“All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is

that good men do nothing.”

—Edmund Burke

There is a photograph of Rebecca West taken shortly before her death: she sits in a throne-like armchair looking slightly off camera. One of her hands rests on the carved handle, the other is in her lap. Her hair is respectably gray and her necklace and her rings, without any doubt, come from the right store. She has everything: money, self-confidence, knowledge.

It is her answer to the hate-mail she has been receiving all her life and for having started out as Cicely Fairfield, unsuccessful actress, London’s instant literary celebrity, and unwed mother. In 1983 she died at the age of 90, a Dame of the British Empire, after lighting the age with her intelligence and vivacity.

Her newest official biographer, Victoria Glendenning, attempts to defend West as a frail human being who needs our understanding. If Dame Rebecca tried to achieve, through Mrs. Glendenning, what she had often been accused of wanting while still alive—”a good posthumous press”—the result is not a complete victory for the defense.

By choosing to follow the middle road between her respect for both Rebecca West and her accusers, the alleged defender has unwittingly joined the side of those who saw in the British author, dead as well as alive, a threat to their cherished notions, nourished vanities, and vested interests.

As West herself once wrote, “as in the case of divine revelation, and also in case of tea-leaf reading, there is no concern here [in biographies] with sheer brute evidence.” Victoria Glendenning quotes this statement only to forget it. Instead, in her account of West’s rise in the intellectual and social circles, she emphasizes the rise itself as a social phenomenon. Glendenning furnishes an exhaustive list of Rebecca West’s ancestors (not forgetting possible royal connections); she gives us detailed descriptions of her various habitations, furniture, French paintings, number and type of wine bottles in her cellar; we are titillated with a chart of West’s love affairs, including an explanation of why her most famous lover, H.G. Wells, failed to take “usual precautions” and made her pregnant during their second encounter. We read of a spat between West and Virginia Woolf, and a spirited defense of West’s love for too much lobster and too many hats.

The reviewers have sopped all this up, each vying to add to the treasury of “facts.” The public was informed of the occasion when West was taken raving from the “Ritz” by her husband and a waiter; the uncontrollable temper, it was insinuated, was not reserved only for her personal life: it tainted all her achievements, while her fiction was nothing but a constant rewriting of her early life.

Rebecca West’s detractors came out swinging: Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, which brought her fame, is only an “artless exercise in self-indulgence” crowded with confusing statements and twisted reality (Rebecca West continued aiding Serbs well after Winston Churchill handed their homeland to Tito); she was accused of being a “paranoid anti-Communist” (during the heyday of Burgess, McLean, Blunt, and others) who was as obsessive in her black-and-white view of the world as she was in her personal relationships.

In West’s postmortem, reality and truth have as much weight as any other opinion, and she has been dragged over the coals by all and sundry, even by her only son, who had noted cynically that his mother thought “life could be improved by editing.” (For a neglected child, Anthony West had little rancor for his father, H.G. Wells, who conveniently stayed away from him all his life.)

Though she was equally celebrated for her fiction, that part of her oeuvre is of less importance. Her novels are uneven and not so much works of art as explorations of an art form. Her first novel. The Judge, leaves the reader wondering whether the exotic atmosphere and anatomic treatment of characters are a coincidence, a fad, or an attempt by a young artist to develop a recognizable hand. In her best fiction, The Fountain Overflows trilogy (in a way foreshadowing Ayn Rand), a family’s story comes alive, but West is definitely not at her best in fiction: she is much stronger than any of her characters. She attains her true stature by combining the assumed, the glimpsed, or the desired with the real—as in her best work. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon—confusing most critics along the way.

An imaginative journey through the mountains and the valleys of the Balkans, with ruminations upon Bogomil sanctuaries and Roman ruins. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is full of unforgettable people—a nameless Montenegrin woman near an incredibly blue river, distraught over her wasted life, trying to make sense of it; the young soldiers guarding a military cemetery on the Kaymakchalan, afraid of the dead soldiers calling for their mothers; an officer grieving beyond human (Western) limits on a hilltop above Sarajevo (while at the same time maintaining his composure for the sake of his uniform)—who were also seen by many critics as chance destinies of nameless beings, entirely divorced from our common condition.

To people in the Balkans, the exotic places West mentions are the familiar countryside in which they lead their everyday lives. By elevating what she saw to a higher level of myth, she sketched a parable of life beset by the forces of evil.

For feminists, leftists, and others it was easiest to identify this work as a sort of science-fiction travelogue—with its irrelevant images of snow burying Croatia in April, covering the fields and the road leading the author and her companions to a disastrous dinner. West’s tale of how a Hungarian king and his queen found refuge from Asiatic hordes on an Adriatic Island, and were saved only by several feet of sea-channel and the news of the Great Khan’s death, has, naturally, no bearing upon anything we know. Removed in space as in time, nothing, of course, is relevant, because nothing is coded, and the clef fails.

Rebecca West’s Manichean world of ultimate evil arraigned against blemishless virtue, brilliant as it is unbearable, is her only tool. But the evil is not to blame for being true to itself; the sacrifice of a black lamb on the Sheep’s Field in Macedonia by nominal followers of a monotheistic religion is for her a stark illustration of what “good” people are doing all the time, to save themselves. West’s sickening description of the sacrificial stone, slimy with the blood of butchered sheep, with barefooted Moslem dervishes (probably good men all) extolling their acts of Molochian faith, came out in 1941, at a time when the Yugoslavs joined Poles and Czechs as victims sacrificed to appease the powers of destruction. (All of it as if happening on another planet, at a mythical time—the rite of mollifying the “idiotic god.”) In our minds. West says, we have distilled the Choice into the impossible alternative of being either the victims or the butchers.

