“To write a criticism of one’s self would be an

embarrassing, even an impossible task.”

—Heinrich Heine

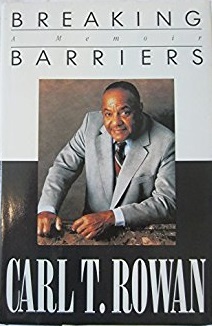

This autobiography pretty much confirms the impression left by an occasional reading of Carl Rowan’s columns over the years: a decent enough fellow, earnest but smug, amiable at times but given to portentous and endless scoldings about “hidden racism,” the lean civil rights champion turned puffed-up panel discussion bore.

To begin with the better part of Breaking Barriers: A Memoir, Mr. Rowan’s story runs like this. The future award-winning reporter, ambassador, and pundit was born in McMinnville, Tennessee, to a loyal and brave mother and a layabout father who seems to have squandered the few chances life gave him. Jobs were few, but even when he did earn some money stacking lumber or cleaning stables, the old man gambled much of it away.

“‘Boy, we’re gonna have a good dinner tonight, ’cause I just won eighteen dollars,'” he’d say after his more successful ventures at the poker table. But, recalls Mr. Rowan, “My mother always believed that if he said he had won eighteen dollars, he really had won twenty-eight dollars or more. So she would go through his pockets at night. And the happiness of ‘a good dinner’ would deteriorate into another brawl.” It continued like this throughout Mr. Rowan’s boyhood: a shanty home, endless quarreling, scrounging for food, rats, bedbugs, one slight or humiliation after another.

And there was “no road of escape,” he writes. “Every time I read the arrogant opinion of some white male about the weaknesses and sins of black men, I think back to the 1930’s and to a father who was a damned smart guy, except that he had been denied formal education and had no way to become a ‘good provider.'”

If there is more anger in that pronouncement than hard reason, we can certainly forgive this in a man who, growing up poor in a segregated town, awakened in childhood either to bitter parental shouting or the squealing of large rats. But sins and weaknesses are sins and weaknesses, no matter what the advantage of “some white male” who points them out—and who must struggle with sins and weaknesses of his own. In any case, young Mr. Rowan himself got a few rare breaks, chiefly in the form of a wise teacher, Mrs. Bessie Taylor Gwynn, who put sense into him. “‘I ain’t much interested in Beowulf,'” he recalls telling her. “‘Boy, I am your English teacher, and I’ve taught you better than this. How dare you talk to me with ‘I ain’t’ this and ‘I ain’t’ that. . . . You know what really takes guts? Refusing to lower your standards to those of the dumb crowd.'”

He did refuse, and so advanced to a segregated college, where he excelled. With the arrival of war in 1941, the Navy set out to recruit its first black officers, and Mr. Rowan was the very first selected. These successes, he writes, left him with “an air of haughtiness that would antagonize [whites],” though it’s not clear whether he came to regard this trait as a hard-won virtue or, like haughtiness in “some white male,” a defect to be reformed.

There followed the usual stupid insults, slights, and cruelties by whites, unaccustomed, circa 1941, to being around blacks,’ much less saluting a black officer. But there were also some nicer moments, as when Mr. Rowan’s superior introduced himself and dispensed orders to the new officer with no comment whatever about race or a “guess-who’s-coming-aboard” talk to prepare the men. Mr. Rowan appreciated that, “for without any do-gooder lectures, the skipper had shown an acute understanding of what I—and other Negroes—wanted: no special restrictions and no special favors; just the right to rise and fall on merit.” Thereafter the book traces the author’s own rise, on merit, to “award-winning reporter,” State Department spokesman, ambassador to Finland under President Kennedy, USIA Director under Johnson, and columnist right up to the present.

