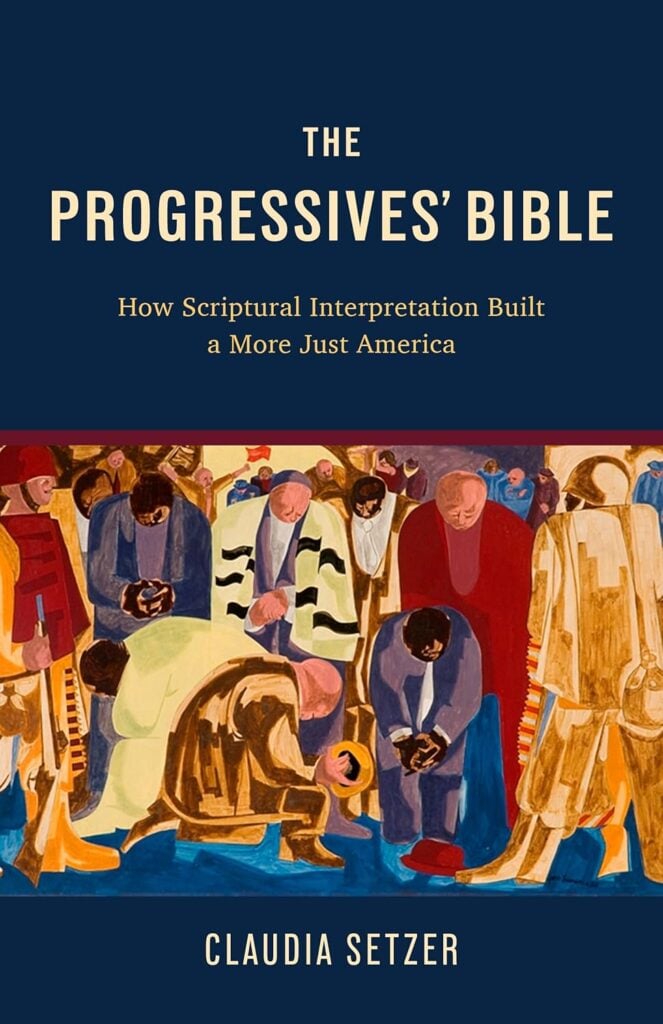

The Progressives’ Bible: How Scriptural Interpretation Built A More Just America

by Claudia Setzer

Fortress Press

206 pp., $29.00

Using the Bible to back up

political ideologies has a long history in America. More than a few examples of the practice take on the color of parody.

Recently, I stumbled upon an intriguing contemporary illustration. It concerned the unique exegetical skills of one John Fugelsang. In a panel discussion on The Michael Steele Podcast about the recent election, Fugelsang assured listeners that the God of the Bible is “the least pro-life character in the book” because of the infant deaths during Passover. Oh, and also because God “drowned every fetus in the world once because He was in a mood.”

Such are the wonders of biblical interpretive anarchy in the interest of ideology. The Progressives’ Bible offers examples of other abuses of the Bible over the centuries as a rhetorical foundation for the political causes and movements of the progressive left.

The book’s most compelling chapter is its first, on the abolition of slavery. Generations of abolitionists were predictably able to find support for their position in a religious tradition centered on the spiritual oneness of all humankind. Setzer gives some examples of abolitionist writers who used the Old Testament religious genre of the jeremiad to assail the evils of slavery. But even in her strongest chapter, Setzer’s biases are insufficiently bracketed. She approvingly gives a citation of the 19th-century African-American abolitionist Maria Stewart that she claims shows Stewart “predict[ing] a violent fate for white America and a blessed existence for her people.” This is right in tune with today’s antiracist groupthink, in which all whites are beneficiaries of slavery and all blacks are the very elect of heaven. But study the Stewart quotation closely and you find something rather more nuanced:

O ye great and mighty men of America, ye rich and powerful ones, many of you will call for the rocks and mountains to fall upon you, and to hide you from the wrath of the Lamb… whilst many of the sable-skinned Africans you now despise will shine in the kingdom of heaven.

It is not “white America,” top to bottom, but the “mighty” and “powerful” who Stewart said will be punished for slavery. And there is no indication in her words that all blacks attain paradise by sole virtue of their skin color. As a Christian, she knew well that all who reach heaven do so only after their particular judgment, not as parts of a racial collective seen by God as either spotless or eternally stained.

Setzer avidly criticizes Stewart’s “problematic” embrace of Ethiopianism, a movement that posited that slavery was a necessary means for the conversion of the slaves from heathenism. This ideology, she writes, was “internally conflicted.” But is it not true that it was by means of the slave trade that blacks came to the parts of the world in which they were Christianized? Why can one not even suggest that this was a profoundly positive aspect of an experience that also had profoundly negative consequences? The world is like this sometimes. Terrible events can have unexpected, complex effects.

Setzer also explores historical efforts to use the Bible to argue for equality of the sexes. These were significantly hampered by the fact that the Bible is not a radical feminist tract. It takes sex difference as a given. Many early advocates for feminist causes noticed this and accordingly avoided invoking the Bible. Some engaged with it only to attack it. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote a Woman’s Bible that trashed the biblical religious and moral tradition in the interests of radical political egalitarianism. Setzer is predictably underwhelmed by more measured women’s advocates, such as Phoebe Palmer of the Methodist Holiness Movement. Palmer called for “spiritual equality” while still recognizing different gender roles and a sexed division of labor.

The Bible’s firm traditionalism on the reality of sex difference has been no impediment to substantial social gains for Christian women. It is undeniable that women benefited comparatively from the birth of Christianity in their increased roles in church rituals and hierarchy, in greater rights and security in marriage compared to pagans, and through the faith’s negative view of female infanticide, which pagans practiced routinely.

The book’s last chapter deals with interpretations of the Bible by mid-20th century black civil rights activists. Setzer groups these figures into three traditions. The first is exemplified by individuals such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer. Here, the U.S. is seen as a country founded on Christian principles that needs to be put back in touch with its own origins to achieve racial harmony. A second view, seen in Malcolm X, is that the U.S. is committed to crushing blacks and Christianity is a tool for that project. The third tradition, which Setzer connects to Albert Cleage Jr., the founder of the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church, shares the black separatism of the second but transforms the traditional biblical narrative into a moral story about the liberation of blacks and the coming of a black messiah.

Few black Americans today have ever heard of Cleage. But there is no question that Malcolm X’s view of Christianity—that is, hostile antipathy—is now much more widespread, both among blacks and whites, than it was in his lifetime. The King/Hamer view is also still with us, even if there are many who would like to distance it from its roots in Christianity.

Setzer sees King and Hamer as religious radicals. She cites Hamer in 1963 apparently wrathfully imagining Southern policemen facing judgment. “It’s going to be miserable for you when you have to face God,” Hamer said. But she concluded that speech by enjoining activists to “smile at Satan’s rage” rather than mimic it, as is done in the contemporary antiracist protests that Setzer admires.

King is also, in Setzer’s reading, more wrathful than submissively Christian. She describes his 1969 essay “Showdown for Nonviolence” as full of “dire predictions.” But here is the core message of the text:

Nonviolence… may be the instrument of our national salvation… We need to bring about a new kind of togetherness between blacks and whites… We have, through … nonviolent action, an opportunity to … create a new spirit of class and racial harmony… I plan to stand by nonviolence because I have found it to be a philosophy of life that regulates not only my dealings in the struggle for racial justice but also my dealings with people, with my own self.

The book concludes with “Contemporary Progressive Movements,” a very thin chapter because the progressive left has moved so far from the Christian moral core of Western civilization. Setzer tries to connect the “MeToo” movement to Christianity, but the basic language of MeToo is the radical feminist victim narrative that “all women are at all times under menacing threat of rape in the patriarchy.”

Setzer also invokes Dayenu, a Jewish religious activist movement devoted to climate change, which takes its name from a song of gratitude to God sung during Passover. Yet on its webpage, Dayenu gives almost no religious foundations for its activism beyond a few brief and vague allusions to concepts of responsibility between generations, the value of life, and protection of the vulnerable. The movement explicitly says that one does not have to adhere to Judaism to join, and no use of the Old Testament to frame its social activism is found on its site. A strange example of “the progressives’ Bible.”

Setzer makes clear in this concluding chapter how she views the Bible. It is, she intones,

not innocent, and readers should not close their eyes to its inherent patriarchy and encouragement of violence toward other peoples, nor the ways it has been wielded to amplify patriarchy, racism, and colonialism in later eras.

That firm statement on the inevitably oppressive side of the Bible is contradicted in the book’s introduction, where Setzer assures us that no one “can say what it really means.” The more radically democratic varieties of Protestant Christianity bear the most responsibility for the interpretive anarchy underlying Sezter’s view of the Bible. In forms of Christian worship with deeper traditions and firmer hierarchies, no one agrees with the idea that the Bible has no certain meaning. Whatever we believe about the possible varieties of interpretation of the text, we can say some things with assurance about what the Bible does not even conceivably support. It does not tell us, for instance, that men can be women and vice versa; it does not tell us killing unborn children in the womb is a God-given right; and it does not tell us that victimhood, as opposed to its transcendence, is the goal of the faith.

Still, the book’s subtitle is not entirely incorrect. Some scriptural interpretation did help build a more just America. Christianity crucially informed abolitionism and the most effective and morally serious elements of the 20th-century civil rights movement. But understanding why it did so requires something more serious than the airy relativism of “no one knows what the Bible really means.” In looking to Christian thought for political guidance, the key is to recall that it is a religion, not a political philosophy, and its central moral values are forgiveness, the equal status of all human beings as transgressors against God in fact, and the call to reconciliation with one another and with God. There are no eternal victim and eternal victimizer collectives here, as there are in abundance in the leftist politics that inform books like The Progressives’ Bible.

Leave a Reply