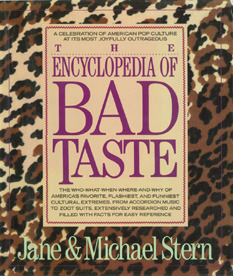

I suppose this book might be called a coffee-table book. It has the shape and the lavish illustration of that kind of thing. And I suppose that of its kind, this book isn’t so bad, which is not to say that it’s good.

The Sterns’ alphabetical survey of bad taste has the merit of some historical information. The background supplied for “Baton Twirling” was informative, for instance. So was the lowdown on “Breasts, Enormous,” “Hot Pants,” “Twinkles,” “Roller Derby,” and “Welk, Lawrence.” But there is a sense in which The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste is, like the bad taste it catalogues, sick, sentimental, trivializing, life-denying, and phony. A book about pornography or violence can seem as nasty as a book of pornography or violence—a point not lost on those who market such books. This book about bad taste is not going to be of consuming interest to those with good taste; rather, it will instruct those of debased standards on how to lower the level. Your surgeon should bone up on anatomy? But Jack the Ripper will read the book, too.

In their introduction, the Sterns try to take the high road. They begin by quoting Clement Greenberg on kitsch, but soon relapse to wallowing in the sleaze they know so well.

When things hang around this collective cultural Warehouse of the Damned long enough, they begin to shimmy with a kind of newfound energy and fascination. Their unvarnished awfulness starts looking fresh and fun and alluringly naughty. They grow beyond mere tastelessness and enter the pantheon of classic bad taste. . . . And isn’t that just grand! We hate to think how drab things would be without bad taste. It is a powerful seasoning; sometimes it is so spicy it makes you gag. But consider the alternative: a world without Roller Derby cross-body dunks, Las Vegas lounge acts, blubbering globules of Tammy Faye Bakker’s mascara, and the grandeur of Dolly Parton’s breasts. Life would be just too damn polite.

Maybe so; but I am not too polite to say that this meretricious volume is as vulgar as its subject, though less honest. The authors seem to have been confused by their obsession with slime, and so their book is flawed by the corrupting effect of their subject. The cornball and the cutesy-poo have a way of dominating their own exposure.

Though the Sterns go on about “history,” their book has little sense of moral, not to mention aesthetic, perspective. “Bad taste” is endowed with an aura of nostalgia, and somehow becomes good—or at least collectible. The Sterns fail to give us a strong enough sense of shadow, of Original Sin, of speckled human nature, a feeling that “bad taste leads to crime.” Great literary passages about bad taste always give us that awareness, as well as amusing us superficially. I refer to Chapter 17 of Huckleberry Finn, parts of The Great Gatsby, passages of Lolita, and much of the fiction of Flannery O’Connor. What—considering the blighted environment and the helpful bookshelf—do we need the Sterns for?

This account of bad taste not only lacks depth, it lacks breadth—and for an “encyclopedia,” that is damning. Anyone could think of scores of obvious and gross examples of bad taste omitted from this account: chewing gum is one. Television is another. Various advertisements, foods, articles of dress—take your pick. But even if the coverage were doubled, the campy attitude and shallow view would still cripple a book hobbled by a highly selective field of choice. There is a pattern of selection and exclusion that might be called “political,” for want of a better term.

I think that the Sterns’ list of distasteful items and people and places represents an upper-middle-class view of the lower-middle class, and even an Eastern view of the Heartland and the Bible Belt. I find it bizarre that they have included the Smoky Mountains—but not New York City. I find it perverse that they have cited Las Vegas—but not Massachusetts. I find it weird that they have singled out Charo, Liberace, and Dolly Parton—but not Senator Kennedy, Bishop Spong, or Dr. Ruth.

The Sterns are not about to mock the sordid icons of the privileged. “Civil rights,” “socialism,” “multiculturalism,” and “Washington, D.C.” are absent from their litany. “Vans” are amusing, but imported luxury sedans are sacrosanct. “Cool Whip,” “Hawaiian Shirts,” and “Spam” rate a sneer, but there’s no mention of alfalfa sprouts, the garment industry, or designer water.

The Sterns take the easy way out. As far as “bad taste” is concerned, they have it both ways. Either it’s cute, or it’s for bumpkins. If it’s bad, it’s not here. Wonder Bread may not be nourishing, but it won’t kill anybody. I looked in vain for something in bad taste that was actually a problem, a real threat, like sodomy, drugs, or abortion. I don’t say that “Cedar Souvenirs” are in good taste, but they aren’t a menace to civilization.

Hamburger Helper is a symptom, not a cause. Rabid marketing schemes and industrial ugliness are—sad to say—at the heart of our economy. The mythical right to be wrong is part of the American Dream. So—here we are. To study bad taste is to look in the national mirror. These authors averted their eyes from the big picture, and blinked at the most revelatory implications of bad taste.

But one good thing about their Bad Taste is that, though they omitted Oprah Winfrey, Kitty Dukakis, and Phil Donohue, the dust jacket does feature a picture of Jane and Michael Stern.

[The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste, by Jane and Michael Stern (New York: HarperCollins) 335 pp., $29.99]

Leave a Reply