“A politician . . . one that would circumvent God.”

—William Shakespeare

Initially, Kevin Phillips intended his new book, American Dynasty, to be a study of

the Bush-related transformation of the U.S. presidency into an increasingly dynastic office, a change with profound consequences for the American Republic, given the factors of family bias, domestic special interests, and foreign grudges that the Bushes, father and son, brought into the White House.

As his extensive research progressed, the scope of his effort broadened considerably and became a careful study of four generations of the Bush family’s deep and active involvement in “crony capitalism,” the petroleum business, national-security and intelligence organizations and operations, investment banking, influence-wielding and -peddling, and the incestuous relationship between industry and government, particularly as it involves military preparedness and actions.

Old habits die hard, especially where the use of moral terminology is concerned. In the 1850’s, James Smith Bush, George W.’s great-great-grandfather, graduated from Yale and became an Episcopal minister in New York. There is limited reference to the Reverend Bush in Phillips’ book, but we have every reason to believe that he was a moral and spiritual man. He was the last male member of the Bush family not to devote his life to business, finance, oil, money, and politics. Nonetheless, the four generations that succeeded him have continued to stress their integrity in the most moral of terms. Since they ask us to believe that they are men committed to honor, integrity, and duty, it is fair to look into how well they have succeeded. Phillips writes:

Before the election of 1988, George H.W. Bush had visited that year’s Christian Booksellers’ Association convention in Dallas to talk about George Bush: Man of Integrity, a book that discussed the family’s close relationship with evangelists Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell. In 1995, at George W.’s gubernatorial inauguration, Billy Graham had referred to “the moral and spiritual example his mother and father set for us all.”

Graham, that sycophant and spiritual advisor to any U.S. president willing to use him, has played an important role in the Bush saga. During the summer of 1985, Graham was visiting the Bushes at Kennebunkport and was able to help bring the lost soul, George W., “to God and salvation.” That was the beginning of what we might call a marriage made in Heaven. Most of us are familiar with George W.’s “born again” experience; however, not until I read Phillips’ book was I aware of Number 41’s transformation.

The son was not the only family member listening to the Religious Right. Campaign officials who shrugged off George W.’s influence on his father were ignoring the transformation of George and Barbara Bush. By the end of the summer of 1986, they had invited Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker for a visit, telling them how much they enjoyed watching The P.T.L. Club on television. The vice president also appeared at Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University, and discussed his own born-again “life-changing experiences” in a video that was shown to evangelical leaders.

It seems, however, that the Lord spoke to George the Father in the most universal of terms, certainly broad enough to include Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church. Notwithstanding Big George’s avowed acceptance of Jesus Christ as his Personal Savior, Phillips reports that,

During 1995 and 1996, two years after leaving the White House, he made at least nine paid appearances in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Tokyo, Washington, and elsewhere on behalf of Moon. The Korean businessman and evangelist, who dismissed Jesus as a failure and styled himself “the Lord of the Second Advent,” was said to be paying the former president $100,000 per speech. . . . The forty-first president, who told Argentine president Carlos Menem that he had joined Moon in Buenos Aires for the money, had actually known the Korean reasonably well for decades. Their relationship went back to the overlap between Bush’s one-year tenure as CIA director (1976) and the arrival in Washington of Moon, whose Unification Church was widely reported to be a front group for the South Korean Central Intelligence Agency.

I choose not to question the sincerity of George W.’s conversion and faith, however. Unlike his father, whose deeds defy and defile his words, he may well be a true believer even if he uses his beliefs to obtain political support and votes.

Last summer, the House and Senate Intelligence Committees prepared a joint report concerning September 11 and how it might have been prevented. Before the report was released, the Bush White House demanded certain deletions, including a 28-page section relating to the Saudis. However painful it is, I must agree this one time with Sen. Charles E. Schumer, who said, “There seems to be a systematic strategy of coddling and cover-up when it comes to the Saudis.” The fact remains: Two U.S. presidents named Bush have been deeply and personally involved both commercially and politically in Saudi Arabia, one of the world’s hottest spots.

Bush Sr.’s close ties to the Saudis go back at least to his brief CIA directorship in 1976, when his agency was helping to modernize Saudi intelligence, although it is difficult to believe that he had no contact with the Saudis during his 1971-72 service as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. As vice president and as chairman of the Reagan administration’s task force on energy deregulation, Bush Sr. sought to upgrade his petroleum-industry credentials. Phillips exposes the many business and personal ties between the Bushes and the royal family of Saudi Arabia that continue until the present. So close was Bush Sr.’s relationship to the Saudis that “the Saudi ambassador in Washington, Prince Bandar, and his wife considered the Bushes ‘almost family.’” Also, according to the authors of The Outlaw Bank, an account of the corrupt Bank of Credit and Commerce (BCCI), which involved prominent Saudi investors, Bush Sr. “was known throughout the Middle East as ‘the Saudi Vice President.’” Kevin Phillips writes that “no other political family in the United States has had anything remotely resembling the Bushes’ four decade relationship with the Saudi royal family and the oil sheiks of the Persian Gulf.” All of the arrangements—“arms deals and oil deals and consultancies,” according to William Hartung of the World Policy Institute—have made our government reluctant to investigate the Saudis.

