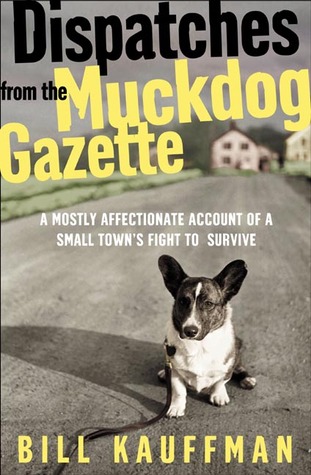

Dispatches From the Muckdog Gazette

by Bill Kauffman

New York: Henry Holt and Company; 207 pp., $22.00

A decade ago, a friend of mine was working for a prestigious law firm in Washington, D.C., which had decided to institute a “paperless” office. The process would take a couple of years; in the interim, to smooth the transition, every form had to be filled out three times—and each time in triplicate. (It was astonishing, my friend remarked, how many trees had to die in order to save paper.)

The process was overseen by a highly paid consultant, who demanded that the staff attend weekly meetings, which often ran most of the day. During a break from a particularly long and brutal session, my friend asked the consultant, whose business took him all across the country, about his travels.

“It must be hard to be on the road so much.”

“Well, I’ve gotten used to it. Of course, every city now pretty much looks the same; sometimes, I forget where I am. Today, every place looks like Cleveland.”

My friend, who had grown up on Long Island, began to commiserate, railing against the chain restaurants and big-box stores that are uprooting the last vestiges of local cultures and local economies. Pausing to catch his breath, he noticed the consultant looking at him, perplexed. “You don’t understand,” his interlocutor replied. “I like Cleveland.”

Embarrassed silence, as the gulf grows to infinite depth.

Every place like Cleveland: Not the real Cleveland, of course, the old industrial armpit of the Midwest that repeatedly managed the miraculous feats of turning Cuyahoga River water into fire and reducing the multitude of fish in Lake Erie to none, but the new, sanitized, Gap-and-Outback Steakhouse-and-Wal-Mart Cleveland, whose only tenuous connection to its past is the ABC/Disney Drew Carey Show, filmed on a Time-Warner lot in Burbank, California. In modern America, there are those who admire the “Cleveland success story” so much that they want to see it spread everywhere, and then there are the few of us who are willing to let Cleveland be Cleveland (even the new, “improved” Cleveland), as long as Cleveland is willing to let Rockford be Rockford and Batavia be Batavia.

Bill Kauffman is one of the latter. In his new book, Dispatches From the Muckdog Gazette, Kauffman provides a nonfiction account of the story he told in his earlier novel, Every Man a King, of returning to his hometown of Batavia, New York, after time spent in exile in Sodom-on-the-Potomac, where he was an aide to the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan. (Kauffman repeatedly expresses regret for having made the autobiographical hero of his novel sexually dysfunctional; methinks he doth protest too much.)

Readers who have enjoyed Kauffman’s writing in Chronicles will feel right at home in Dispatches From the Muckdog Gazette. Despite the subtitle—A Mostly Affectionate Account of a Small Town’s Fight to Survive—this book is not so much about Batavia as about the forces that are destroying small towns all across the United States and the all-too-feeble efforts of good and decent people to stem that destruction. Indeed, despite—or perhaps because of—the many nuggets of Batavia history that Kauffman offers, I found myself wanting to learn more, even though I have never been to the Burned-Over District of western New York, much less to Batavia itself. (Kauffman should consider writing a patriotic history of Batavia, if only to encourage others to do the same for their hometowns.)

In chronicling the (mis)fortunes of his hometown over the last half-century, Kauffman illustrates the foremost problem facing those who crave the stability that can only arise from a solid connection to the past: the inexorable march of progress. The defenders of the status quo are constrained by reality; the partisans of development and urban renewal are not. In order to win the battle, the progressives do not have to make good on their promises of a brighter future; by the time the pedestrian mall that replaced downtown fails or the new, modern courthouse crumbles to the ground, the visionaries have moved on to the project after next. Their moment of victory came when the farmland was annexed and rezoned commercial or when the wrecking ball first punched a whole in the side of the “cramped,” “antiquated” limestone courthouse (or, really, when they convinced a sufficient number of politicians that the century-old building was “cramped” and “antiquated”).

If Kauffman has a weakness, it is that he is too much of a dreamer; despite his Catholic upbringing, he wants to believe in the essential goodness of man (the same belief that animates the urban renewers he criticizes). When Wal-Mart came to town in 1992, Kauffman could see the writing on the wall. And yet, the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing:

My voice was as mute as the others in that silent night, unholy night. I suppose I am of the old New England school of Thoreau and Emerson in that I distrust political solutions and prefer individual revolutions of the soul. I sympathized with those townspeople who wished to keep Wal-Mart out. But instead of passing laws to compel behavior I would much rather that my neighbors choose to shop locally. They will only do so when Batavia becomes once more a city with its own flavor and fashions. Whether that day will come I do not know.

I don’t know either, but I do know this: By allowing Wal-Mart in, Batavia made it much less likely that such a day will ever dawn. In the rest of the chapter, Kauffman chronicles the casualties of Wal-Mart, ending with Batavia’s Finest Store, C.L. Carr Co., a family-owned department store downtown that, amazingly, managed to last almost a decade after Wal-Mart arrived, finally closing on July 31, 2001.

When Kauffman writes of “passing laws to compel behavior,” his libertarian roots show. Batavia, of course, would not have had to pass a new law to keep Wal-Mart out; in all likelihood, the city needed only to refuse to grant a zoning change or to issue a building permit. Wal-Mart, like all of the mammoth corporations that have colonized the far-flung corners of our continental empire, relies heavily on zoning changes, variances, special-use permits, and property- and sales-tax abatements to enable its continued expansion. This behavior is, as Wendell Berry (among others) has pointed out, a form of imperialism, no less insidious (and, in some ways, more so, if only because it’s being imposed on our fellow citizens) than Washington’s foreign adventurism, which Kauffman so adamantly opposes. If the evil Canucks sent an army across the border to occupy Batavia, would Kauffman refuse to resist, hoping instead that Batavians would choose to continue to pledge their allegiance to the Stars and Stripes rather than to the Maple Leaf? It would be naive (at best) to argue that economic choices are free while political choices are less so; once a corporation approaches monopoly status—and, throughout much of America, Wal-Mart has done more than just approach it—the “consumer” has no more freedom than does the voter in our essentially one-party system. Viewed this way, keeping Wal-Mart out of your hometown is a form of homeland security.

In the end, however, Kauffman’s weakness is also his greatest strength. If he overestimates the potential goodness of his fellow Batavians, it is because he can see a Batavia not urbanly renewed but reborn—rebuilt not on a sterile vision of endless progress but on the concrete reality of its past, warts and all.

Excoriating Walter D. Webdale, Kauff-man writes that the chief architect of Batavia’s urban renewal in the mid-1960’s

sneered that the city’s built landscape had nothing “uniquely Batavian. We have things typically American from all over this part of the country.” Nothing “uniquely Batavian”? As if the stone quarried, the wood hewn, the bricks laid, the tears and kisses and lives passed within the hundreds of homes and small shops on Webdale’s hit list were abstract nothings.

Forgive them, Lord—though they knew very well what they were doing.

If Rockford and Batavia are not to become Cleveland, then, against the homogenizing vision of the partisans of progress, we must erect an imaginative bulwark that will appeal more strongly to Rockfordians and Batavians. In Dispatches From the Muckdog Gazette, Bill Kauffman reanimates the true soul of Batavia and, in the process, shows us the way back home.

Leave a Reply