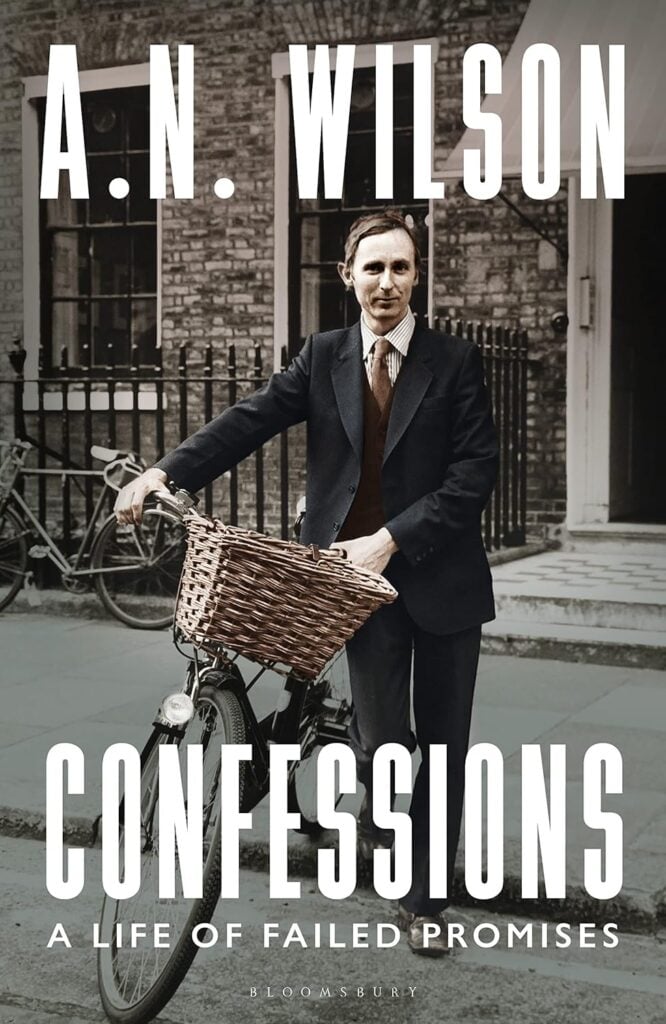

Confessions: A Life of Failed Promises

by A. N. Wilson

Bloomsbury Continuum

320 pp., $30.00

Andrew Norman (“A. N.”) Wilson is not well-known in this country, but he should be. Unbelievably prolific, he is the author of 50 books and more than a million published words. He’s a prize-winning novelist, biographer, and journalist, but, more than that, he’s akin to a higher life-form. Most likely a genius, he is in command of several languages and was a teacher of Old and Middle English at Oxford. Later in life he picked up German in order better to understand Goethe, and Russian in order to write a magnificent biography of one of his idols, Leo Tolstoy. I have written in these pages (“What We Are Reading,” February 2022 Chronicles) of his brilliant, quirky biography of his friend, the dazzling fellow Oxonian novelist, Iris Murdoch, and now we have from Wilson his Confessions.

The title recalls the two great predecessor “Confessions,” St. Augustine’s and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s. This book is more like the former and illustrates a life-long struggle to come to terms with, among other things, faith. He describes himself as “a confused, and very disobedient, Christian,” and he tells of some time spent in seminary, toying with the idea of becoming an Anglican priest (as a younger man he flirted with Catholicism, but he was born and eventually remained Church of England). Much of what he recounts here is his intermittent embrace of belief, and his repeated succumbing to agnosticism. But if Wilson can’t quite bring himself to believe, he is extraordinary at discussing the faith of his many friends and acquaintances, and the religious odyssey that he presents here, is, in the end, a joyful and hopeful one. The book would be worth reading for that story alone, but it is only one rich theme of many in this delightful volume.

In what may or may not be intended irony, Wilson’s subtitle of his Confessions is “A Life of Failed Promises,” and he claims to have fallen short in six ways: as a writer, as a human being, as a husband, as a parent, as a son, and as a friend. This engaging work is probably best read as a refutation of each of those six purported failures.

As a writer, Wilson suggests he is not “worthy to lick the boots” of the truly great, such as Tolstoy or Jane Austen, but his many prizes and the mere perusal of his shimmering prose in these Confessions belie the notion that he’s a literary flop. His possibly false modesty on this point is amusing, as he also claims to be a “minor British author,” and, reflecting upon being photographed in 1983 in a group Granta Magazine proclaimed to be the “Best of Young British Novelists,” Wilson remarked that he and his fellows were “a gang of Salieris with not a Mozart among them.” Wilson may justly feel disappointment at never winning the Palme d’Or of British authorship, the Booker Prize, but that award seemed to become increasingly political in the late 20th century, and Wilson, who was at least a fellow traveler on the right, would have been an unlikely pick.

