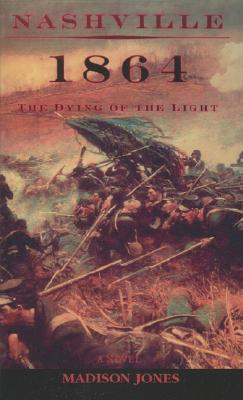

While Cold Mountain, the admittedly well-wrought novel about a Confederate deserter, has achieved bestseller status, a story of a quite different sort has gained a modest but devoted readership and demonstrated anew the gifts of one of America’s finest writers.

Nashville 1864 is a mere 129 pages long. Still, it is best not read in the rush of a single sitting, since Madison Jones, as William Walsh declared in a recent issue of the Chattahoochee Review, is “the greatest unknown novelist in the United States, if not the world.” Indeed, my own admiration for Jones’s work is so large, my indebtedness as reader to his gifts (and generosity) as author so deep, that my observations on Nashville 1864 must place his latest novel within the context of an achievement that is among the greatest in contemporary American letters.

Jones is probably known to the general reader only indirectly as the author of An Exile, a novella that became the basis for the movie I Walk the Line. I have never seen the movie, or, if I have, I’ve forgotten it; the novella is an unforgettable masterpiece that explores the mysterious foundations of the human personality, and the presumptions of superficial virtue. The complex interrelationships among temptations, the pride that goeth before a fall: these are the difficult themes to which Jones elegantly attends. Walsh is correct when he writes that Jones’s “novels are as universal as those of Faulkner, Hardy, and Flaubert, and as framed in the architecture and tradition of the Greek tragedians as one would hope to discover.”

Another name—another sensibility—with whom Madison Jones invites comparison is that of Flannery O’Connor. The hardfisted Larry Brown, a genuine heir of Faulkner, found himself thinking of Jones after reading O’Connor’s letters in The Habit of Being. Brown’s reflections are notable:

[Jones’s] novels . . . possess that relentless forward drive of narrative while allowing the reader to witness the ordinary things of life with great clarity, things like weather and the seasons and the way the sky looks in the morning after a good rain. The South that he writes of is a vivid, mysterious place in certain scenes, and in others it can be as familiar as the back of your own hand. [Jones] gets you deeply and personally involved with his people and their struggles. Like all the best writers, he allows you to lose yourself so fully in his work that the words on the paper begin to assume real life, the people breathing and moving and acting on their own. It’s as if these novels were simply found somewhere, already formed, and not written page by page, month after month, year after year.

Brown wrote those lines after reading Miss Flannery’s letters and Jones’s A Buried Land—one of the finest novels of our time—and A Cry of Absence, arguably the best novel ever written on the realities of race in the South.

All of which is the necessary prelude to appreciating Nashville 1864, Jones’s latest work is a novel written in the form of a memoir recently discovered by the grandson of the fictional author. The memoirist, Steven Moore, in 1900 recorded his adventures of 36 years earlier when, as a boy of 12 with his slave and friend Dink, also a boy, he set off, into the countryside of Tennessee, to search for his father, a Confederate soldier. From this story, Madison Jones has created one of the finest fictional recollections of boyhood ever written. Moreover, he makes the time, the countryside, the way of life, and—not least—the war present to the imagination and the senses. He captures what it meant (and may still mean) to be a Southerner, as well as, more particularly, a Tennessean. He writes straightforwardly, poignantly, and truly of what slavery in the South was not, and of what it was: Dink is beautifully and lovingly drawn. Further, Jones’s evocation of fatherhood is a great achievement in itself

In my memory Father, like the rest of us, including the horse, abides there frozen out of time, he by much the taller looking gravely down into my mother’s face. No movement, no sound. I suspect it may not have been just so in those moments, but always when that picture comes back into my mind it is fused with a kind of despairing sadness engendered by an ancient fold ballad my mother used to sing sometimes. It contained these lines:

All saddled and bridled and

gallant to see,Home came his good horse

But never came he.

I have never since heard that ballad, or read it in a book, that I did not shed a few secret tears.

After several paragraphs in which the father’s leave-taking for war is poignantly retold, these lines occur: “This was the end of that conversation. Unless you could call the minute or two that followed, in which my father did something he had never done before, a silent extension of it. He put his hand and held it there on top of mine on the fence rail. I thought of it as the laying on of my commission, the moment of my resolve to act, as far as I was able at ten years old, the part of a grown man. Even the thought was a heavy burden.”

Two years later, the boy of 12, after a perilous journey across the ground of the very decisive bloodbath around Nashville, sees his father again:

There, supported by helping hands on either side, was the man who was my father: my father with his head drooped down and snow-white bandage tied across his face. Not so, I thought and almost said on the impulse of a moment. Then it was gone, displaced by a burning blinding rush of tears into my eyes. So it was that I watched him come on, obscurely near and nearer, a figure swimming as it were in the hot flood of my tears.

Not insignificant to either the story or to Jones’s entire career as novelist is the subtitle, taken of course from Dylan Thomas. One must leave to the reader the discovery of its confessional quality. yet Miss Flannery deserves the last authoritative word, having remarked well over 30 years ago of Madison Jones, “He’s so much better than the ones all the shouting is about.”

[Nashville 1864: The Dying of Light, by Madison Jones (Nashville: J.S. Sanders & Company) 129 pp., $17.95]

Leave a Reply