“I never desire to converse with a man who has

written more than he has read.”

—Samuel Johnson

The late Louis Lomax, columnist and television personality, had delivered a lecture at Ferris State College, Michigan, when there arose in the audience a large, militant, black activist. “Lomax,” said this challenger, grimly, “do you call yourself black?”

“Do you want that with a small b or a capital B?” Lomax inquired, shaking his head.

“Well, Lomax, do you call yourself Afro-American?”

“No, brother.”

“Then do you call yourself Negro?”

“No.”

“You mean you call yourself colored?”

“No.”

“Then what do you call yourself?”

“Louis Lomax.”

Mr. Ralph Ellison, although for the most part he writes about the Negro (the term he employs), also does not need to be classified according to pigmentation or ideological fad: He stands in his own right as a man of letters. A gentleman of presence, he is one of the more temperate and tolerant writers of our time, urbane and courageous. He wrote a first novel that presumably will be his last novel: Invisible Man (1952), at once realistic and fantastic, moving and convincing, the best American fiction of the past several decades. Like Santayana, Ellison can rest with a single novel and still be numbered always among our principal authors of fiction.

One volume of essays and occasional pieces, Shadow and Act, followed Invisible Man. This new collection, Going to the Territory, is the only book Mr. Ellison has given us since then. He could have made a great deal of money and obtained a great deal of attention by churning out magazine articles and sensational novels; but Ralph Ellison is a modest and honest man of letters, endowed with dignity: a very rare bird in this age.

In “The Little Man at Chehaw Station,” the first essay in this collection, Ellison touches upon artistic standards and the invisible American critic, lurking behind the stove in the railway station, so to speak. That Little Man “serves as a metaphor for those individuals we sometimes meet whose refinement of sensibility is inadequately explained by family background, formal education, or social status. These individuals seem to have been sensitized by some obscure force that issues undetected from the chromatic scale of American social hierarchy. . . . In this, heredity doubtless plays an important role, but whatever that role may be, it would appear that culturally and environmentally, such individuals are products of errant but sympathetic vibrations set up by the tension between America’s social mobility, its universal education, and its relative freedom of cultural information.”

Here Mr. Ellison is not referring to himself, but those sentences might readily be applied to him. As a boy, he came from a Negro neighborhood in Oklahoma to study music at Tuskegee Institute, and there picked up a copy of The Waste Land—Eliot’s notes thereto led him to other books; and so, by chance or providence, he became in time a man of letters. The influence of T.S. Eliot may be discerned in him still.

As I wrote of Ellison 17 years ago, “Mr. Ellison has vision, and he can write, and very early he fought free of ideology. He does not fall into the delusion, even in its inverted sense of ‘belligerent negritude,’ that there is something wrong about being colored or being poor. . . . He does not mean to whitewash the colored man, or to convert all the poor into dully affluent suburbanites. He is endowed with the tragic sense of life.”

Ellison is thoroughly American, and content to be. In Going to the Territory, as in his earlier volume of essays, there occur only glancing references to any British or European authors, except so far as Eliot and Henry James may be considered quasi-British. (Eliot, who classified himself as an American writer even after he became a British subject, remarked that the worst form of expatriation for an American writer was residence in New York City—as indeed the naive boy of Invisible Man discovers.) Nor does he mention anyone who wrote before the 19th century. He grew famous by writing about what he knew best: the experiences of a well-intentioned young Negro seeking to survive in the antagonist world. In part because of editors’ and colleges’ requests, doubtless, most of his speeches and essays have been related to questions of the Negro in the United States.

But no one ought to fancy that his talents are confined to writing about racial problems and Negroes’ successes and difficulties. Two of the essays in this volume, “Society, Morality, and the Novel” and “The Novel as a Function of American Democracy,” scarcely mention anything about color or subculture; and they are able, forthright successes in criticism, independent and persuasive. In the one he drubs Lionel Trilling; in the other he affirms the moral function and duty of the novelist.

“The state of our novel is not so healthy at the moment,” Ellison writes as he concludes “The Novel as a Function of American Democracy.” “Instead of aspiring to project a vision of the complexity, the diversity of the total experience, the novelist loses faith and falls back upon something which is called ‘black comedy,’ which is neither black nor comic. It is a cry of despair. Talent and technique are there; artistic competence is there; but a certain necessary faith in human possibility before the next unknown is not there. I speak from my own sense of the dilemma, and my own sense of what people who work in my form owe to those who would read us, and read us seriously, and who are willing to pay us the respect of lending their imaginations to ours.”

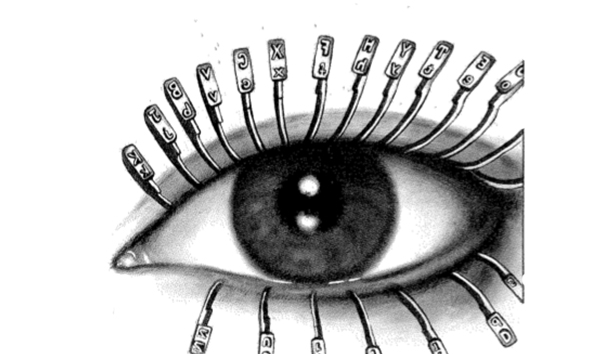

It will be gathered that Ralph Ellison is a writer possessed of moral imagination who knows, with Irving Babbitt and T.S. Eliot, that the end of great literature is ethical. In the literature of what Eliot called the diabolical imagination, he will not traffic. Americans, more than any other people, need novels to “produce imaginative models of the total society,” he argues. “If there had been more novelists with the courage of Mark Twain or James or Hemingway, we would not be in the moral confusion in which we find ourselves today. If we do not know good from bad, cowardice from heroism, the marvelous from the mundane and the banal, then we don’t know who we are. It is a terrible thing to sit in a room with a typewriter and dream, and to tell the truth by telling effective lies; but this seems to be what many novelists opt for.”

Amen to that. Once upon a time Mr. Ellison and this reviewer shared a television broadcast, arranged by Harvard people, about the state of education in America; our views were not dissimilar.

Months later, a Harvard quarterly journal prepared to publish our remarks. There was sent to me, together with proofs, an editorial note meant to be preface to the discussion, beginning with these words:

“Ralph Ellison and Russell Amos Kirk, two of America’s leading black writers . . . “

I sent back a note thanking the editors for the compliment but confessing that I possessed no claim to such a distinction, unless some quantity of Redskin blood in my wife’s veins would qualify me. What Mr. Ellison and I happen to share in the American melting pot (a vessel approved by Ralph Ellison) is not the accident of color, but certain convictions about humane letters.

[Going to the Territory, by Ralph Ellison (New York: Random House) $19.95]

Leave a Reply