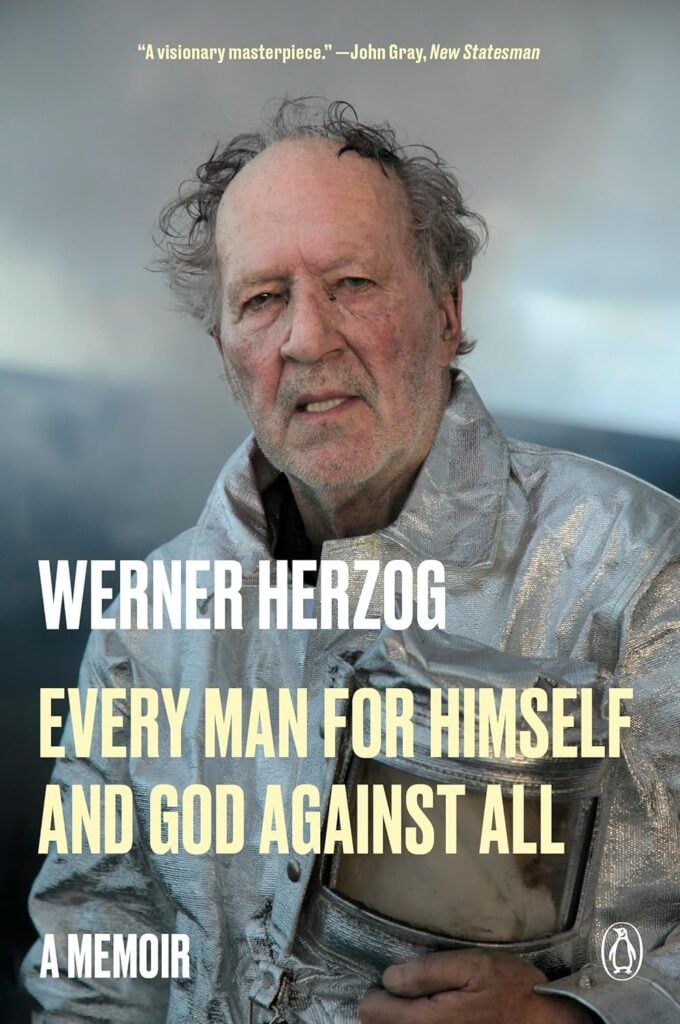

Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir

by Werner Herzog

Penguin Press

368 pp., $30.00

Throughout his long career in film, director Werner Herzog has escaped aesthetic categorization. In his more than 70 films, Herzog consistently looks outward, examining people, animals, and distant places. In his new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, however, Herzog turns his attention to himself, and singles out essential elements of his life that have given birth to ideas, perceptions, and films.

Herzog describes a unique and strange childhood that may explain why he defies categorization. Unlike many directors, whose path toward filmmaking is marked by the experience of cinema itself, Herzog chose the medium for reasons not typical of others in his generation. Growing up in Bavaria toward the end of World War II, he didn’t even know about movies until he was 11 years-old. “I had no notion of cinema,” writes Herzog. “I didn’t know such a thing existed until one day a man with a mobile projector came to us in our one-room village school in Sachrang and showed us a couple of films, which utterly failed to impress me.”

One can almost hear Herzog’s unique voice—English spoken flatly, plainly in not merely a German but Bavarian accent.

Herzog’s book is replete with honest discussion about the sometimes-cruel nature of the human condition—without endless disclaimers or insertions of ideology. It is precisely this raw side of the human condition that inspires him. Pura vida, a phrase he first heard in Mexico, has become something central to his work. Herzog recalls a moment when he “leapt down out of the window,” and ended up nearly biting his tongue off upon the fall. A man then told him this was just part of life, part of pura vida, but “what he meant wasn’t the purity of life, as with the early saints, but the sheer, brute, unpredictable, overwhelming presence of life.”

It’s not entirely possible to separate Herzog’s life from his work because he gives himself completely to it. Sometimes foolishly, but mostly out of a driving sense of curiosity, Herzog has found himself in the most obscure corners of the world. Intrigued by the subjects, his films show someone who is not a mere observer but a detective devoted to uncovering the secrets of humanity.

Herzog sees life in an unusual way, yet it is a way that makes sense to his audience. He singles out events that we may otherwise miss, and creates a meaningful confrontation with them. This method of observation comes from his childhood. He reflects on his life after the war, and what small acts of compassion meant to him. “Shortly after the war ended,” writes Herzog, “the first CARE packages started to arrive that helped us through the worst, thanks to the Marshall Plan. I will always be grateful to America for them … one of the earliest packets contained a book, printed like a large schoolbook: Winnie the Pooh. I bow to the intelligence and compassion it must have taken to throw in something like that. Probably no one knows who had such an idea, but my respect goes to the man or woman responsible.”

Herzog’s childhood was dark. His father abandoned the family and they endured grinding poverty following the war. He writes that he had “brooding” tendencies but even in his early years he possessed a desire to know and explore. He considers himself metaphysically separated from Germany, but “in terms of culture,” Herzog writes, “I am Bavarian. Bavarian is my first language; the landscape is my landscape, and I know where home is.”

