but one with some truth.

This new sort of police state with a compassionate face is both shaped and constrained by the West’s individualism and emphasis on human rights. “But it will still have an authoritarian edge—a gently despotic aspect—under a banner that isn’t the red of Communism or the black and brown of fascism, but a friendly, helpful, cheerful color.”

Of course, this Brave New World of decadence isn’t all so bad. Indeed, as long as we have our “soma”—the ubiquity of pot dispensaries, 24/7 porn on our devices, and a kindly despotism—we won’t mind the control, right?

In the last section of the book, Douthat tries his hand at prophecy, attempting to forecast what might get us out of this decadence. Catastrophe is a possibility. Here he describes several dystopian scenarios, environmental or migratory, for example, which might lead to a new beginning, as in the apocalyptic Mad Max films. More hopefully, Douthat suggests the possibility of a renaissance in religion and culture.

How might this happen? Here he references Cardinal Robert Sarah, the African prelate who has frequently voiced his alarm at the rapid decline of the Christian faith in Europe. Unlike Sarah, however, who is adamantly opposed to African migration to Europe, Douthat speaks of a potentially flourishing Christian African continent migrating north to the older seat of Christendom, reminiscent of Evelyn Waugh’s short story “Out of Depth,” in which a future dystopian England is served and saved by African missionaries.

Where Sarah sees the dangerous potential for Muslim exploitation of an African diaspora into Europe, however Christian it might be initially, Douthat envisions the great cathedrals of Europe packed with vibrant African Christians. He imagines that in our current malaise there are indications of a “yearning for an out-of-Africa renaissance, for an African-shaped future that’s dynamic rather than dystopian: Make Africa Great, and then Make the World Great Again As Well.”

Frankly, this is not so far removed from the scenarios projected by the true believers in beneficent alien civilizations, à la Carl Sagan, who believe that our cosmic saviors will miraculously appear at the moment of our greatest crisis and lead us toward a new awakening of humanity.

Frankly, this is not so far removed from the scenarios projected by the true believers in beneficent alien civilizations, à la Carl Sagan, who believe that our cosmic saviors will miraculously appear at the moment of our greatest crisis and lead us toward a new awakening of humanity.

To be fair to Douthat, he does a thorough job of analyzing our decadent society from several perspectives—cultural, political, and philosophical. He rightly insists that decadence has interconnected economic, demographic, intellectual, and cultural factors. “You just can’t pick out a single cause or driver of stagnation and repetition, or solve the problem with a narrow focus on one area or issue,” he writes.

However, it is evident throughout the book that Douthat is a member of the conservative establishment. His is the proper pedigree from the approved Ivy League school, and he never passes up an opportunity to criticize President Trump or his administration, sounding at times like the haughty Gore Vidal in his criticism of Ronald Reagan (“an aging juvenile actor”) during the celebrated Buckley-Vidal debates in 1968.

Indeed, as much as Douthat comments on and promotes the need for innovation and initiative, he cannot fully make the leap to the other side. He candidly admits—to his credit—that he did not cast a vote for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. Instead, he succumbed to the comfort of the very decadence that he criticizes, preferring, it seems, the Obamas and Romneys of the political establishment over something truly different. Whatever one might think of Trump’s populism, it is surely an attempt, however flawed, to break free of the “liberal despotism” that Douthat claims to deplore.

Perhaps the American people, by instinct if not erudition, are ahead of the curve in their desire to see the decadence shaken up—that is, in their willingness to go through something potentially rough. Perhaps in their inherent good sense they understand that the current situation can indeed change, though the transition may be inelegant.

Yet whatever reservations one might have about Douthat’s political preferences, he must be praised for recognizing the fundamental fact—forgotten by our betters who have succumbed to the ancient temptation “to be like gods”—that in the midst of this crisis in our national life we should be down on our knees. For it is only through prayerful humility that we will begin to see the path leading out of our decadence.

Leave a Reply