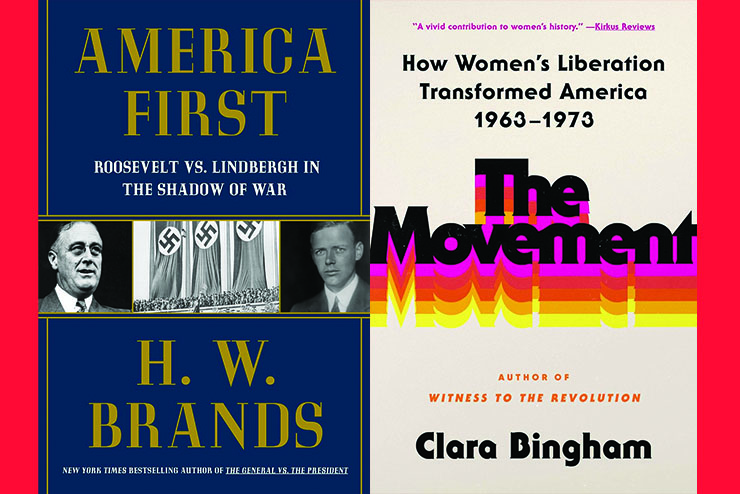

America First, by H. W. Brands (Doubleday; 464 pp., $35.00). In this history of America’s pre-war “America First” movement, H. W. Brands uses Charles Lindbergh’s private diaries and public statements to show us not a Nazi sympathizer, but a shrewd assessor of Germany’s military prowess; a proponent not of Nye Committee disarmament, but of boosting America’s defenses; and not a man who cowered when war came, but an eager volunteer.

Though Lindbergh’s attempt to participate in the war was at first squashed by the Roosevelt administration, which wanted to punish his earlier opposition, he circumvented that as a “civilian consultant,” flying 50 combat missions in the Pacific Theater.

While Lindbergh acted as a political innocent, Roosevelt the consummate politician advanced his cause through calculated falsehood. He preposterously claimed possession of a Nazi map outlining the Reich’s plans to transform Latin America into five puppet regimes, including what Roosevelt called “the Republic of Panama and our great lifeline—the Panama Canal.” The map and the plans were actually concocted by British intelligence, which the president almost certainly knew, yet he nevertheless lied to the American people.

Lindbergh harmed his anti-war cause through an impolitic at best, and immoral at worst, indictment of Jews as working against America’s interests. Ultimately, however, it was Germany’s declaration of war that shuttered the America First Committee. Brands concedes Lindbergh prophesied much correctly:

He argued that a war on the side of Russia would be no war for democracy. The war delivered half of Europe to communism. He feared that if Roosevelt succeeded in using the war to get elected a third time, he would become president for life.… Lindbergh contended that if Congress and the American people failed to resist Roosevelt, the legislative control over war-making decreed by the Constitution would be lost forever.

America First depicts the younger Lindbergh as the partisan of a bygone America and the older Roosevelt as posessing prophetic vision. “Sooner or later,” he concludes, “countries get the foreign policy they can afford.” U.S. power allowed it to delve into the Eastern Hemisphere’s affairs and emerge more powerful. Brands wonders whether Americans can afford such an ambitious foreign policy today, which explains this debate’s endurance.

(Daniel J. Flynn)

The Movement: How Women’s Liberation Transformed America 1969-1973, by Clara Bingham (Atria/One Signal Publishers; 576 pp., $32.50). There is no better way to understand just how radical the women’s movement of the ’60s and ’70s was than by reading the words of its proponents. In an age when the feminist left never tires of attacking the personalities and interpersonal affect of conservatives (“Toxic masculinity! Mansplaining!”), it is useful to see how feminists talked about their early leaders.

Here is a description of Betty Friedan in the words of one of her comrades: “She was a very difficult person. She was hostile … neurotic, and very hard to get along with. She made a lot of people miserable.”

Those traits would be disqualifying for any male leader. But the speaker goes on: “Angry people make revolution, and Betty Friedan made our revolution.” This admission that the women’s movement was based on rage is something its critics do well to remember.

Other foundational figures of “the movement” are revealed here as extremist ideologues. Robin Morgan, the co-founder of W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), says that “man-hating is an honorable and viable political act” because “the oppressed have a right to class-hatred against the class that is oppressing them.”

The Movement endeavors to make abortion activists of this period look heroic, but inadvertently reveals just how dishonest their rhetoric was. One woman tells the story of her desperate need for an abortion after a pregnancy with her boyfriend because “it was a new relationship … and I wasn’t about to have a baby with him.” He later became her husband, and she had two children with him. We are constantly told by “reproductive rights” activists that most if not all abortions are life and death matters, but convenience appears to be the more common reason for killing unborn children.

Other stories demonstrate how casually these “women’s health” activists regarded the well-being of real women. Several recount working, without medical training, at illegal abortion centers. “[W]e were empowering ourselves to do something out of the box,” one of them says. In this time period, hundreds of American women annually lost their lives as a result of this “out of the box” empowerment.

(Alexander Riley)

Leave a Reply