If the purpose of human beings is to bring joy to their fellows, Wilson has failed to fail at that as well, given the many gems found here. The book ends roughly halfway through his life, with the death of his father and with him beginning his biography of Tolstoy, but what he tells us of his many relationships, his literary efforts, and the breadth of his experience, even at the halfway point, reveals an enviable and remarkably vital life.

Wilson does limn a fair case for his having failed as a husband, at least with regard to his first marriage to the celebrated Shakespearian scholar and Oxford don Katherine Duncan-Jones, a woman nine years his senior. Like the Bard, Wilson found himself in this marriage to an older woman he may not have loved (and who loved another man) because Duncan-Jones was pregnant with Wilson’s child, and, again like Shakespeare, Wilson more or less abandoned his family and went to live in London, where he proceeded to engage in various infidelities. The marriage ended in divorce after 19 years, and Wilson writes he and “K,” as he calls her, were both miserable in it, but some of the most poignant parts of the book deal with Wilson’s diligent visits to his former spouse as she remained in Oxford, at the end of her life, in late-stage dementia. (The same ailment, it is interesting to note, befell Wilson’s cherished Iris Murdoch!)

Wilson’s claim that he failed as a father rests on his fleeing to London and leaving the two daughters from his first marriage behind, but one of those daughters, Emily, became a brilliant classicist at the University of Pennsylvania, the first woman to publish a translation of Homer’s Odyssey into English, and a MacArthur “genius grant” recipient. The other, Beatrice, was an undergraduate and graduate student at Cambridge, has published seven books on cooking and the history of food, was formerly a columnist for the New Statesman and the Sunday Telegraph, and is the “Table Talk” columnist for the Wall Street Journal. Wilson indicates pride not only in these two, but also in his third daughter, from his second marriage (a union more successful than his first), who went on to art school. This is not to say that the sine qua non of worthiness for a woman is a professional career outside the home. In our woeful world of fractured families it might be more important and more courageous to be a full-time mother and homemaker. Still, if what became of Wilson’s progeny indicates failure as a parent, then failure as a parent isn’t what it was when I was young.

Wilson presents some material implying he did manage to fail as a son, at least in his early years. He explains that he loathed both his parents—his father, the chief operational officer for the famous Wedgwood pottery manufacturer, and his mother, a bright but perpetually dissatisfied and angry middle-class matron. He says he was far fonder of his nursemaid; still, his father looms large in the book, which ends with his dad’s death, and Wilson does indicate that he became closer to both parents in their old age. Even more interesting, he credits them with encouraging his career as a writer, and he doesn’t conceal his admiration for his father’s aesthetic and administrative abilities. It’s not explicit, but if his parents weren’t proud of their son, they would have to have been far more inhuman than he portrays them.

It is Wilson’s assertion that he failed as a friend that is most ludicrous, as the book is a sparkling catalogue of the great, the near great, and the exceptionally interesting with whom he mingled, in both London and Oxford. Wilson seems to have been close to the Queen’s sister, Margaret, to the Queen Mother, to the Queen of Denmark, and to several of his fellow novelists (some of whom are pictured with him in that 1983 photo). He was chosen as his friend Iris Murdoch’s official biographer and among his many other literary chums were Christopher Tolkien (son of the author of The Lord of the Rings), Kitty and Malcolm Muggeridge (“the best conversationalists” he ever knew), Peter Ackroyd, Caroline Blackwood, and Beryl Bainbridge.

Such a galaxy of talent, royalty, and fame must have seen something in A. N., and one suspects it was a superhuman amount of wit, warmth, and charm. Regrets he has a few, however—stemming from his journalist’s tendency to kiss and tell. His indiscretions did lose him a few of his famous friends, and particularly unforgivable, perhaps, was his tendency to gossip in print about the Royal Family (the Queen Mother hated socialists, Princess Margaret drank too much, was lonely, and believed in the divine right of kings, her nephew, Charles, the then Prince of Wales, was a “committed lefty who probably would not have minded … were the monarchy to be abolished,” and Charles’ mother, Elizabeth, according to her mother, “had no aesthetic sense.”) One squirms while reading all this and finds unconvincing Wilson’s excuse that these garrulous royals knew he was a journalist and that, besides, at the time he was publishing these indiscretions, “The Prince of Wales and his wife were going on television, quite unnecessarily, to admit adultery.”

Still, the book is a fine and deep reflection on the institution of friendship itself. Wilson claims he had no “true friendships” until he was 20, but found, as an adult, that “Friendship in my experience is a deeper thing than love.” Even more intriguing are his observations that his friendships kept him from going mad during his first marriage; that marriage, for most people, “is destructive of the human soul;” and yet he declares, “There is no relationship happier than friendship between a man and a woman. Friendship between two men seldom involves the sharing of confidences.”

This may not be Samuel Pepys’ diary, or Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, but it is as a good a portrayal of the glittering London and Oxford literary life in the ’70s and ’80s as we are ever likely to get. It is also a profound and provocatively unique exegesis of the human condition, rendered with a light touch by a modern master.

Leave a Reply