Every August, thousands of peaceniks paint themselves black and gray and prostrate themselves on the streets of major Western cities, eager to die in innocence. They, wrote West, probably see themselves as noble as Serbian Prince Lazar, who chose to die on the battlefield of Kosovo, in 1389, rather than live, in anything else than beatitude. The Poem of the Grey Falcon, which Dame West quotes in its crucial part, sings of Prophet Elijah disguised as the gray falcon, coming down to Prince Lazar, on the eve of the Serbian defeat with the offer of a choice between the heavenly and the earthly kingdom. The Turks, sings the falcon, will lose if Lazar chooses to live and win, but the Serbian kingdom will be only temporal, earthly, mortal, and virtueless . . . On the other hand, a defeat will transform the Serbs into a heavenly host, alive forever, to defend what is worth defending . . . Few foreigners have ever felt the Serbian “epic of defeat” as Rebecca West; few have spurned it as vehemently as she, with greater love for the living, real, flawed Serbs.

It is said among the Serbs that Prince Lazar lost his battle because of another famous Balkan ingredient—treason. Wanting either to settle a score or hoping to gain from the overall defeat of his race, Lazar’s vassal Vuk Brankovic arrived conveniently late to commit his forces in the decisive Battle of Kosovo.

But Rebecca West didn’t have to go back to the mythical Balkan world, in search for answers. In the post-World War II years the examples of treason were many and the need for response, in her view, more than urgent.

“Once a traitor comes to court, or under the notice of Parliament,” she wrote, “all that should interest the lawyers or the ministers concerned is whether he has been exercising his profession or not and who has been helping him. If inquiry is made into his politics and his morality much will be said, probably untrue, which will divert attention of the community from the real threat by the new traitor.”

In the Western societies’ refusal to deal with the fact and the meaning of treason, the case of William Jones, “Lord Haw-Haw” (covered in West’s book The Meaning of Treason), was a significant event: “Haw-Haw” was the last Western traitor sentenced to death (in 1946, for collaboration with the Nazis). At that time, no one but a few lonely voices protested against his punishment. The cases of such postwar spies, as Alan May Nunn, the Rosenbergs, Klaus Fuchs, Burgess and McLean proved, however, much different. The Western public saw the new breed of traitors not for what they were, but as refugees from “the vulgar district in the world of fancy.” After the images of the war started fading, the hunger for heroes had to be sated by what was at hand, and it was Andre Gide who wrote, “To me a worst instinct has always seemed sincere.” Simple, straightforward heroism was made to seem passé. As West put it, simple heroism has something “dawdy about it, while treason has certain style, a sort of elegance, or, as the vulgar say, ‘sophistication.’ ” In this inverted world. West went on to say, “people who practice the virtues are judged as if they have struck the sort of a false attitude which betrays the incapacity for art, while the people who practice vices are judged as if they have shown the subtle rightness of gesture which is the sign of a born artist.”

This cynical inversion of values is what constitutes the ruling morality of the “Eastern Bloc,” which, like any lethal disease, refuses to be contained by frontiers and geographic barriers. Though lacking the firsthand experience of someone who has lived in the Communist East, Rebecca West managed to detect its echoes in her own world, and she tried to fight it, giving it the proper name it deserved.

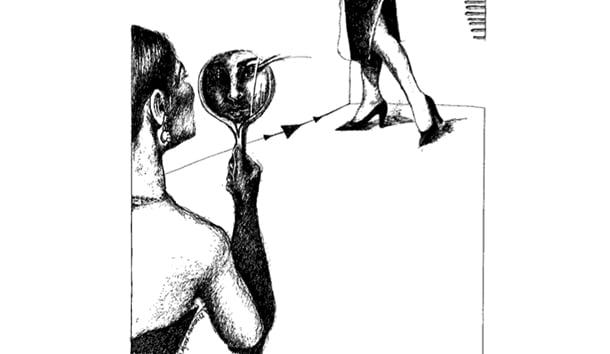

Speaking in conclusion not of the traitors’ but of our own morality, Rebecca West does not propose a police state which could handle the threat much better than the weak democracies. She places her hope upon the human species—on our ability for “tightrope walking.”

West had more than her share of flaws, but her personal and artistic failings are only used as convenient weapons by critics who cannot say that they really hate her for her virtues. The more distant in time our writers are, the better off we, their readers. Very few among us know and care that Giacomo Leopardi was a hunchback who hardly ever left his study, or that Dante Alighieri switched his political allegiance almost daily. Or that, besides having at least two illegitimate children, Francesco Petrarca, the master of the verses of pure love, returned to Christianity at the end of his life, just in case there was a God. Or that Oscar Wilde lived scandalously, though he wrote like an angel. Or that Dostoevski was a profligate and a gambler. Instead of denying the great their claim to greatness for not being the purest among the pure, it would be more just for us to say they were often great despite themselves. Few of them deserve praise for what they did, and even fewer for what they were.

And though we do not have to rediscover who Rebecca West was, we certainly cannot fail, in her case, to rediscover how often art becomes confused with politics. It is not only because artists themselves cannot refrain from meddling in worldly affairs; it is because they quite often have to surround themselves with followers and defenders, if they are to survive.

“Sanza avere armi proprie nessun principe e securo,” as Niccolo Machiavelli observed centuries ago. He himself was unjustly accused of ruthlessness and amorality in the centuries to come, for having honestly explored what the rulers of his (and other) times had to be and do to rule, without pretending they were just like the “friendly folks next door.” Machiavelli, however, should have directed his advice at writers, too. As for Dame Rebecca West, she, like the world she stood for, has yet to find the right defenders, somewhat more aware of what they are defending, and why.

[Rebecca West: A Life, by Victoria Glendenning, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson]

Leave a Reply