One of the surprising elements of Herzog’s life is his youthful conversion to Catholicism. Being an adventurer by inclination, however, religion proved to be too much of a constraint for Herzog. Although he does not think of himself as an atheist, the hierarchal structure of the Catholic Church (among other things) was an obstacle.

His drive to explore beyond the obvious also causes Herzog to resist any structure created by human beings. Yet at the same time, he does not embrace chaos, fall into a Nietzschean abyss, or escape into a Dionysian pursuit of ecstasy. If anything, Herzog is methodical, logical, and supremely aware of the chaos inflicted on us by nature—a chaos that he suggests humans tend to recreate.

Herzog often faced this kind of tornadic chaos in his filmmaking. One example that stands out is his collaboration with German actor Klaus Kinski. Although they made only five films together, Kinski’s strange insanity left an indelible mark on Herzog’s work. He describes much of it in his 1999 documentary, My Best Fiend, and in this latest memoir, Herzog gives it some attention also.

Most people were afraid of Kinski, but not Herzog. He is remarkably logical and emotionally distant from the violence and chaos that Kinski brought with him. Yet it was this energy that caused some of the most powerful scenes in cinema. When he was just 13, Herzog first encountered Kinski who was then 26. Herzog’s mother and brothers rented an apartment in a building that happened also to have another tenant who “squatted in an empty attic,” namely Klaus Kinski.

Herzog remembers him as “an opponent of all forms of civilization … [who] never wore clothes when he was at home.” Everyone tried to stay away from Kinski but Herzog found him to be fascinating. “Aside from my mother,” writes Herzog, “I was the one who was not afraid of him. To me, he was a force of nature; it was like watching the devastation wrought by a passing tornado.”

During the filming of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, things became so violent that one of the indigenous people asked Herzog if he would like him to kill Kinski. The approach Herzog took in dealing with Kinski was always one of calmness and logic with a dose of strangely displaced fatherly disapproval. But even Herzog could not keep going. At some point, the relationship had to be severed.

One of the things about Herzog that has always been refreshing is his honesty. His inherent disdain for political correctness and consistent push against all forms of ideology are just two of his stances that make Herzog a genuinely fascinating artist. To be sure, he makes judgments, and does not subscribe to any fairy tales about people. There are never moments of equivocation, or of seeking to make one group feel superior to another. Herzog is not bound by either liberalism or conservatism, or by any kind of politics whatever. He is certainly unconcerned with being accepted or rejected by either critics or fans.

Herzog does not provoke in the vulgar sense. He does, however, seek to jolt his audience from the slumber of the self. This can be seen in the way his films reflect his desire to step outside of himself. “I have a deep aversion to too much introspection, to navel-gazing,” he writes.

I’d rather die than go to an analyst, because it’s my view that something fundamentally wrong happens there. If you harshly light every corner of a house, the house will become uninhabitable. It’s like that with your soul … I am convinced that it’s psychoanalysis—along with quite a few other mistakes—that has made the twentieth century so terrible.

Herzog’s poetic honesty is refreshing in our time of dull and joyless self-obsession.

Reflecting on his 2010 documentary film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, about the Chauvet Cave in France, Herzog writes about his own “hunger for transcendence,” even before his discovery of Catholicism. He was in his early teens, living in Munich. One day, he passed by a bookstore and saw a “book about cave paintings, and the picture was one of the celebrated wall paintings from the caves at Lascaux. Herzog saved enough money in the hope the book would still be available. He was lucky. Managing to buy the book, Herzog writes, “The shiver I felt when I opened it and turned the pages and saw the illustrations has never left me.”

Since the filming conditions in the cave were difficult, the crew had to be small, and Herzog was permitted to work only four hours per day. This did not stop him from making a documentary that goes beyond mere historical facts. As if inspired by the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, who expressed metaphysical aspects of time and objects, Herzog takes the notion of memory and history, and shapes it into a philosophical and poetic offering. Who are these people who came before us?

“I was always fascinated,” Herzog, writes,

by the way collective memory is sometimes evinced from the depths of time … is there something like buried memory within families? Or, to put it differently, are there images that slumber within us and are sometimes set free by some sort of jolt? I believe so, and somehow all my works have pursued such images, whether it was the ten thousand windmills of Crete in my first feature film, Signs of Life, or the steamship that is lugged over a mountain, the central metaphor of my film Fitzcarraldo. I know it’s a wonderful metaphor, but what it means I am unable to say.

An artist is always looking for a way to illuminate and express the ineffable that is contained within our world. Despite the fact that Herzog is “unable to say” exactly what this is, he has created and continues to create works of pure art that call us to reflect on our humanity.

“How can something unimaginable be possible? I have never closed my mind to that question,” Herzog writes. His artistic perseverance is just as much a species of courage as that possessed by any explorer he ever filmed. His question is at the very core of being human—a finite being striving to reach the infinite.

Leave a Reply