The Carlyle Group was founded as a merchant bank or private equity house in 1987 and is unofficially valued at nearly $15 billion in funds under management. The group is so secretive that even highly competent and experienced reporters have difficulty explaining the exact nature of the enterprise. Investors invest in the various Carlyle funds—e.g., the Carlyle Asian Investment Fund—which have holdings throughout the world in businesses that furnish military, security, and related goods and services to governments and their various agencies. The Carlyle Group is an integral part of the Military-Industrial-Government Complex and sells, among other things, its experience with government officials in the United States and around the world. Its motto could be “We are the whores who open the doors.” Among the group’s more prominent members are the arrogant and pompous former secretary of state and secretary of the treasury James A. Baker III; former secretary of defense and deputy director of the CIA Frank C. Carlucci; former White House budget advisor Richard Darman; and former U.S. president, vice president, and CIA director George Herbert Walker Bush. Among its high-profile non-U.S. members are former British prime minister John Major and former president of the Philippines Fidel Ramos. Bush Sr. and Major have made vast sums of money advising Carlyle where to invest overseas, establishing contacts with foreign leaders, and giving speeches on behalf of the group. Bush’s speaking fees are then placed into his various Carlyle accounts. Until shortly after September 11, the Bin Laden family of Saudi Arabia had substantial investments in the Carlyle Group.

Every day, President Bush and his Cabinet make decisions that can financially benefit former President Bush and his cronies at Carlyle. And, in time, George W. figures to benefit from his father’s investments. Without question, George H.W. Bush should have withdrawn completely from the Carlyle Group when his son became President.

Bush Sr., since leaving office, has traveled on behalf of Carlyle, most often to Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf. He also helps recruit investors for the Carlyle funds. Phillips writes that 12 wealthy Saudi families and individuals, including the Bin Laden family, became investors before September 11. In 2002, the Washington Post reported that “Saudis close to Prince Sultan, the Saudi Defense Minister, were encouraged to put money into Carlyle as a favor to the elder Bush.” And President Bush appointed a Texas lawyer named Robert Jordan ambassador to Saudi Arabia. Jordan, a partner in Houston’s Baker Botts, the law firm of the Carlyle Group, represented George W. when he was investigated for insider trading with regard to his Harken Energy stock. One big cozy family: Bush Sr., Bush Jr., Baker (as in James A.) Botts, Jordan, and Carlyle.

Bush Sr.’s son Marvin appears to have done quite well in security-related businesses. Before September 11, World Trade Center security was handled for several years by Securacom (now Stratasec), a company in which Marvin was director and (along with the Kuwait-American Corporation) a major shareholder. “In 1997, security contracts with the World Trade Center and Washington’s Dulles Airport brought in 75% of Securacom’s revenues,” according to Phillips. Shortly after September 11, Marvin became a large shareholder through his investment firm in Sybase, which put banks throughout the world in compliance with the anti-money-laundering provisions of the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act. Their service is called the “Sybase Patriot Compliance Solution.” Homeland security has been quite profitable for those with close ties to federal departments and agencies.

Bush Sr.’s son Neil first gained notoriety as a director of the looted Silverado Savings and Loan. While on Silverado’s board, Neil set up an “oil company” named JNB Explorations with two partners, Ken Good and Bill Walters, both contributors to his father’s campaign. Neil overlooked telling his fellow board members at Silverado of his close connections to Good and Walters. While Neil, who received a $100,000 loan from Good with no obligation to pay it back, was on the board, Silverado made over $200 million in loans to Neil’s partners in JNB. Those loans were largely defaulted, so we taxpayers know who paid them.

Son John Ellis Bush, better known as Governor Jeb, moved to Miami in 1980 and went into the investment and real-estate businesses. According to Phillips, Jeb participated “in controversial financing of office buildings through savings and loan institutions that later became insolvent.” In 1985, with Armando Cordina, he bought an office building financed by Broward Federal Savings and Loan. When Broward failed a few years later, the federal Resolution Trust Corporation took over the defaulted Bush-Cordina loan. The two investors made a deal with the feds: In exchange for a payment of $500,000, the regulators agreed not to foreclose on the office building. The remaining loan of $4.1 million was paid for by—you guessed it—the taxpayers. A few million for Neil, a few million for Jeb, and, before you know it, we are talking about real money.

After the conclusion of Gulf War I and following Bush Sr.’s term as President, James A. Baker III and former Bush Sr. commerce secretary Robert Mosbacher were hired by Enron “under a joint consulting and investing arrangement” by which they would participate in the profits from any natural-gas projects they developed worldwide. On one of the Enron trips to Kuwait in 1993, Baker and Bush Sr. took along Marvin and Neil as lobbyists for Enron and for themselves.