About those awards, though: here we encounter the flaw that dooms this entire book, the one “barrier” Mr. Rowan has not quite broken. Every award, every citation or certificate of merit, every medal, every commendation or honorable mention, and just about every bit of public praise the man has ever received, found its way into this book. “The Sidney Hillman Foundation gave me an award for ‘the best newspaper reporting in the nation in 1951,'” we learn. “The curators of Lincoln University . . . cited me for ‘high purpose, high achievement, and exemplary practice in the field of journalism.’ And then the almost totally white Minneapolis Junior Chamber of Commerce named me Minneapolis’s Outstanding Young Man of 1951!”

Soon afterward, “my peers in the journalism fraternity, Sigma Delta Chi, voted to give me the prized medallion for the best general reporting in the nation in 1953”; this for a series in the Minneapolis Tribune, “Jim Crow’s Last Stand.” “But before I could accept plaudits [from Sigma Delta Chi] I had another honor to accept. On January 2, 1954, the United States Junior Chamber of Commerce announced that I was one of America’s Ten Outstanding Young Men of 1953!”

Goodness gracious, and as if all those prestigious honors weren’t enough Mr. Rowan then garnered—May 18, 1955—”the coveted Sigma Delta Chi prize for foreign correspondence,” and on that historic occasion heard this said of himself:

Carl T. Rowan’s series [“This is India”] combines masterful investigative reporting with pungent writing and objectivity in the best journalistic tradition. Here are fact finding, initiative, clarity, and organization in proportions no newspaper reader, however indifferent, can ignore and no journalist, however high his standards, can fail to recognize as a model of inspired craftsmanship.

“A year later, on May 15, 1956, I was at the Sheraton Hotel in Chicago being cited for ‘best foreign correspondence of 1955’ for my articles on Southeast Asia and my coverage of the Bandung Conference. I had now won a coveted Sigma Delta Chi medallion three years in succession, something no journalist had ever done.” His children, Mr. Rowan notes, were right there in the audience to witness dad’s triumph—the first and nearly only reference to his kids at all.

Not for us to belittle these plaques and medallions, recalling that the recipient was only 15 years earlier fending off the rats. Whether or not any of the hardware with which so many journalists and politicians like to adorn their offices, reminders of their selfless “public service,” are really to be “coveted,” surely this particular reporter was entitled to covet them. No doubt each honor seemed to carry him further from McMinnville. The only problem is that his recollections of these ceremonies and presentations are not followed, ever, by any serious reflection on the events he was so “masterfully” covering.

That Bandung Conference, for instance. Here he was, a young black reporter, assigned to the Afro-Asian Conference held in April 1955 in Bandung—among liberals, regarded nostalgically as a milestone in Third World self-assertion. But we get not a word, 36 years later, on the fate of all those black “liberators” and leaders assembled at the historic conference; no wistful reflections on the dictatorships, invasions, civil wars, and massacres so many of them would inflict on their countries. That more than a few of the African statesmen young Mr. Rowan observed and interviewed would go on to perpetrate atrocities against fellow blacks, horrors beyond the imagination of their colonial predecessors or even the cruelty of Jim Crow, seems not to have registered on the memoirist. We learn only that he was thrilled to witness such “international high drama,” wrote a masterful series on the conference, and cleaned up at a subsequent awards banquet. Oh, yes, and we’re told his book about Bandung “was selected by the American Library Association as one of the best of the year, an honor it also bestowed on my South of Freedom.”

This leaves the unfortunate, and no doubt unjust, impression that the Outstanding Young Man of America was then, and remains, more interested in personal recognition than causes, even those about which he’s so passionate. And, too, it leaves a gnawing doubt about other of his recollections, particularly those extensive conversations he quotes verbatim—exchanges in which Mr. Rowan invariably gets the best of some powerful white male.

