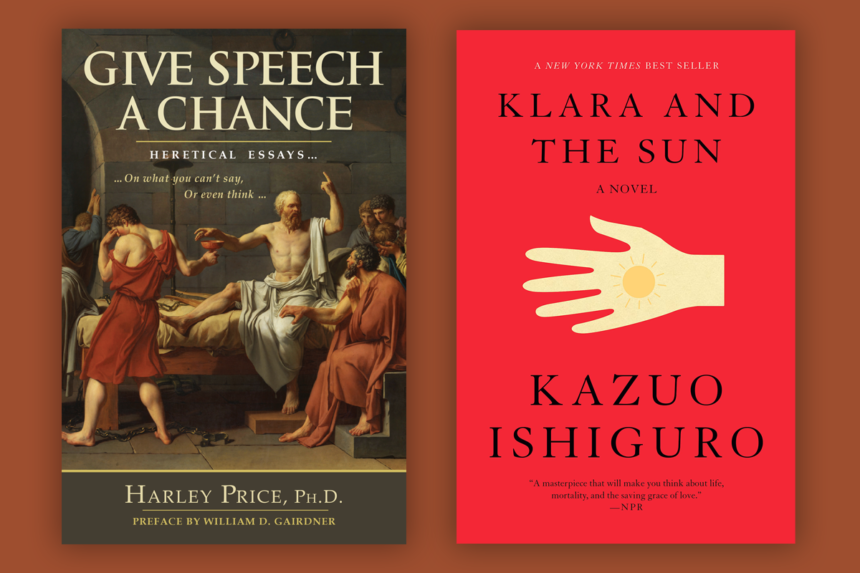

Klara and the Sun: A Novel, by Kazuo Ishiguro (Knopf; 320 pp., $28.00). A conservative disposition imposes costs but limits downside surprises. If you always expect rain, you have to lug your umbrella around wherever you go. But you never get wet. Likewise, if you see life through a Menckenian lens, worstcase scenarios sometimes play out, but rarely as bad as originally feared. Kirkus Reviews recently hailed Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Klara and the Sun as a “haunting fable of a lonely, moribund world that is entirely too plausible.” Jaded Chronicles readers will more likely come away from the Nobel laureate’s latest work thinking, “One man’s dystopia is another man’s utopia.”

Ishiguro’s tale takes place in a future where parents buy robotic Artificial Friends (AFs), which are human simulacra almost indistinguishable from real people, to amuse their solitary, anxious homeschooled children. A lonely, terminally ill teen named Josie shopping with her mother at an AF store one day decides to take the book’s narrator, Klara, home as a companion. Unknown to both Josie and the endearingly naïve robot Klara, Josie’s controlling mother has planned all along for an AF to replace her daughter once she dies. The devious mother has even hired an artist to make a perfect “body portrait” of Josie, which Klara will then animate.

But when Klara’s prayers to a deified sun (she’s a solar-powered robot, after all) to heal Josie are miraculously answered, our heroine Klara ends up in the AF junkyard. No good deed goes unpunished in robotkind’s earnest future.

Editors should demand that Ishiguro use his imagination the next time he conjures up a fictional dystopia. Klara’s apocalypse arrived 20 years ago by my count. How many Artificial Friends do American teens already have on Facebook, Instagram, and Match.com? Tinder and Grindr essentially match AFs for sex purposes. Reading about Josie’s online tutoring sessions gave me paralyzing flashbacks of teaching over video conferencing software last year. And her overbearing mother’s abominable behavior reminded me of a college counselor friend who told me of one client’s homicidal rage when Stanford rejected her son. Pity, he will have to suffer at Princeton instead.

Ask a Chronicles reader to describe dystopia. He might mention the ballooning U.S. national debt sparking a Weimaresque inflation, a Camp-of-the-Saints style invasion overwhelming our southern border, or identity politics ending in a catastrophic racial war. But Ishiguro’s electronic devices mesmerizing depressive teens with impersonal electronic friend requests? That’s just a description of what we’ve got right now.

(John Greenville)

Give Speech a Chance: Heretical Essays, by Harley Price (Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation; 395 pp., $25.00). This is a dazzling collection of mordant essays on our aberrant Zeitgeist by a medievalist from the University of Toronto. No disrespect is intended to the estimable figure to whom this volume is dedicated, the late Joe Sobran, to suggest that Price may be refuting the praise that he bestows on his hero when he assures us that “none will approach his brilliance, eloquence, or wit.” At least this reader discerns in Price’s argumentative verve, elegant self-expression, and defenses of Catholic moral teachings ample evidence that he shares Joe’s special talents.

It is hard to imagine a more worthy successor to Sobran than Price. Whether he engages victimology, atheism, abortion, sex education, universities, conservatives trying to “turn back the clock,” or any one of his many other themes, he presents his “heretical” right-wing views trenchantly and in language that I can only envy.

It is highly doubtful that Conservatism Inc. will review Price’s book. It is too devastating in how it goes after the cultural left without ascribing good intentions to the enemy. It is not the stuff that could possibly lead to “dialogues” with the people who “count.” Those who throw lightning bolts like Harley should also not expect advance contracts from commercial houses for respectfully responding to the left. He does not play by the rules of the official opposition.

Although it is hard to pick a favorite polemic from this treasure trove, as a political theorist I particularly relished Price’s remarks about “the human rights Stasi.” Although Sobran once said something similar about the “human rights” industry, Price expresses the same criticism perhaps even more caustically:

It tells you something that you’ll never hear white males, property owners, businessmen, the ‘rich,’ or conservative Christians celebrating that some new civil rights legislation has just been passed. They know intuitively that, with the promulgation of each new entitlement or equity measure, their own rights and liberties are about to be further curtailed.

If we exclude multinationals and corporate executives as victims of the human rights scam, the rest of Price’s observation seems just about perfect.

(Paul Gottfried)

Leave a Reply