Any other connections between Enron and the Bushes? Well, let’s see: Bush Sr. and Ken Lay appear to have met in 1980. George W. claims that he first came to know Lay in 1987, but it could have been earlier. By Election Day 1988, Lay and the Bushes knew each other well. In order to realize his ambitions for Enron, Lay needed access to loans and insurance from the World Bank, the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). In exchange for the great assistance President George H.W. Bush’s administration had given Enron, Enron and its executives “labored mightily” for Bush in 1992. Lay was named co-chairman of the Bush Sr. reelection committee as well as chairman of that summer’s Republican National Convention, to which Enron contributed $250,000.

As Bush Sr. was leaving office, Lay desperately wanted the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to exclude energy trading from CFTC oversight. Thanks to CFTC chairman Wendy Gramm, wife of Enron’s close ally Sen. Phil Gramm, a normally lengthy process was raced through the commission just before the Clinton inauguration. There are five seats on the CFTC, two of which were temporarily vacant; the vote in favor of Enron was 2-1. Shortly thereafter, Wendy Gramm resigned from the CFTC and, about a month later, became a member of the Enron board of directors. Her compensation was calculated by Public Citizen at between $915,000 and $1,853,000 for the period of 1993-2001.

In 1996, Ken Lay played a leading role in trying to get the GOP presidential nomination for Phil Gramm. Gov. George W. Bush also backed Gramm. In 1994, Richard Kinder, Enron’s president and chief operating officer, was Bush Jr.’s top Houston fundraiser. As soon as George W. was elected governor, he appointed Enron’s choice, Patrick Wood, to head the Texas Public Utility Commission. Wood was a vigorous supporter of deregulation of electric utilities.

Enron’s “friendliness” toward government agencies, domestic and foreign, paid off handsomely. Over a ten-year period, Enron was given $7.2 billion in publicly funded financing for 38 projects in 29 countries. Of that amount, U.S. agencies and development banks contributed $5.3 billion. Phillips writes:

In 1999 and 2000, Enron’s in-house lobbyists spent $3.4 million promoting a deregulation agenda in Congress, and the salaries of those registered came to nearly $1.6 million. At its peak, the company’s Washington office staff was over one hundred strong, including former aides to House majority leader Dick Armey and the wife of House majority whip Tom Delay. When this kind of money spoke, national and state legislators listened.

In 2000, Enron, Lay, and Enron’s Houston law firm, Vinson Elkins, were Bush Jr.’s biggest contributors. The Republican National Committee was not overlooked—it received $713,200 from Enron and its officers. It is alleged that half of Bush Jr.’s donors had close ties to Enron. And the scare in Florida was quashed by Enron’s business partner, James A. Baker III.

Needless to say, new appointments were in order after Inauguration Day. Lay, along with three other major Bush contributors from Texas, was named to the five-member Energy Department transition team. Vice President Dick Cheney was chosen to lead the administration’s energy-policy task force. Patrick Wood was appointed to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and soon after became its chairman. It seemed as if every one of Enron’s choices was appointed: Glenn L. McCullough, chairman of TVA; Donald Evans, secretary of commerce; Theodore Kassinger (formerly of Vinson Elkins), Commerce Department general counsel; and many others including Robert Zoellick, Thomas White, Lawrence Lindsay, Karl Rove, and Marc Racicot.

Yet, in spite of the best-laid plans of rats and men, Enron went under. According to Phillips:

While the comment made in June 2000 by Ken Lay that “no member of the Bush family has ever been on the Enron payroll” is almost certainly true, it is also irrelevant. Much larger amounts of money than ever changed hands in Teapot Dome reached the Bush family and their close political associates through multiple non-payroll routes: hard-dollar political campaign contributions, soft-dollar party contributions, consulting fees, joint investing agreements, funding for presidential libraries, lucrative speech payments, contributions to the costs of inaugurals, hypothesized Enron purchases of Bush-owned gas production, oil-well partnerships, and possibly even some of those off-the-books arrangements scattered around the world’s many tax havens.

There was a time when people in high places believed in avoiding even the appearance of impropriety. Phillips’ book suggests that the Bushes do not even know what propriety is.

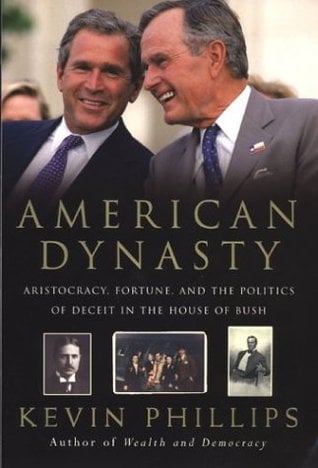

[American Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune and the Politics of Deceit in the House of Bush, by Kevin Phillips (New York: Viking Press) 397 pp., $25.95]

Leave a Reply