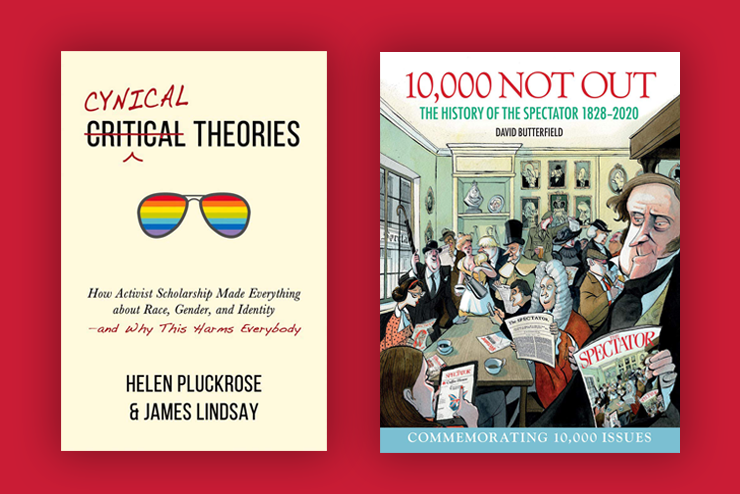

Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody, by Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay (Pitchstone Publishing; 352 pp., $27.95). To understand wokeness, I often ask students to explain why they add the word “social” to “justice.” They have yet to provide a satisfactory answer. My subsequent requests for clarification induce paroxysms of frustration. Luckily, this book has now rescued me from my generational ignorance. Its authors explain how social justice makes students “skeptical of science, reason, and evidence,” “read power dynamics into every interaction,” “politicize every facet of life,” and “apply ethical principles unevenly in accordance with identity.”

The authors pinpoint how this ideology grew out of the distrust of liberal social orders following the enormity of the two world wars. The left’s all-consuming alternative ideology, Marxism, also failed, as the unsurprising bankruptcy of collectivist countries proved. Man eventually realized the God of Scientific Progress didn’t care about him. Traditional conservatives won’t dispute the left’s assessment of the soulless postwar decades as “an artificial, hedonistic, capitalist, consumerist world of fantasy and play.”

Postmodernists eagerly injected their nefarious philosophy into that spiritual vacuum in accord with two principles: skepticism about whether objective truth is knowable, and the belief that knowledge is determined by the power structures of society. Neither sanity nor logic could escape postmodernism’s metaphysical black hole. You’ve probably rolled your eyes at the mishmash of academic theories it inspired which defile university curricula today—postcolonial, queer, critical race, intersectional, feminist, and gender, each of which gets a full chapter in this book.

But your eyes will absolutely pop out of your head when you learn their votaries demand scholars preferentially cite women and minorities while minimizing citations of white Western men to conform with “research justice.” If that sounds arbitrary or vindictive, then you’ve failed to grasp that knowledge “rooted in evidence and reasoned argument is an unfairly privileged cultural construct of white Westerners.”

“Woke” academicians promote other, subjective forms of research, like superstition, spiritual beliefs, identity-based experiences, and emotional responses as the preferred elixir.

Otherwise sensible alumni may blithely dismiss their alma maters’ acquiescence to such craziness. But Frankenstein’s monster has just graduated with his master’s in Fat Studies. According to his LinkedIn page, he’s now busy tearing down statues, peacefully protesting, and writing op-eds for The Washington Post.

(John Greenville)

10,000 Not Out: The History of The Spectator 1828-2020, by David Butterfield (Unicorn; 224 pp., $30.00). Few journals have cut such a dash through history and culture as The Spectator, and none have lasted as long. David Butterfield has immersed himself to excellent effect in the British magazine’s billion-word digitized archives, paying tribute to a unique institution as influential now as at any time in its 10,000 issue history, and one miraculously still commercially viable.

His main aim is to show continuities of feeling and thought across all the incarnations of the magazine over 192 years and under 29 editors. The Spectator is sometimes dismissed as Tory press, but even when the journal has been edited by Conservative politicians, it has allowed contrarian views that have angered or embarrassed Conservative administrations. The Spectator’s co-editors between 1861 and 1897 said their object was to protect “the right of free thought, free speech, and free action, within the limits of law, under every form of government.”

Robert Rintoul started the magazine as a means to numerous liberal ends, naming it after Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s eponymous earlier journal. It soon became a formidable champion of causes from abolitionism to electoral reform. Later editors were less obvious crusaders, but Rintoul would probably have approved of their generic dislike of “the Establishment” and the “nanny state,” which are common phrases that originated in Spectator articles.

Its best-known contemporary contributor is the irrepressible Taki Theodoracopulos (also of this parish), who has been delighting readers, appalling prudes, and causing awkwardness for editors since 1977 with his inimitable blend of high-society anecdotes, humorous insights, and outspokenness. It published right-wingers such as Enoch Powell, Roger Scruton, and Oswald Mosley, but also disparate personalities on the left, such as art critic Anthony Blunt, literature critic Terry Eagleton, and the double-agent spy Kim Philby.

But politics is only part of The Spectator, and maybe not even the most durable part. From the outset it gave generous space to the arts, carrying a glittering array of writers from Auden to Waugh, by way of Conrad, Eliot, Forster, Greene, Hardy, Lawrence, Nabokov, and Sartre—not to mention passionate arguments over apostrophes, etiquette, classical learning, clubmen’s gossip, nostalgia, bridge, and chess.

If sometimes narrow-minded and nepotistic, overall The Spectator has shown a rare openness to new ideas and talents. Butterfield’s book demonstrates that it has simultaneously helped make and mirror the British psyche, and to read it is not just to read the mind of the British right, but also the heart of a complex country.

(Derek Turner)

Leave a Reply