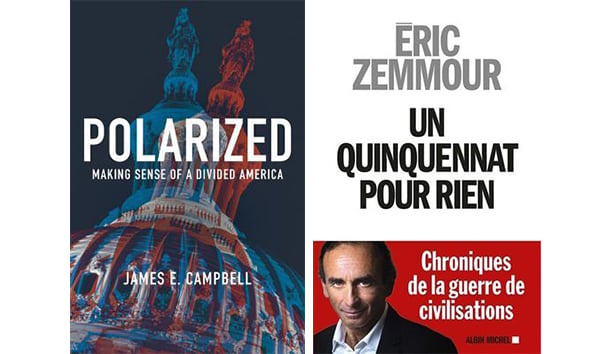

Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America, by James E. Campbell (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 313 pp., $29.95). This book is probably too academic to suit the taste of the general reader. It is, however, eminently sensible and notably well written for an academic text. Campbell argues that the polarization of American politics began in the late 1960’s as Americans began to grow less centrist minded, and that the polarization of the political parties followed from this fact, rather than being the cause of it. “There are more liberals [since then] and even more conservatives.” Party realignment was the result of the reconfiguration of the two main American parties in ways that reflected the increased polarization of the electorate (not gerrymandering, activism, the media, etc.). When the Democratic Party ceased to be divided against itself (Southern conservatives versus Northern liberals), polarization between it and the GOP became “symmetrical.” Further, “the crucial median voter of the electorate in any election is not a fixed point. The position of the electorate’s median voter moves with the size and turnout of each party’s non-centrist base.” Consequently, the benefit of a large noncentrist vote is necessary to the electoral victory of either party. Campbell is not among those who deplore polarization in itself. Rather, he argues,

When the will of the people is divided, as it is, similar divisions should be expected among responsible democratic leaders. Sometimes a non-decision is effectively a decision. In this sense, inaction in many areas of policy-making actually indicates that the government is fairly well aligned with the polarized public it was elected to represent.

So far so good. But Campbell, who urges greater tolerance among the public for views and opinions the opposite of their own, seems not to appreciate the ontological disagreements between modern liberals and conservatives that make tolerance impossible—in the matter of abortion and homosexual marriage, for two instances. The fact that the political polarization of the American public began in the revolutionary 60’s should have alerted him to the irreconcilability of liberal and conservative voters a half-century later.

Un quinquennat pour rien, by Éric Zemmour (Paris: Albin Michel; 539 pp., €22.90). Readers who read French, or are sufficiently interested to look up information about the author and his work on the internet, will be delighted to discover Éric Zemmour, one of the most uncompromising voices on the French right today. As a Jew whose native land is Algeria, he is in some ways more French than the French, for which his compatriots should be grateful. A “quinquennat” is the five-year term to which a French president is elected: Zemmour’s title in translation is “A Five-Year Term for Nothing.” Like its immediate predecessor Le Suicide français, reviewed in this space a year or so ago, the present book consists of a series of commentaries focused on significant events as they occurred day by day and year by year, in this case between January 8, 2013, and July 6, 2016, and prefaced by a lengthy Introduction that should be reprinted separately from the book itself. Zemmour accuses the socialist government of François Hollande of pursuing an economic policy that “takes with one hand what it had taken with the left. All the rest,” he adds, “is communication and manipulation.” Yet he is equally critical of Marine Le Pen, the leader of the Front National, whom he accuses of having abandoned her father’s concern for maintaining France’s identity, once described by Jean-Marie Le Pen as that of “a European people of the white race, Greek and Latin in culture and of the Christian religion.” France is past the point, Zemmour argues, of fretting about her sovereignty in relation to the European Union, which, though it remains a major concern, is no longer the central one. “Henceforth, France no longer fights to recover her lost sovereignty, but to retain her French identity. She no longer fights to live free, but in order not to die.” I have suspected for some time now that the country that gave us the French Revolution and the Rights of Man may be the Western nation that launches the counterrevolution in the 21st century. If so, Éric Zemmour may prove to be among her Voltaires, her Rousseaus, her Diderots.

—Chilton Williamson, Jr.

Leave a Reply