“Man was wade of social earth.”

—R.W. Emerson

Ever since Frederika MacDonald published her massive two-volume work, Jean-Jacques Rousseau: A New Study in Criticism (1905), scholars favorably disposed toward Rousseau have pursued the difficult task of rehabilitating him from the “audacious historical fraud” perpetuated by Frederic- Melchior Grimm, Denis Diderot, and Mme. d’Epinay. On the authority of Grimm’s malicious Correspondance Littéraire (1812), and Mme. d’Epinay’s deliberately doctored Memoirs (1818), during the entire 19th century and well into the 20th, the public image of Rousseau was that of an emotionally unstable and repulsive personality and a moral cretin. Voltaire’s intense contempt for Rousseau, generally attributed to envy, together with harsh personal criticism by other philosophes, contributed to this wholly negative portrait of Rousseau. Also, even before the conspiracies to defame him became public, his Confessions provided much added credence among traditional conservatives to the common belief that his psyche was deranged. The long tradition, which stretched from Samuel Johnson and Edmund Burke to Irving Babbitt, confirmed the widely held conviction that there were reptiles swarming in Rousseau’s Eden-like image of primitive, idyllic nature.

Contemporary biographers such as Jean Guéhenno, Lester Crocker, Ronald Grimsley, and Jean Starobinski were often compelled to wrestle more with Rousseau’s troubled psyche than with the empirical facts of his life. They have often exonerated him from some of the most negative mythological strictures made against him, but sometimes unwittingly they have also confirmed much that his Enlightenment and conservative critics have contended. An added difficulty was created by biographical scholars in the history of ideas, who often carried the negative portrait of Rousseau’s character and personality into their exposition of his philosophical ideas on politics, society, religion, education, and human nature. Frequently they condemned his philosophy as false and pernicious because they perceived it as a mere extension of his unbalanced mind and sensibility. In her apologia of Rousseau, MacDonald committed the same error in reverse: “Rousseau’s private life was an example, in an artificial age, of sincerity, independence, simplicity, and disinterested devotion to great principles; and . . . his virtuous character and impressive personality lent authority to his writings.” Recently, this line of reasoning was carried to its reductio ad absurdum by Christopher Kelly in Rousseau’s Exemplary Life (1987). Although MacDonald’s sources for the empirical facts of that life were severely limited, she claimed that all scholars who deal with the biographical facts and writings, and avoid the pejorative myths, admire Rousseau, and that only those who ignore or despise historical facts calumniate him and his philosophy, and cast both to the dogs.

Maurice Cranston’s biography, utilizing manuscript sources far beyond those employed by MacDonald and other biographers, is perhaps best perceived as a judicious, prudent, empirically objective, and thoroughly poised scholarly work in the long tradition begun by MacDonald of rehabilitating Rousseau. His first volume, Jean- Jacques: The Early Life and Work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1983), covered the formative years of his subject’s life up to age 42, from 1712 to 1754. It was almost universally acclaimed as an outstanding achievement in biography, particularly for its perceptive insights into Rousseau’s life and in its judicious but brief treatment of such early important works as Discours sur les sciences et les arts and Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité. Cranston based his work on the magnificent edition of Rousseau’s correspondence, edited by the late Professor Ralph Leigh, and on original manuscript sources in Geneva, Neuchatel, Paris, Savoy, Turin, Oxford, and many other research centers. His stated objective was to reverse the habit of writing biographies of Rousseau based upon published books and “printed folklore.” His basic method was to deal as completely as possible exclusively with empirical and’ historical facts, to be wholly descriptive, and to omit emotive responses and normative moral or intellectual judgments regarding Rousseau’s character, temperament, philosophy, and historical significance by setting forth the evidence in a straightforward chronological manner. To this end he correlated the facts of his subject’s life and works with the account presented in the Confessions, noting where Rousseau’s statements were confirmed, qualified, or contradicted.

