The name Philip Larkin (1922-1985) is a wonderfully poetic one, conjuring an image of a lover of horses on a carefree adventure. Such, however, is far from the temperament of this 20th-century poet, whose poetry is more suggestive of some horse in a Dickens novel, harnessed to an industrial wheel and moving forever round in some dreary factory. Larkin believes that there is “no elsewhere that underwrites our existence.” His friend Kingsley Amis described him as “one who found the universe a bleak and hostile place and recognized very clearly the disagreeable realities of human life, above all the dreadful effects of time on all we have and are.”

Larkin’s sustained melodious song is of the endless passage of time and coming death. “Aubade,” which means a morning song, first appeared in the Times Literary Supplement during Advent 1977. It is an advent of death, not birth:

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light:

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Czeslaw Milosz appreciated the poetic skill and craftsmanship of Larkin’s five-stanza poem but protested that

the poem leaves me not only dissatisfied but indignant and I wonder why myself. Perhaps we forget too easily the centuries-old mutual hostility between reason, science and science-inspired philosophy on the one hand and poetry on the other? Perhaps the author of the poem went over to the side of the adversary and his ratiocination strikes me as a betrayal? For death in the poem is endowed with the supreme authority of Law and universal necessity, while man is reduced to nothing, to a bundle of perceptions, or even less, to an interchangeable statistical unit.

Larkin was strongly influenced by Thomas Hardy and writes with his hard clarity. Hardy’s poetry, however, is more open to the possibility of grace working through nature. Even Hardy hearing a “Darkling Thrush” holds open the possibility of “Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew / And I was unaware.” Ecstatic notes of optimism are not to be found in Larkin. Yet, in his Introduction to The Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century English Verse, Larkin says that he wanted “to bring together poems that will give pleasure to their readers.” This theme recurs in his essays. Larkin believed that poetry readers should “enjoy what they read,” wanting to know, “if not, what the point is of carrying on.”

I do not take much pleasure in the content of Larkin’s poems, but I do delight in his use of language and in a poetry that scans and rhymes and is coherent. These qualities are altogether rare today, but Larkin is a master of traditional verse: He suffers in perfect iambs. Larkin rightly took pleasure in the form of his poems. How he found pleasure in their burden, I have trouble fathoming.

I used to think Larkin was simply having a lark in his poems. Starting to laugh, however, I found that I could manage only a cynical smirk. He says children are mean and seems to think that love is just selfishness. Sadly, he never moves beyond this stance. Larkin’s is the antithesis of passion, for passion means “to let,” “to allow,” and it entails suffering. This pained suffering is part of a higher nature of which we are capable. Larkin closes himself to this mystery, thinking it “wiser to keep away.”

In “Love,” he writes that

The difficult part of love

Is being selfish enough,

Is having the blind persistence

To upset an existence

Just for your own sake

What cheek it must take.

Larkin never married. Of his parents’ union (which was not an unhappy one), he writes, “the marriage left me with two convictions: that human beings should not live together, and that children should be taken from their parents at an early age.” I find much of his poetry to be a kind of self-willed negativity and a closing off of oneself to the world. Larkin once said that “deprivation was for him what daffodils were for Wordsworth.”

Trying to put Larkin in perspective, I picked up The Soul of London by Ford Maddox Ford. The business of the artist, says Ford, “is to render the actual” and to be “passionately alive to all aspects of life” and open to it. For, in the modern world, “facts so innumerably beset us that the gatherer of facts is of little value.” The artist must make out the pattern of the bewildering carpet that modern life is. Larkin, while painting the pattern of the carpet, never looks beyond a factual world and so closes himself off in darkness.

Hardy once said that we should admit that we are in the dark, but that light may follow. Larkin seems to think the darkness has virtue in itself. In a review of “The Poetry of William Barnes,” he writes: “if his work has a deficiency, it is in lacking Hardy’s bitter and ironical despair. Barnes is almost too gentle, too submissive and forgiving.” One might ask, “Too submissive, gentle, and forgiving” to whom?

I prefer Larkin’s early poems, where a little light is allowed to shine, as in “Coming”:

On longer evenings,

Light chill and yellow,

Bathes the serene

Forehead of houses.

A thrush sings,

Laurel surrounded

In the deep bare garden,

Its fresh peeled voice

Astonishing the brickwork.

It will be spring soon

It will be spring soon-

And I whose childhood

Is a forgotten boredom,

Feel like a child

Who comes on a scene

Of adult reconciling,

And can understand nothing

But the usual laughter

And starts to be happy.

Though Larkin sees no order in the universe, he maintains an ordered integrity in his poetry and is a formidable defender of tradition. He loathes academic poets and their parlor games with prose that they call poetry. That is the curious thing about Larkin. This quotation from a Paris Review interview is uplifting:

It seems to me undeniable that up to this century literature used language in the way we all use it, painting represented what anyone with normal vision sees, and music was an affair of nice noises rather than nasty ones. The innovation of “modernism” in the arts consisted of doing the opposite. I don’t know why, I’m not a historian. You have to distinguish between things that seemed odd when they were new, but are now quite familiar, such as Ibsen and Wagner, and things that seemed crazy when they were new and seem crazy now like Finnegan’s Wake and Picasso.

This new edition reflects Larkin’s own ordering of the poems and also contains his previously uncollected work. The reader can see how great a master he is of traditional poetic form and how fully he paints the emptiness of modernity.

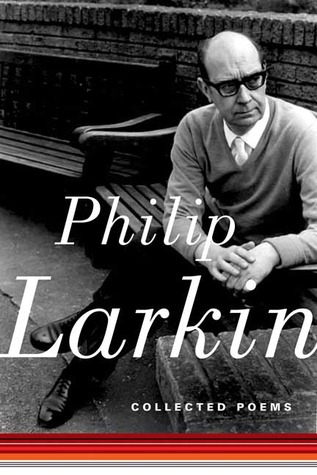

[Philip Larkin: Collected Poems, edited by Anthony Thwaite (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) 218 pp., $14.00]

Leave a Reply