In his Introduction, journalist Peter Seewald, who talked to the Holy Father over several hours at Castel Gandolfo for this book, points out that it is the first time a pope has engaged in such a personal interview. Although Seewald’s questions appear at times a little convoluted and repetitive, he can rightly take credit for the scoop, for in this long “conversation” Benedict XVI reveals himself in a way not possible for the public smiling figure we have seen during papal visits or on our television screens.

What is revealed is a man at once engagingly straightforward and wholly bound up with bearing witness to the “truth, the love and the joy that comes from conversion to Christ,” as George Weigel writes in his Foreword. Prayer, the Holy Father admits, is “begging, for the most part.” It is also trusting and humble: His immediate thought on his election to the papacy was “I can’t do it. If you wanted me, then you must also help me.” Asked by his interviewer about comparisons between his pontificate and that of John Paul II, his great predecessor, Benedict simply replies, “I am who I am.” Not surprisingly, given both the burden of his office and his radical trust in God, his private motto as Pope is “Do not be anxious about tomorrow.”

There is also humor. Asked by Seewald if, like Churchill, he would say, “No sports!” the Holy Father instantly responds, “Yes!” Not a keen goalkeeper in his youth then, unlike John Paul II. Press speculation on his unusual headwear, the camauro, can now fall silent; it appears “I was just cold and I happen to have a sensitive head.” A further glimpse of his personality comes through in the fact that the Holy Father brought his desk and his bookcases, as well as his books, with him to the Vatican: “I know every nook and cranny and everything has its history.” The scholarly furniture of his mind is reflected in the actual furniture of his study. He also wears the watch his late sister Maria, who acted as his housekeeper, bequeathed to him.

Naturally, some of the conversation centered on the priesthood, a vocation that has been central to the Pope’s life for almost 60 years—ever since his ordination in 1951. Celibacy is possible to live “when priests begin to form communities . . . not to live on their own somewhere, in isolation.” But Benedict is clear that celibacy “cannot be a ‘pretext’ for bringing people into the priesthood who don’t want to get married anyway”—a reference to those of a homosexual orientation. Asked about the purpose of the recently concluded Year for Priests, Benedict sees it as a year of purification, of interior renewal and “above all penance.”

This last, a frank allusion to the scandal of child abuse, has brought him great suffering; the priesthood “suddenly seemed to be a place of shame.” Asked if he had considered resignation over the gravity of this scandal, the Pope characteristically replies, “When the danger is great one must not run away.” Several times during the interview he touches on the “mystery of evil”—referring to this abuse, to unworthy past holders of the papal office, and to the particular case of Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado, the disgraced founder of the Legionaries of Christ. Yet even here the Holy Father is not prepared to remain in a negative stance, reflecting on “the paradox, that a false prophet could still have a positive effect.”

It will not come as a surprise to readers to learn that Benedict, although speaking with his customary care and courtesy, believes the Church has greater “spiritual kinship” and “interior affinity” with the Orthodox Church than with Protestantism, whose closeness to “the spirit of the modern age” has made dialogue more difficult. Challenged over his Regensburg Lecture, which caused such a furor in the Islamic world, the Holy Father does not prevaricate. Islam, he states, still needs to clarify its relationship to violence and it relationship to reason. Yet as with other grave problems encountered in his papacy, he emphasizes that hope follows this serious crisis: 138 Islamic scholars wrote to him after Regensburg, asking for dialogue.

On the subject of Bishop Williamson of the SSPX and holocaust notoriety, Seewald is given a disarming admission: “None of us went on the internet”—the result being, in the Holy Father’s words, a “total meltdown.” Indeed, “our public relations work was a failure.” The same could perhaps be said of the advance media publicity given to one paragraph on page 119 of the book, the Holy Father’s response to a question about condom use. So much has been written and aired on this matter—and will continue to be in the months to come—that it hardly needs to be stated here that the Catholic doctrine on sex, love, and sexual relationships has not changed. In this conversation Benedict speaks as a pastor of souls, aware both of the gravity of sin and the mysterious possibilities of grace in the heart of a sinner. To me it brings to mind the quotation from Isaiah in St. Matthew’s Gospel: “He will not break a bruised reed.”

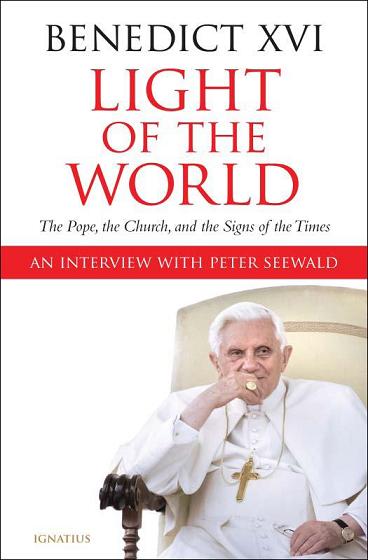

Was such an interview imprudent, as some critics have suggested? I do not think so. Everything the Holy Father says in his candid, considered responses revolves around his passionate belief in the one thing needful: coming to know God’s love and how this love is manifested in Christ through the Church. This is what the elderly interviewee in the white cassock, aware that his “forces are diminishing” and, since his election, no longer able to go for walks with his brother near his house in Pentling, Bavaria, wants to communicate. The book is well worth reading, not in order to find loopholes in the law or to rake up controversy, but to walk for a while in the company of a humble and holy man.

[Light of the World: The Pope, the Church and the Signs of the Times, by Pope Benedict XVI, with Peter Seewald (San Francisco: Ignatius Press) 239 pp., $21.95]

Leave a Reply