“Fame is a calamity.”

—Turkish Proverb

The face is familiar, but not the gray hair. To some few, it may be so from Our Gang shorts from the late 30’s and early 40’s, known by the moniker of Mickey Gubitosi. To others, it is the face of Bobby Blake of “Red Ryder” westerns and Humoresque (1947) and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). To many, it is Robert Blake of Baretta on 70’s television, in some episodes of which he disguised himself as a swishy character singing “Strangers in the Night”; but to most, it is familiar as that of the haunted killer Perry Smith, the lead in Richard Brooks’ film In Cold Blood (1967), the role of a lifetime. If I am at all informed, Robert Blake’s alibi for the alleged murder of his wife is that he could not have shot her because he had to go back into the restaurant to get his gun. Perhaps the author of In Cold Blood, with his celebrated powers of empathy, could have understood that one; which thought brings us to the matters at hand, for Truman Capote does come to mind these days, and for more reasons than those associated with Robert Blake. And the face of Capote, also, was a much-photographed face.

The dreary publishing scene is so lacking in spark that a longing glance in search of some wisp of inscribed stylishness must necessarily be a wistful and retrospective one. Yes, these books kind of take you back, but the tug of nostalgia contains within it a compensatory repulsion. To begin with, Reynolds Price’s affected Introduction to the stories is nearly repellent enough to make me snap the book shut: “America has never been a land of readers, not of what’s called literary fiction in any case.” Earth to Professor Price: How are things in outer space, and how do you think Truman Capote made all that money? (Because look here, Mr. Professor, it would have been pretty hard for Truman Capote to make a living by writing, much less get rich, if there had been no readers of those estimable fictions of his.) But, dispensing with nonsense, we might yet want to make some sense of Truman Capote’s literary remains, in their short manifestation at least, and to come to terms with the parabola of his career as well as the attraction that still has a certain spooky glow.

Writing fiction professionally is a treacherous undertaking. If the tests of merit and even success are surmounted, the problems only accumulate, and we know too well of numerous examples of self-destruction. The problems of sustaining a career without entrapment are manifold, and the lure of celebrity can be fool’s gold. The glare of the spotlight heightens human flaws, and, if Truman Capote is today a name that evokes a warning, we also have to remember that his ascent was as remarkable as his fall.

As his biographer has noted, Truman Capote had a high opinion of his own gift—and not without justification, as his best stories show:

No one valued his rich gifts more than he did himself: there was no other American of his generation, he felt, who had such a clear ear for the music and rhythm of the English language, no one else who wrote with such style and grace.

Indeed, one of his most prolific and aggressive competitors, Norman Mailer, even when advertising himself, endorsed Capote’s self-esteem:

Truman Capote I do not know well, but I like him. He is tart as a great aunt, but in his way he is a ballsy little guy, and he is the most perfect writer of my generation, he writes the best sentences word for word, rhythm upon rhythm. I would not have changed two words in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which will become a small classic.

Obsessed with “the inner music words make,” Capote knew that “Style is what you are,” but he lived long enough to contradict himself in all his self-destruction. Unable to resist various fascinations, he felt that he had used up the world and seemed in the last part of his life to welcome death.

That story has been told brilliantly and in perspective by Gerald Clarke in his Capote: A Biography (1988), surely one of the most readable and fascinating biographies ever penned about a penman. That biography supplies everything that is needed to piece out the story of Capote’s life insofar as it cannot be understood from the edition of letters that Clarke has now released. Born Truman Streckfus Persons in New Orleans in 1924 to an unstable woman who wanted to abort him and to a man who was a hustler, Capote would later take the name of his mother’s second husband. The boy would grow up fearing abandonment, and no wonder, for his parents abandoned him again and again. His many later attachments to glamorous women were derived from his distrust of his promiscuous mother, who wound up an alcoholic suicide, as, in effect, in 1984, did he. This fear became a free-floating anxiety that never left him—it is the “mean reds” (as opposed to blues) of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Truman Capote, like Henry James, had “the imagination of disaster”: At the age of 22, describing a love affair with a noted professor, he wrote,

Did you ever, in that wonderland wilderness of adolesense [sic] ever, quite unexpectedly, see something, a dusk sky, a wild bird, a landscape, so exquisite terror struck you at the bone? And you are afraid, terribly afraid, the smallest movement, a leaf, say, turning in the wind, will shatter all? That is, I think, the way love is, or should be: one lives in beautiful terror.

Such was the sensibility and the expression of the author of Other Voices, Other Rooms and A Tree of Night, but there is not much of that tone of Gothic lyricism in Capote’s letters.