For instance, after some principled difference of opinion with then-Vice President Johnson, LBJ is supposed to have owned up, to his error, conceding gruffly that his aide, young Mr. Rowan, had after all been in the right. “‘Listen,’ Johnson said as he poked a finger into my chest. ‘You just go on standing up for what you believe . . . ‘” “‘Thank you, sir,'” Mr. Rowan says he replied. (“What a pity,” he writes of LBJ in a rare meditative moment. “A man so great in so many ways, and so mean and petty in others.” By contrast, Adlai Stevenson, who refused Rowan a car and driver during the latter’s brief stint at the United Nations, was well-meaning but unfit to be President for the unfortunate if plausible reason that he “lacked balls.”)

There follows an equally unlikely exchange the author supposedly had with President Reagan at a Gridiron dinner. Needless to say, the “actor-turned-rabble-rouser” gets the worst of it, and indeed is reduced to whimpering when his “glib cliches” prove futile against Mr. Rowan’s forthright eloquence:

Reagan: “I tried hard to win friendship among blacks, but I couldn’t do it. . . .”

Rowan: “And that’s why you went almost eight years refusing to talk to the acknowledged black leaders of America?”

Reagan: (now desperate): “They attacked me at the outset, so I said to hell with ’em.”

Rowan (firmly): “Sir, I’ve attacked you in my columns because I believe that any president of all the people must talk to all the people and their leaders.”

Reagan (after “a long pause”): “You know something? I should have talked to you seven years ago.”

Whether the leader of the Free World really fell silent on hearing Carl Rowan’s trite reformulation of Lincoln’s “of the people, by the people” speech, we can’t say for sure, but the pattern of all these exchanges never varies: Rowan is offended by some outrageous statement or insult about the poor and underprivileged, Rowan can stand it no longer. White Male cowers as Rowan delivers devastating reply—indeed, so devastating and eloquent that years later Rowan can reconstruct every word, objective, masterful, award-winning reporter that he is.

It was shortly after the Gridiron dinner that Mr. Rowan had that little incident for which, he says sorrowfully, he’ll long be remembered. As all the world would read, one night Mr. Rowan encountered an unclothed interloper and lady friend cavorting in his backyard pool. Seeing Rowan, the man charged, only to be laid low by Rowan’s unlicensed gun. It was only a wrist wound, but landed the pundit, a passionate gun-control advocate, in criminal court. Leave aside the details of that ridiculous episode, and just consider this complaint, which reveals a good deal about Carl Rowan’s world view: “The media staked out my house, hounding me everywhere, as though I had suddenly become some grotesque criminal. It was as if no one remembered, or gave a damn, that a few months earlier I was hosting the Ronald Reagans as president of the Gridiron Club. . . . “

Here the big columnist, champion of the poor and downtrodden, gets himself in a fix—and he wants to bring in the callous “actor-turned-rabble-rouser” as a character witness. Men have fallen from higher places than the presidency of the Gridiron Club, but one wonders what connection he saw between the dinner and the police investigation. What would he have expected officers on the scene to say—”Gee, Mr. Rowan, wish you’d mentioned that Gridiron affair with the Reagans earlier—we could have avoided this whole unpleasant business”?

That phrase above—the “acknowledged black leaders of America” with whom all Presidents must deal—just about sums up Mr. Rowan’s career path. From an early life of true privation, he emerged rightly defiant, but never quite shook off that “haughtiness.” He himself rose “on merit,” but then, with other Acknowledged Black Leaders, succumbed to the affirmative action temptation that would deny others, black and white, the same privilege while further empowering—Acknowledged Black Leaders. He dismisses scornfully the “glib cliches” of Republican white males, and of course their black “quislings” who feel insulted by quotas and timetables, in a memoir full of warnings to “lily-white” Republicans about “turning back the clock”—as if these inspired new phrases will surely silence those glib cliches.

Breaking Barriers is a testament to the capacity of a comfortable Capital pundit to become an unquestioned fixture indulged by publishers and public alike, trading, like his fellow acknowledged black leaders, on yesterday’s reputation, and more concerned with being “acknowledged” than with actually being a leader.

[Breaking Barriers: A Memoir, by Carl T. Rowan (New York: Little, Brown) 395 pp., $22.95]

Leave a Reply