Cranston extends his “Lockean biography” in volume two, and utilizes the same manuscript sources and neutral empirical method so evident in the first volume. He covers the vital years 1754-1762, when Rousseau wrote and published such important works as Lettre à m. d’Alernbert, Julie ou La nouvelle Héloïse, Emile, and Contrat social. Cranston’s empirical approach to Rousseau’s life and works has the great virtues, and also the inevitable limitations, of all positivist descriptive scholarship in the humanities.

Its greatest strength lies in the firm foundation of its concrete historical facts. Perhaps its chief negative merit is that it almost wholly avoids every kind of subjective, doctrinaire, or ideological basis, theory, or interpretation for or against Rousseau. Judgments are left up to each reader. Cranston is about as far removed as any biographer can be from the solipsistic anarchy of a reductionist account of Rousseau’s life and philosophy. Beyond noting some intellectual inconsistencies, he refuses to pass judgment on Rousseau, so that although he clearly admires much about Rousseau, his subject is pictured largely without blame or praise. Cranston is too careful a scholar to make imprudently dubious correlations between Rousseau’s autobiography and his politics, so that unlike Christopher Kelly’s Rousseau’s Exemplary Life he avoids the crude error of reading Rousseau’s Confessions as political theory or practice. The whole spirit of his study differs in every way both from past pejorative scholarly commentaries and from the eulogistic encomium that characterizes Kelly’s biographical-political panegyric.

Only once does Cranston digress significantly from his empirical-descriptive method. The great knowledge, understanding, and skills he acquired during his long career as a distinguished teacher of political philosophy at the London School of Economics and elsewhere are very evident in the chapter “Two Social Contracts,” where in some detail he analyzes Rousseau’s Social Contract. He compares Rousseau and Hobbes for similarities and differences regarding the fictional precivil “state of nature,” the hypothetical primitive state from which men supposedly formed the original “social contract.” As compared to the social compacts of the Old Testament in the Decalogue and the covenant of 1620 of the Puritan colonists of New England, Cranston writes: “Rousseau’s social contracts are less specifically historical events.” In truth, Rousseau’s social contracts are not historical at all, but purely speculative fictions. Rousseau himself admitted that men know nothing of the state of nature, not even whether such a state ever existed. He then proceeds to argue as though it had an actual historical existence, and Cranston, like all scholars favorably disposed to Rousseau, gives serious credence to his hypothetical premises and endows the precivil state of nature with historical significance. In contrast, Edmund Burke refused to accept Rousseau’s fiction as a historical fact, or even as a metaphorical hypothesis, and held that it is necessary to draw a veil over the unknown prehistorical origins of government. Burke held that it is preposterous to ignore totally the known actual history and culture of Europe, from the ancient classical world of Greece and Rome, and what he called “the Christian commonwealth of Europe,” and to substitute for the empirical facts of known history the purely imaginary, speculative fictions of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau.

As Orestes Brownson noted in 1865 in The American Republic, it is an empirical fact that no nation ever came into existence out of a social contract formed by men living in a state of nature. All such social contract theories, Brownson argued, are false to historical fact, false to human nature, and therefore false to any valid political philosophy. The precivil “state of nature” is best dismissed as a wild figment of speculative imagination, a mere fictional abstraction that has no existence in the world of reality. The total historical inheritance of Western civilization, and not any ideological speculative theory, was the only safe and sane source for political and social philosophy.

Cranston admits that there is no “instinct” in human nature to form or support Rousseau’s supposed social contract. Rousseau’s own belief in the radical, self-contained individualism of primitive man also militates against the possibility of forming such a social contract. In total contrast to Aristotle and Burke, Rousseau denied that civil society and its institutions are “natural” to man; he believed that organized society is “artificial.” He would have wholly rejected Burke’s aphorism, “Art is man’s nature,” and its derivative argument that “the state of civil society . . . is a state of nature—and much more truly so than a savage and incoherent mode of life.” But to understand Rousseau’s Social Contract it is necessary to see it in the light of his earlier work, the Discourse on Inequality.