Indeed, the first of Capote’s letters is a brusque notification to his father that he had repudiated his name. Thus, to the 12-year-old, writing was a means of establishing identity, and, when he could no longer write, the end was near. The overall burden of these letters, however, is far from lugubrious—quite the opposite, in fact, their tone being mostly joyous, zestful, and eminently social. Capote’s letters, being funny, are fun. For example, there are his terms of address and endearment: He calls a male adult “Peaches precious” or “lover lamb” or “Blessed Plum.” His favorite valediction is “mille tenderesse” [sic]—no more than a warm-up for his butchering of the French language at the most elementary level. “Quel travesty!” he remarks of a photograph of himself; of Los Angeles, “Quel hole! . . . Better Death in Venice than life in Hollywood.” Or again, “C’est marvelleuse” [sic] and “Merci buttercups cherie pour la letter . . . ” But aiming “oodles of passion” all around, Capote can be nasty as well as charming. Annoyed by an article by Diana Trilling, in which she had complained about homosexuality in postwar literature, he opined, “If Diana wants really to know about this ‘alarming’ increase in dickey-lickers [sic], all she has to do is sit down and take a square look in the mirror.” Years later, there would be other women who received the back of Capote’s hand, for much less reason.

Truman Capote seems to have written letters chiefly to amuse his friends, to spread the news and the gossip. And he insists that one of the reasons he writes letters is to receive a letter in return. Of course, Capote writes often because he is “away”—he was a restless man and thought that a new location was good for writing. He spent most of the 1950’s out of the country, a circumstance that alone provoked many letters. Here, I believe that all the travel reflections and the culture-vulture gossip eventually point up a lack, for Capote had hardly any historical sense at all. He seems to think, or rather to assume, that the traditional cultures of Italy, Sicily, and Greece are merely stage sets for him to enjoy. So he gives you a Sirmio without any of its poetic associations and a Taormina without any historical penumbra. Truman Capote was an autodidact who ignored school—his was a sensibility that relied on intuition and empathy and “emotional intelligence.” When he lost his edge, he had little to fall back on.

These letters record the personal life of a man who, by sheer force of personality, carved out a spectacular ascent into the world of literary logrolling, publicity, and jet-set high life. Capote was a celebrity in the late 1940’s, nationally recognized and always remembered for one particular image: the glossy, recumbent come-hither regard that graced, if it did not disgrace, the dust jacket of Other Voices, Other Rooms in 1948. Combined with the Southern Gothic obscurantism and homosexual narcissism of that novel’s discourse, Capote’s path seemed—but only seemed—to be set, and it was later confirmed by the stories in A Tree of Night (1949). The Grass Harp (1951), a Gothic-lite novel, showed Capote in another, essentially comic mode, while the film script for John Huston’s Beat the Devil (1953) is still, like the film itself, valued today.

Truman Capote’s diversions into reportage opened up new possibilities, and he needed them. The Muses Are Heard (1956), his account of the foray into Russia of an operatic troupe, was and is a toot. The sharp observations and humor show something of Capote’s particular gifts. When the high-spirited Capote elicited titters on the streets of Leningrad, he replied, “Laugh, you dreary people. But what will you do for laughs next week, when I am gone from here?” After another of his exhibitions, a Soviet bureaucrat intoned, “Ve have them like that in the Soviet Union, but ve hide them.” Yes, and in America, ve put them on TV.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958), a work of charm that is basically an exploded short story, featured the Holly Golightly subsequently trashed by Hollywood. The heroine, though she has numerous female models, was also based on the author himself, who, like Holly, had come from the provinces to New York, and who lived a free and whimsical life in the big city. After Tiffany’s, Capote went to a place no one predicted.

These letters also record much of the gossip of the international homosexual community, with its French and English extensions, that Capote explored and exploited. Capote knew Gide and Coc-teau as well as Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, and he had connections that joined, at least for him, the New York publishing crowd with the hip writers, and the worlds of Hollywood, Broadway, the arts, and high society. As the years went by, the culture, if it can be so designated, of the fabulously wealthy became more and more important to him, and he was already planning his pseudo-Proustian attack on the hostesses he had cultivated in 1958, before his obsessive detour into a remarkable project of literary slumming of a quality that Poe, Dickens, and Dostoyevsky had known.

The little newspaper item that brought the massacre of the Clutter family to Capote’s attention took him into the remote heart of the country. Strangely enough, the exuberantly sophisticated author had an affinity not only for the familiar and the homely but for their connection to the grotesque and the brutal. The letters tell us something about his exhaustive investigation and the years of “needlework” or painstaking composition that followed. In Cold Blood (1965) was Capote’s big hit and his bid for serious recognition, which he deservedly received in spades. But the exhausting engagement with the material and, particularly, with that pathetic wreck of a man, that pitiable murderer and other self, Perry Smith, cost Capote dearly, and he never recovered from the ordeal. When he witnessed the hangings, something in him died, too. Possibly the famous masked ball that Capote staged in the Plaza in 1966 was an attempt to recover from the damage, but that damage was irreparably done.

I find nothing more impressive in these letters than the advice that Truman Capote gave to Alvin Dewey III (the son of the agent of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation who is a major figure in In Cold Blood), who had asked for some help with his writing. Capote responds with sage advice, balanced, clear, tasteful, discreet, and kind. This is the Capote who was known to some as a man of high intelligence and keen sensitivity—a man who was a true friend and a writer of taste and discrimination. But we would have to say that this Capote is not always on display.

After the 60’s, the letters tail off and die as their writer did. Capote had become confused. He never understood why his rich intimates regarded his portrayals of them in Answered Prayers and elsewhere as betrayals, but make no mistake about it: They were betrayals. Now, maybe those ladies and some gentlemen had been foolish to allow a writer into their confidence, but nevertheless, a personal confession is not meant to be broadcast, the inherent ruthlessness of writers notwithstanding. And these tangles were not the only confusions that distorted and then destroyed Capote’s career and life.

Losing the discipline that had always sustained him, he began to surrender to temptations he had always known: the spiral of depression, alcohol, and exhibitionism, to which he now added drugs. Capote had to be led from the stage on occasion and accepted the role of buffoon on national television broadcasts, clowning for Johnny Carson and indulging in bitchy snarkiness (or was it acute observation?), saying memorably of Meryl Streep, for example, “She has eyes like a hen.” But Capote had by then become one of the dreary people himself, not gay but terminally morose, wooden on film, drunk on stage; and so there were, toward the end, no letters from the man of letters. Decline and fall is one of the most daunting stories in the history of American literature—so much so that, when Norman Mailer called the death of Capote “a good career move,” strictly speaking, he was right. The blurring of the distinctions between life and art were not so much a symptom as a cause of Capote’s destruction.

But to turn to The Complete Stories is to go back to the establishment of his career. First published in magazines such as Mademoiselle and Harper’s Bazaar, most of the early work today seems mannered and obscure. Visions of narcissistic entrapment, doubling, doom, and psychic disintegration are more frustrating than revelatory, but “Among the Paths to Eden” (1960) is an example of the precise diction, tonal mastery, poised charm, and satisfying surprise that constitute the Capote hallmark.

Perhaps “A Christmas Memory” (1956) is the great exception among the stories, because it is so obviously appealing. Tellingly enough, the memory is one of childhood, a subject which, for Capote, banishes all that is strained, for with it he is most comfortable. The recollection of humble Christmas rituals is a love story of a kind and, above all, a presentation of what is gone, and gone forever. The wound will never heal. Touching on regions of the cozy, the cute, and the smarmy but never encroaching on them (Christmas at Dingley Dell is on the horizon), this affecting and effective work strikes at the heart because it comes from there. It shows Capote at his most appealing in writing a tale that is universally accessible, in part because it is no story at all. It is, simply, a memory—rendered by the man who, 50 years later, would answer the phone during the holidays by saying, “Jingle, jingle.” No amount of Stolichnaya could erase the bitterness.

Speaking of bitterness, a later example is “Mojave” (1975), which is part of Capote’s unfinished Proustian project. The story has a cunning design of reflecting stories within the story, the burden of the juxtaposition being the impossibility of love. (The one who is loved never returns the emotion that is invested.) This story is admirably crafted and inflected, though its underlying misogyny is unjustified and may simply be a cover for homosexual frustration and resentment. To compare a woman to a snake because “The last thing that dies is their tail” is a bit less than profound and may merely indicate that Capote’s pose as the confidant of women was also a platform for homosexual revenge. The story shows that, even at so late a date, Capote could still compose with the best of them; but it also shows that his artistic judgment had become flawed by emotional pollution—the agenda was writing the story, rather than the story being the agenda.

The story here is not the stories he wrote or the letters he left but that of a man who attained a share of glory and then lost it all, or perhaps threw it away. Truman Capote was a funny man and a charming one, who was overwhelmed, finally, by his own dark side, “the mean reds.” If his letters are not great ones, nor his stories quite the cream of his work, they are nevertheless more than welcome, rewarding the attention paid them. For people who value the possibilities of writing, Capote the craftsman will always have a place on the shelf; for some others, no Gothic exploration that he inscribed will ever be as scary as the one that he lived.

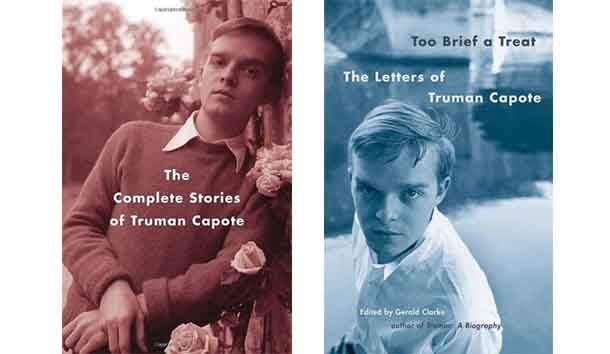

[The Complete Stories of Truman Capote, Introduction by Reynolds Price (New York: Random House) 300 pp., $24.95]

[Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote, Edited by Gerald Clarke (New York: Random House) 487 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply