Herbert von Karajan’s sixty years of conducting have left their mark not only in the memories of generations of concertgoers, but in the holdings of record collectors all over the world. In addition to being the “General Music-Director of Europe,” Karajan is by far the best-selling serious musician who has ever recorded. Now that his extensive series of CD videos is being released, he has captured a new technology and managed to immortalize his visual image with his sound image, just as he had planned to do. Perhaps he should also have left us a hologram, as Sir Laurence Olivier did.

Karajan has gone further in reifying music, in dissolving his person into corporate entities, and in managing his career and life as a textbook example of public relations, than any other musician has ever done. He never explained satisfactorily just why the cash nexus, the glossy photos, the deluxe packaging, and the contrived mysteries were all necessary to share the joy of music with his public. Nor did he ever explain why he kept re-recording the same material, why he supplied so much “light music” (amiable trash, which he does better than anyone else), why he insisted on miscasting operatic roles so often, or why some of his work was cold, empty, slick, and—worst of all—boring.

In his conversations with Karajan, Richard Osborne isn’t about to upset the apfelwagen by pursuing any uncomfortable points. He adores the Master, and when you come to think about it, who can blame him? So much power, money, and control of musical shelf-space are united in the Karajan trademark; so much too of sheer talent, of shrewd patience, of unique sensitivity to music as sound rather than discourse. Though it is not a revisionist study like Joseph Horowitz’s Understanding Toscanini, Richard Osborne’s book is significant and revealing, and may be read for pleasure and instruction.

For make no mistake about it, Herbert von Karajan’s Wagnerian complacency was based on a rich background and a strong though individualistic sense of musicianship. He showed, as all great musicians do, an early talent and sense of vocation. He was imbued with a very Austrian sense of musical tradition, operatic performance, and Alpine yearnings. His combination of German romanticism and Buddhist detachment was anticipated by Schopenhauer— and Wagner.

Osborne spends considerable space on Karajan’s Nazi affiliations, claiming that his Party membership began as late as 1935 and was resigned in 1942, ten days after Karajan married his “partly Jewish” first wife. Though Osborne believes that Karajan suffered for his Nazi association, he seems to imply that the conductor suffered too for his Nazi dissociation, which rather evens the moral balance, or cancels it, or something.

Once on track, Karajan moved fast. By 1955, Furtwängler was dead, Toscanini was dying, and Karajan demanded and received lifetime leadership of the Berlin Philharmoniker. He had begun recording his best work—renditions of Bruckner, Strauss, Sibelius, and Italian opera, which music lovers still celebrate.

Richard Osborne’s colloquies with Karajan are directed by the interviewer’s knowledge—he knows what to ask. The conductor’s skill with Donizetti and Verdi, for instance, is attributed to powerful influences:

When Toscanini brought Lucia di Lammermoor to Vienna with the La Scala company, it was a revelation. I realized then that no music is vulgar unless the performance makes it so. . . . My training in Verdi’s Falstaff came from Toscanini. There wasn’t a rehearsal in either Vienna or Salzburg at which I wasn’t present. I think I heard about thirty. From Toscanini I learnt the phrasing, and the words—always with Italian singers, which was unheard of in Germany then. I don’t think I ever opened the score. It was so in my ears, I just knew it.

There can be no question that Karajan deserves great respect as a chef d’orchestre—his mastery was so deep that he talked in terms of breathing, heart rate, pulse, and yoga, in terms of energy, repose, and inner calm:

Many younger conductors are more exhausted after a concert than I am now. Nowadays Tristan und Isolde would not especially exhaust me. But the first time I conducted it I needed an ambulance to take me home!

I think that Karajan will be remembered for his best recordings, such as the pirated 1955 Berlin Lucia with Maria Callas, rather than for such wax fruit as his last recording, an Un hallo in maschera to be shunned. But even at the end, Herbert von Karajan was capable of such stunning work as his third recording of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony. That performance was taken on the road—I was one of those fortunate enough to hear the Wiener Philharmoniker play it in Carnegie Hall in February 1989. The critics raved and referred to that performance for a year as a benchmark, as they hadn’t done since Karajan crushed his opposition with a dream of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony some years before.

The Bruckner Eighth was incomparably the greatest live orchestral performance I have ever heard. The sight of Karajan struggling to walk, and then relaxing on the rostrum, was a demonstration of the passion that sometimes seemed a megalomania. So too does Richard Osborne’s Conversations articulate the context of Karajan’s self-absorption. Though uncritical, this book furnishes authentic insights into the life and career of a musical colossus.

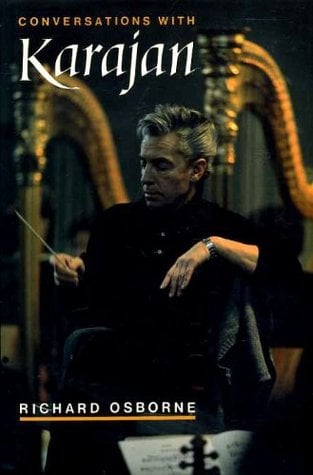

[Conversations with Von Karajan, by Richard Osborne (New York: Harper & Row) 157 pp., $22.50]

Leave a Reply