Rousseau had made it plain that he conceived the original “social contract” as a colossal fraud, because the division of labor in primitive society had led to inequities through private property, and to a rigid class structure that perpetuated injustice and conflicts between the rich and the poor. Inequality in economic and social conditions was to Rousseau the source of every evil. He argued that society corrupts men by destroying the amour de soi-même found in “nature,” converting it into amour-propre, the desire in society to dominate others. Thus he claimed that civil society, not weaknesses inherent in human nature, causes such vices as pride, envy, avarice, vanity, etc. He assumed that the economic pie could not be enlarged, so that the wealth of the rich was to him the cause of the poverty of the poor. From this assumption he wrote to Mme. de Francueil and defended his decision, beginning in 1746, to put his five illegitimate children in an orphanage at birth: “The earth produces enough for everybody; it is the life-style of the rich, it is your life-style which robs my children of bread.” Fifteen years later, in 1761, when Rousseau was sick and thought he was about to die, his troubled conscience caused him to have a search made in the foundling hospital records in Paris, but nothing was discovered regarding his children. Rousseau’s social contract with his own children was indeed a colossal fraud.

Cranston notes that Rousseau’s Social Contract “was to prove far more explosive, far more subversive of the Ancien Regime than anything Voltaire wrote.” This is quite true. Rousseau’s revolutionary political treatise presents the second of what Cranston calls “two social contracts.” It was written out of Rousseau’s belief that he was uniquely chosen by God or Nature to redeem humanity from the injustices and slavery of the “original” social contract that had been perverted by rulers throughout history. To the pure all things are poor. The important Calvinist residue in Rousseau’s conscience and spirit reveals itself in his conviction that compared with the unregenerate mass of humanity he is one of God’s elect, not in religion but in politics, and that he possesses from his self-generated inner light unique political revelations that are vital for the salvation of mankind. Cranston notes the explicit substantive similarities in political ideas between Rousseau, Hobbes, and Machiavelli, but mentions nothing of the more important assumed Calvinist psychology in his Social Contract.

With fine analytical skill Cranston explicates Rousseau’s Social Contract and gives due consideration to some of the chief weaknesses in its thesis. He is not troubled by Rousseau’s idea that the state can force a man to be free, and he denies that this idea can be equated with modern totalitarianism, as claimed by J.L. Talmon, Lester Crocker, and others. Yet recent scholarship on Rousseau by Norman Hampson, James Miller, and especially Carol Blum strengthens the interpretation of Talmon and Crocker. Cranston is well aware of Rousseau’s great’ difficulty (Jacques Maritain said the impossibility) in attempting to harmonize the various particular interests, and individual wills and “rights” of private citizens and corporate bodies, with his “General Will” or volonté générale, which determines sovereignty in the national community. Among Rousseau scholars the range of interpretations of what he meant by volonté générale is almost as broad as the number of scholars, and Cranston adds nothing original to our understanding of this grand, abstract concept. Like Hobbes, Rousseau reduced the Church to a department of the state and identified religion with patriotism. Like practically all Rousseau scholars, Cranston is acutely embarrassed by what he calls Rousseau’s “most astonishing chapter” on civil religion. The man of feeling explicitly advocates religious persecution, and his doctrine is very similar to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy adopted by the Jacobins during the French Revolution in July 1790. Rousseau’s theory, like the practice of the Jacobins, banishes from the nation anyone who rejects the civic religious patriotism of the new order, and sanctions “punishment by death” for any citizen who acts as if he does not believe in its patriotic articles of faith.

Although Cranston makes as good a positive case for Rousseau’s political theory as any scholar since C.E. Vaughan, in the final analysis he comes to his conclusions by minimizing the great difficulties embedded in Rousseau’s original conditional premises and in his abstractions, ambiguities, paradoxes, and contradictions. Early in the 20th century, Gustav Lanson said that Rousseau is rife with contradictions and that his most sophisticated and clever scholars have not been able to harmonize his thought. This still appears to be true. Cranston achieves a certain degree of unity by ignoring the more dubious elements in Rousseau’s theory. For example, he says nothing about the chief function of Rousseau’s lawgiver, the “legislator” who, like Lenin, would change human nature by annihilating each individual’s “natural resources” in order to form the new character of a good citizen in Rousseau’s republic of virtue. The model of his republic is an idealized image of Calvin’s Geneva mated with the discipline of ancient Sparta. It is generally supposed that in his Social Contract Rousseau regarded himself as the true lawgiver to his proposed regenerated social order. However that may be in abstract theory, in concrete practice during the French Revolution the Abbe Sieyes, Robespierre, and Marat each separately assumed that he was Rousseau’s lawgiver for the regenerated social order of revolutionary France. But of course, in practice, the final true lawgiver of revolutionary France was Napoleon Bonaparte.

In a way, Cranston recognizes that Rousseau’s aesthetic and moral sensibility is even more important than his political one. He notes that in 1761, when Rousseau published Julie, the novel “transformed Rousseau from a celebrated author into the object of a cult. . . . Julie . . . established him as a dominant figure in European culture. It changed the ways in which people thought and felt and acted.” Precisely so, which is why between 1761 and 1780, 50 books in France imitated Julie and 72 editions of Rousseau’s novel appeared before 1800. “Sensibility” is of paramount importance in the 18th-century, and although Rousseau did not originate the ethics of feeling, his vital role in spreading it throughout Europe is a necessary part of his intellectual and moral biography. Cranston’s three brief sentences on Rousseau’s novel are hardly an adequate treatment of this sensibility. Undoubtedly, a “Lockean biography” cannot handle such a complex psychological subject, which would carry us into the intellectual and moral domain in the history of ideas during the 18th century.

Other important subjects involving both Rousseau’s private life and social theories are also omitted because they lie outside of Cranston’s self-imposed empirical-rational method. Indeed, everything that makes Rousseau controversial as a person and thinker is left unresolved. For example, the enormous gap remains fixed between how Rousseau perceived himself and how he is viewed by his admirers, in contrast to how his enemies saw him in his own time, and critics up to the present have understood him. Perhaps no writer surpassed Rousseau in the art of converting good friends into lifelong bitter enemies. While they were still friends he wrote to Grimm: “As for kindnesses, I do not like them, I do not want them, and I do not feel grateful to those who force me to accept them.” Rousseau never distinguished between patronage and benevolent friendship, and therefore treated gratitude for favors not as a social virtue but as a moral vice. He was quite ambivalent in accepting, yet resenting, generous assistance from Mme. d’Epinay and others, while indignantly scorning smaller gifts from them. Such behavior creates problems for his defenders, who perceive him as a man of integrity, independence, and firm adherence to principle. It also provides an opening for his critics, who find at the core of his exalted, abstract moralism a bleak epicurean and self-righteous nihilism and vanity: in short, a psychotic personality. Which view of Rousseau is valid? Empirical biographical facts alone do not answer that vital question.

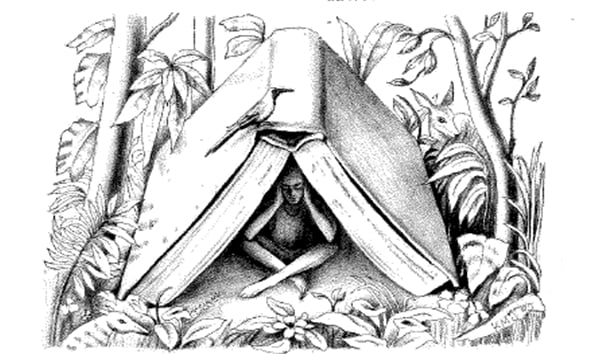

One final ironic touch is worth noting. During the 18th and 19th centuries, critics of Rousseau often accused him of being a “primitivist.” Two of his early 20th-century defenders, Ernest Hunter Wright and Arthur O. Lovejoy, among others, defended Rousseau from this charge. Cranston calls his biography The Noble Savage, which infers that “primitivism” is no longer perceived as a pejorative term. But Rousseau was not so much a primitive noble savage as he was a hermit living occasionally a rural life within the polished institutions of European civilization. He strongly resented Diderot’s remark that only an evil man needed to live apart from society, because he regarded himself as the embodiment of his doctrine that man is by nature good, and that only organized society is evil.

[The Noble Savage: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754-1762, by Maurice Cranston (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 599 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply