“Poetry is the language of a state of crisis.”

—Stephane Mallarme

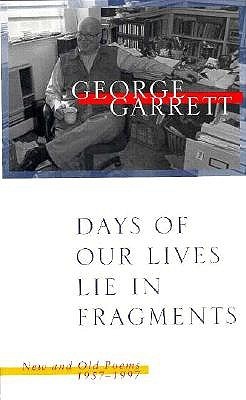

One of the most important things to say about George Garrett is that his is a generous talent, not limited or confined by a narrow point of view. It is as though he has been searching for the meaning of life in many ways and modes of expression, including novels, short stories, and critical studies, to give only a partial list. And, of course, poetry, always poetry: The Reverend Ghost (1957), The Sleeping Gypsy (1958), Abraham’s Knife (1961), For a Bitter Season (1967), Welcome to the Medicine Show (1978), and Luck’s Shining Child (1981). The present volume, Days of Our Lives Lie in Fragments: New and Old Poems, 1957-1997, is a judicious selection from these collections and 30 new poems, spanning over 40 years.

Garrett has always been something of an “outsider,” refusing to go along with contemporary dogma both literary and political, at the same time that he has been in his amiable way an “insider” with a wide acquaintance among writers, and wishing, one feels, that he could assume the impossible role of peacemaker among the warring factions that distress our times. Consequently, he is a seminal figure reflecting our contemporary restlessness as he searches for some kind of rapprochement, not finding it altogether but not giving up either: “there are things so beautiful / and strange the mind can’t hold / them though it wrestles” (“The Angels”).

The title of the new collection is well-taken, faintly echoing T.S. Eliot’s “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” The poems encompass all the variety one could wish for: poems about everyday experiences, a moving tribute to O.B. Hardison, the brilliant scholar who died too young, poems that refer to such literary friends as Brendan Calvin and John Ciardi, among others. One catches one’s breath, and continues: poems that illustrate a wide interest in literature and art, the quotidian in tandem with the lofty and extraordinary. A lively and sympathetic interest in his students is apparent, and he must be a delightful teacher. The remarkable poem, “Out on the Circuit,” is an account of the underlying horror of giving a poetry reading that should curl the hair of any ambitious young poet. And yet one feels that he carried off the mission with aplomb. There are many other examples in the book of Garrett the survivor, who has been able to make his way through the circumstances of our times, experiencing them but not being overwhelmed by them. In another life, he might have been a diplomat, wary and watchful, looking for a sane and civilized solution to many of our problems.

It is worth noting that without the modishness of the “confessional” poet, an informal, non-chronological autobiography emerges from these “fragments” as they accumulate. We learn of the many places he has lived, his devotion to wife and children, his love of women in general —few contemporary poets have written so lyrically, and sometimes voluptuously, about them. In the delightful poem “Grapes,” we learn that he has been a soldier in Tuscany and, in the final poem of the book, “Holy Week,” that he is a religious man. “The Magi” and other biblical poems confirm this fact.

Technically, the poems are smooth and fluent, employing a free verse that is not all that free. The early poems make an adept use of rhyme and meter, and they are an echoing presence in the later work. You feel that Garrett could easily slip back into rhyme if the occasion and subject were right and that he would not be awkward or ill at ease in doing so. One remembers that Amy Lowell, the Mother Superior of Imagism, insisted that the young poet should have a firm grounding and practice in traditional poetry before attempting free verse. In any case, Garrett is not prejudiced only in favor of untrammeled liberty, and would probably not argue with Byron’s dictum: “Easy writing makes hard reading.” The conviction arises from the poems that he knows all the fashionable creeds and attitudes about technique but can put on blinders when he wants to, and that he would not quarrel with Wallace Stevens’ notion that the only useful thing to be said about technique is that the poet should be free in whatever form he uses.

Surprisingly, the Southern landscape does not hover in the background in many of these poems by a native Floridian. Urbane and cosmopolitan, rather than regional, Garrett does not belong entirely to any actual place or landscape of the mind (unlike Robert Frost, whose North of Boston is a constant background and who could say of himself early on: “they would not find me changed from him they knew— / only more sure of all I thought was true”). But then, perhaps, our fragmented society requires a more roving perspective, a kind of going here and there. There is no doubt that Garrett has “gotten around,” “made the scene,” and extracted as much as he could from these experiences, dismal though they sometimes were.

But, for the most part, the lasting aura of the poems is genial, and gives off the glow of a pleasant man who remembers the essence of Isak Dinesen’s “I do not come for pity, I will come for pleasure.” This is rare enough among literary personalities to be worth: emphasizing. Too often we admire the work, and, alas, deplore the author.

Has Garrett found life, particularly the literary life, worthwhile and satisfying? Yes and no. We find him constantly aware of the loss of traditional values with little else of value to put in their place. A number of poems convey the sadness and cultural malaise of Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Each torpid turn of the world has such disinherited children / To whom no longer what has been, and not yet what is coming, belongs.” At the same time, as I have suggested before, there is an incurable optimism in Garrett’s nature in spite of the cultural stranglehold. After a poem about “gray thoughts dark laughter cold words” (“Pathetic Fallacy”), followed by “Gray on Gray,” he gives us a very happy poem indeed, brief enough to quote in its entirety:

How It Is How It Was

How It Will Be

How it is

on the next day after

the blizzard

how the sky clears blues brightens

cloudless and clean with the old

moonfloating here and there quiet and

grinningand the quiet fallen snow

glinting winking glittering

(is there one and only word for it?)

with abundance opulence

extravaganceof (one and only) sunlight

how mv breath and the river’s

do steam and ghost and

shimmyshakein this purely cold air

how now we know

that we shall surely live forever

how now we want to.

Perhaps his credo emerges best of all from a poem entitled “Postcard,” which, ironically, is a good deal longer than any postcard I ever received, but then, as I have said, George Garrett is a generous

“Dear World, though I have loved you

and lost you, times beyond counting,

still I write upon this instant in receipt

of all your ordinary music to inform you

that I can’t live without you.

I intend, by God, hell and high water,

sleet or snow and the wheel of fortune,

to come back for more of the same. . . . “

This is enough for any man to believe in these days. The dust jacket states that Garrett’s reputation rests mainly on his fiction. This fine collection demonstrates that it should include his poetry as well.

[Days of Our Lives Lie in Fragments: New and Old Poems, 1957-1997, by George Garrett (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press) 222 pp., $26.95]

Leave a Reply