To 18th-century Britons and Americans who devoted any serious thought to the subject of human nature—and a great many did—the conventional starting point was the theory of the passions, or drives for self-gratification. Rousseau to the contrary, man was not naturally good but was ruled by his passions, both primary (fear, hunger, lust) and secondary (cravings for money, power, certainty, status). Reason could curb the passions only rarely and temporarily, and normally served merely as an agent of their fulfillment. Religion was still considered to be a necessary restraint upon them, but it was no longer thought to be a sufficient one. Given such a premise, the inevitable question arose, can man learn to comport himself morally, and therefore be free, or is he so thoroughly depraved that he is doomed to be oppressed by priests and tyrants?

Among those who contrived to reach an optimistic answer, perhaps the most common means was to posit a second premise, namely that the social instinct is one of the primary passions: The desire to secure the approval or at least to avoid the animosity of one’s fellows ranks as strong as the need to satisfy physical appetites. This belief underlay the 18th-century’s intense preoccupation with what the adolescent George Washington described as “rules of civility.” Every kind of social interaction—from ballroom dancing to warfare, from forms of address to the complementary closings of letters—became mannered, structured, stylized. Every person learned the norms that attended his station, and anyone who violated them forfeited the esteem of his peers and betters.

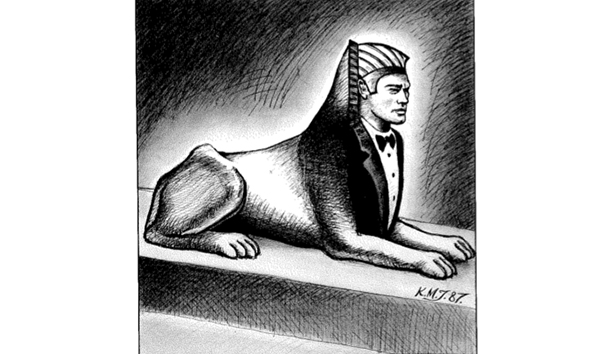

All this is fairly well-known to students of the period; what is less well-known is the related concept of character. In its most general signification, character meant reputation: So and so had a character for fickleness or probity or rashness. But it also, at least among persons in public life and polite society, meant a persona that one deliberately selected, cultivated, and attempted to live up to: A man picked a role, like a part in a play, and was expected to act it unfailingly: one must always be in character. If a fitting persona were chosen and worn long enough and consistently enough, it ultimately became a second nature that in practice superseded the first. In the end, one became what one pretended to be.

The results, for good or ill, depended upon the character and upon how well one played it. Miss Fanny Burney, in her extremely successful novel Cecilia (1782), depicts a rich variety of characters in fashionable London society, most of them rather shallow. There is a voluble, who sees everything in hyperbole and always talks faster than she thinks; there is a jargonist, who aspires to nothing but compliments in the “Lilliputian vocabulary” picked up in public places; there is a supercilious, who spends half her life desiring the annihilation of the other half. But the reigning arbiter of fashionable favor is the insensibilist, who affects boredom with everything, and thereby proclaims himself superior to all possibility of enjoyment. When Cecilia hears her mentor’s description of these empty people, she remarks that they would sicken of their folly and change their ways if they could only hear themselves exposed. No, he replies, “they would but triumph that it had obtained them so much notice.”

On the other hand, playacting could have an ennobling effect. Consider George Washington, who first sought the character of a gentleman, and then of a hero, and then progressively grander roles—self-consciously playing a part at every stage—until he had become Father of His Country and a veritable demigod. More common was the course followed by Thomas Jefferson, who struggled with a number of characters, even undergoing several changes of handwriting, until he found one he could play comfortably.

This brings us to Benjamin Franklin, the subject under review. Two new studies, both inspired at least in part by Yale’s monumental edition-in-progress of Franklin’s papers, have recently appeared. One is the work of a seasoned English student of 18th-century America, Esmond Wright, who has undertaken the first comprehensive biography of Franklin since Carl Van Doren’s appeared in 1938. The other is the work of a gifted amateur, Williard Randall, who has focused upon Franklin’s strange relationship with his bastard son, William. Wright’s study is judicious and informed, although he has overlooked some of the best Franklin scholarship of the past several decades. Randall’s is slanted and riddled with errors—yet it is a gripping tale in which William Franklin, as the last royal governor of New Jersey, emerges as a sympathetic and tragic-heroic figure.

Wright virtually ignores William, which is easy enough to do; except for a brief but impressive fling at soldiering, William’s only permitted character until he was in his early 30’s was that of the dutiful son. In that capacity, as Randall demonstrates, he was extremely helpful to a father who rarely gave him due recognition for what he did. (It was the son, for instance, not the father, who discovered that lightning moves from the earth to the heavens instead of the other way around, but Benjamin took credit for the discovery.) Then in 1762 William obtained, through his own connections, the appointment as governor of New Jersey. His character was now that of faithful servant to the King, and he played the role with great courage when the movement for independence came—suffering privation and imprisonment as a consequence, as well as never being forgiven by his father.

Both authors attempt to cope with the central and unavoidable problem in studying Benjamin Franklin: On the basis of the record as well as the judgments of contemporaries, Franklin appears to have been not one character but a multiplicity of them. His first important role is that of Poor Richard, the apostle of such bourgeois virtues as thrift, frugality, industry, honesty, independence, and the pursuit of wealth. Then comes the rationalist, inventor, and man of science, who demonstrates that lightning is electricity, invents the stove that bears his name, and advances sophisticated observations and theories about the movement of storms and the course and effects of the Gulf Stream. Next he has considerable success as a politician, gaining power as a demagogic champion of the people against the privileged few, while simultaneously becoming wealthy as a sycophantic placeman. (William indicated how far his character had departed from his father’s when he remarked a few years later that “it is a most infallible symptom of the dangerous state of liberty when the chief men of a free country show a greater regard to popularity than to their own judgment.”)

Meanwhile, Franklin is demonstrating his assorted skills as a city planner, military commander, and Indian negotiator, and became almost obsessed with gaining immense riches through grandiose land speculations. Years of service in London as agent for several colonies follow, years in which he lives voluptuously, joining hell-fire clubs and otherwise violating every Poor Richard adage. Then comes his ministry to France during the American Revolution, when he poses as the Natural Man, affecting a homespun republican simplicity and serving the American cause by obtaining indispensible aid from the French court. (Neither Wright nor Randall, by the way, deals with Cecil Currey’s plausible argument that Franklin played a double agent in Paris, serving both Britain and the United States.) Penultimately, there is Franklin the wily diplomat, negotiating the Peace Treaty that recognizes American independence; and finally, there is the venerable sage at the age of 81, infusing the Constitutional Convention with wisdom, piety, and moderation.

Will the real Benjamin Franklin please stand up? Randall attempts to reconcile the several characters by ripping off the various masks and revealing Franklin’s “true” character, in the 20th-century sense of the term. What emerges is a man of wit, charm, and talent who exploited and abused his son, deceived almost everyone, served his country, and was at bottom an opportunist and a scoundrel—what in Washington today would be called a survivor. Wright is more cautious. He quotes William Cobbett’s description of Franklin as “a crafty and lecherous old hypocrite,” and much of his narrative supports that depiction. But he also quotes Lord Kames’s view that Franklin was “a great figure in the learned world . . . who would make a greater figure for benevolence and candor, were virtue as much regarded in this declining age as knowledge.”

Wright sees beyond such judgments, however, and recognizes that Franklin was a self-made man in the literal sense, a manufacturer of myriad personae, a “manipulator of the strings to his own puppet marionettes.” It is pointless to ask whether there was a “real” Franklin beneath all the personae, Wright suggests, for “Franklin became the parts he played, even if some of them were inconsistent and contradictory.”

The conclusions of neither author are satisfactory. Randall wrenches Franklin from his 18th-century context, while Wright seems contented with Van Doren’s conclusion that Franklin was “a harmonious human multitude.” But what provided the harmony, the organizing principle, the larger character that unified the many small roles? I think it was this: Franklin set out at all times to play the part of the totally civilized and totally rational man, at once engaged and detached. By definition, it was impossible to play such a part; but, conceivably with the exception of Voltaire, Franklin came closer to pulling it off than any other man of the age.

[Franklin of Philadelphia, by Esmond Wright (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press) $25.00]

[A Little Revenge: Benjamin Franklin and His Son, by Willard Sterne Randall (Boston: Little, Brown) $22.50]

Leave a Reply