Early last October, there was an item in the national news that stirred some pity and some memories. “Minnesota Fats” (Rudolph Wanderone) had been taken into custody in Nashville after being found wandering the streets in a state of disorientation. A legend in his own mind, “Minnesota Fats” took his sobriquet from the fictional character in the movie The Hustler (1961), made from Walter Tevis’s novel of the same name. Before that he had been known as “New York Fats” and “Broadway Fats.” Old Fats had quite a gift of gab, even better than his pool game. But when Fats claimed that he had beaten the great Willie Mosconi, he got sued for $450,000 and challenged to a game for $20,000 in private cash. Fats didn’t respond. Then Mosconi challenged Fats to play for a hundred thousand, and waited in vain for a response to a registered letter. Six years later (February 14, 1978), Mosconi got his satisfaction in a televised confrontation glossed by the dulcet tones of Howard Cosell. It was no contest.

Well—who cares? I do. Everyone should acknowledge the beauty and excellence, the arete achieved through arduous years of competition. After all, Herbert Spencer did not say, as he is often supposed to have said, that “to play billiards well was a sign of an ill-spent youth.” He merely indicated that Charles Roupell had made the remark. In any case, it is one of those sayings that is exactly wrong—and Professor Harold Hill got that right in Meredith Willson’s The Music Man: “It helps develop horse sense, and a cool head, and a keen eye,” though even in that case, the invidious distinction that the professor was making (between three-rail billiards and pocket billiards) isn’t valid. No one did more to prove that than the author-subject of the present volume, who died at the age of 80 on October 16. Flags should have been flown at half-mast in observance of his passing, for Willie Mosconi was a national treasure.

Like Joe DiMaggio and Ben Hogan, Willie Mosconi was the personification of his sport, meticulously professional, an impeccable gentleman who played a ball game at a level of Olympian transcendence. Mere mortals who struggled with their own limitations and the laws of physics could only look on in wonder at someone who seemed to play not on green baize but upon an elevated Elysian field—on a hermetic plane of concentration that excluded even his opponents. He played against himself, and won often enough to immortalize his name.

It is a pleasure and a privilege, reading these pages, to hear a legend review the legends of his life. The legends are true. I mean, what can you do when you have to play Ralph Greenleaf (the greatest pool-shooter before Mosconi, world champion 13 times) at 8:00 on stage at the Strand Theater and you have tickets for Abie’s Irish Rose at 8:30? Easy. After Greenleaf breaks and plays a safe, you run off 125 nominated shots to win the game, as well as an assortment of trick shots to satisfy the audience—all in 17 minutes. When the curtain goes up across Times Square, you’re in your seat and ready to continue a pleasant evening.

That was in 1948. Of course, there was a predictable background to such skill and theatricality—Willie Mosconi was to the manner born, in Philadelphia in 1913 (the same year as Wanderone, whom he referred to as “Wanderphony”). His father owned a small pool hall from which the child was banned. He was soon standing on an apple crate, rolling potatoes with a broom handle upon a forbidden table. Moreover, Willie’s cousins were in vaudeville as “the Dancing Mosconis”—the combination of pocket billiards with show business seemed fated. Soon Willie, at the age of seven, played an exhibition match with Ralph Greenleaf himself—”The Child Prodigy versus the World Champion.” He would spend the next 25 years dethroning his model and nemesis.

The young Mosconi soon tired of the game. He returned to it at the beginning of the Depression only as a way to support his extended family. He was a shark but never a hustler, and from the beginning he took on the best at the highest level of structured competition. Such years took their toll: a stroke at the age of 43 retired Mosconi after 15 world championships, but it did not keep him away from the table. Nothing could keep him away from that platform where he once ran 526 balls before he tired; where he beat Willie Hoppe, the personification of three-rail billiards, at his own game; and where he did likewise to Rex Williams, the English snooker ace. Sometimes Willie used two tables, as for one of his most spectacular trick shots in which he knocked the cue ball into an are to another table where he sank six balls. Ho hum.

Willie’s Game tells it all, and gives us the history of pool in America as it goes. The book has two subtexts. One is Willie’s crusade to raise the level of the game (“pocket billiards” to him, never “pool”); the other is his struggle to win, his painful education in what it takes to beat the best. He had to learn the hard way never to let up on an opponent. As the billiards impresario Sylvester Entwhistle Livingston told him, “When you have the knife in, twist it.” Since that was against Willie’s nature, the struggle with others was a struggle with himself. Finally, Willie Mosconi learned the secret of the game: “But the best lesson of all . . . is a simple one: Don’t miss! If you don’t miss you don’t have to worry about anything else. I always kept that rule in mind when I shot, and I left many a son-of-a-bitch sitting in that chair a long while waiting to shoot again.”

Willie Mosconi did indeed raise the level of the game by the example of his performance and dapper, graceful demeanor. He was the last man in the world we could ever think of as “behind the eight ball” or “snookered.” His book is even more than entertainment and instruction, and for that some of the credit must go to Stanley Cohen. It is a worthy memorial to the Achilles of the felt and the Heifetz of the cue, and highly recommended to those enlightened souls who would rather read about the Billiard Congress of America than the United States Congress.

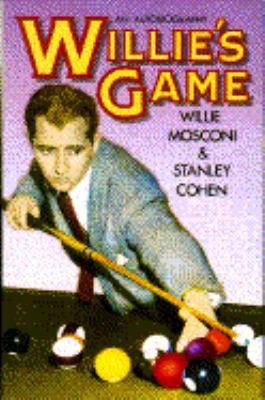

[Willie’s Game: An Autobiography, by Willie Mosconi & Stanley Cohen (New York: Macmillan) 256 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply