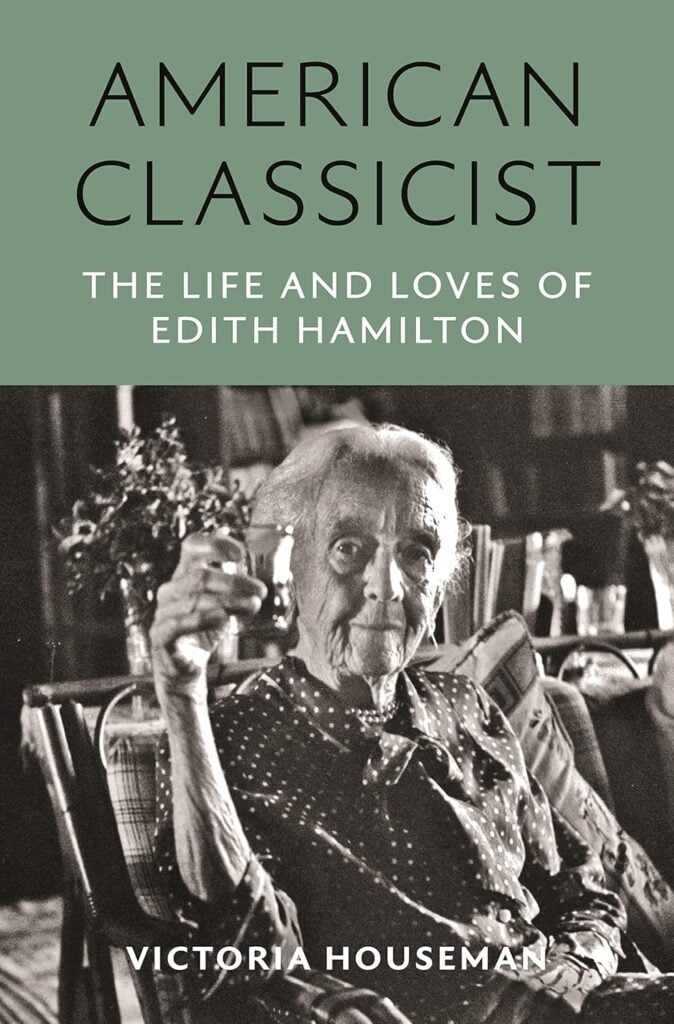

American Classicist: The Life and Loves of Edith Hamilton

by Victoria Houseman

Princeton University Press

528 pp., $39.95

Classical and liberal arts education have resurged during the last 20 years, especially at the primary and secondary levels. Parents and educators seek something different from the reigning educational establishment, which has held sway for much of the 20th and 21st centuries. Indeed, they are looking for something that answers the questions that have vexed human beings since their beginnings: “Who am I?,” “Where am I going?,” “Why am I here?,” and “How ought I live?”

In addition to the establishment of new schools, new organizations dedicated to classical learning or the traditional liberal arts are making inroads into the broader educational discourse in America. There is no greater evidence of the impact of this movement than the vitriol with which teachers’ unions and progressive “educrats” rail against classical charter schools and the movement in general. These levelers follow the lead of their sage, the misguided educational reformer John Dewey. Paraphrasing an early critic of Dewey’s approach, his followers “make dogmatic statements without proof and then tear down the opposition by calling them names.”

Among the pantheon of greats who continue to inspire the classical education movement is the American classicist, teacher, headmistress, author, translator, and raconteur, Edith Hamilton. This brilliant woman, who began life in upper middle-class circumstances in Fort Wayne, Indiana, was first renowned in progressive artistic circles; later in life she would move politically to the right, where her writing on the classical foundations of the American republic would be embraced by politicians of the Old Right. Her 1942 book Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes is still recognized as a key book in the renaissance of classical education in America.

Victoria Houseman, in her new book examining the life of Edith Hamilton, American Classicist, does a thorough job in telling the story of this important figure. Houseman, a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, states the purpose of her biography is to “place Edith Hamilton’s books in their proper historical context and to examine how her life experiences informed her works.” In addition, her work fills a glaring lacuna: it is the first definitive biography of this deserving scholar.

Houseman begins by telling the story of Hamilton’s initially comfortable upbringing in the Midwest, the fall of her family’s financial fortunes, and her matriculation at Bryn Mawr College. Having begun her study of Latin at a very early age, Hamilton later grew closer to Greek and was naturally drawn to the curriculum at Bryn Mawr. Newly established as a college for women, Bryn Mawr would become a distinguished and academically rigorous center for classical learning. Students of classics in the United States would readily recognize the names of Hamilton’s professors and mentors: Basil L. Gildersleeve, Gonzalez Lodge, and Herbert Weir Smyth, among others.

In addition to studying classics, Hamilton fell under the influence of scholars who would influence her thought throughout her nearly century-long life. Prominent among them were Oxford don Matthew Arnold and Scottish philosopher Edward Caird.

Arnold believed the roots of Western civilization were anchored in the ancient worlds of Greece and Israel. The enduring relevance of Hellenism and Hebraism made their study critical to solving contemporary problems, a theme that would recur in Hamilton’s oeuvre.

Caird was a philosopher of the British Idealist school that developed in the late 19th century. His thought was a rather eclectic amalgam that drew inspiration from Plato and Hegel. For Caird, religion is “consciousness of a divine presence and manifested itself as an individual’s attitude toward their place in the universe.” Accordingly, individuals were to “make the most out of their reason and fully realize their potential through social service.” Caird would remain a seminal influence on Hamilton’s thought and would account for her very unorthodox version of Christianity, based on Caird’s attempt to integrate Hegelian thought with traditional Protestantism. His, and Hamilton’s, was a sort of religious idealism rather than one based on creedal belief.

After studies at Bryn Mawr, Hamilton studied at the University of Leipzig and the University of Munich before returning to the United States, where she assumed the position of headmistress of the Bryn Mawr School, a girls preparatory school in Baltimore that was a feeder to the college. She remained headmistress from 1896 to 1922, and once grumbled that the role “does tire the mind without giving it any food, and that is the sad part of it.”

Hamilton also understood well the role of politics among board members, school administrators, and parents. In confirmation of the adage that “the more things change the more they stay the same,” she lamented that parents were not more discreet with their criticisms of the school administration in the presence of their children. “It seems to me rather a pity that the children should be so intimately acquainted with the workings of the school,” she said.

Despite the challenge of managing the school, Hamilton still managed to cultivate her intellectual and social interests. She befriended some of the more progressive intelligentsia of the era, among whom were Bertrand Russell and Gertrude Stein. She supported some progressive causes but also engaged in intellectual battle against progressives who questioned the relevance or usefulness of the classics in secondary girls’ education. What emerges is a woman who is not easily categorized. While she supported women’s suffrage and compulsory education laws, she argued vehemently against progressive “reforms” that would have abandoned the teaching of Latin and Greek.

After retirement in 1922, she finally found time to “feed the mind” in a second, late career as a translator and writer. Demosthenes once said, “the time for extracting a lesson from history is ever at hand for them who are wise.” This is a fitting encomium for Edith Hamilton in the last 40 years of her long life. She wrote books that brought knowledge of the classical world to a new generation, with the conviction that the ancients had something to say about contemporary problems. Those problems, including the Great Depression, two World Wars, the Space Race, and the Cold War, colored her works on ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Roman civilization.

Hamilton’s writing was not just the work of a populizer of ancient thought, but rather of a pedagogue who wished to preserve an American culture that was made possible by these ancient antecedents. While unorthodox—especially in her theology—she was convinced that the West was created by the genius of Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem and was worth preserving.

Despite her early flirtations with progressives, Hamilton’s work and ideas eventually moved her toward conservative politics. She befriended Ohio Senator Robert Taft and supported politicians who promoted the virtues of the old republic, as opposed to the emerging centralized, hegemonic American state.

Professor Houseman’s biography is as extensive as it is magisterial. A very fine bibliography, index, notes, and appendix of Edith Hamilton’s friends and colleagues will make this volume a standard reference for future scholars. Deficiencies, however, are also present. There are more than a few overly deferential notes of political correctness and unnecessary acknowledgments of imagined civil rights struggles, which should embarrass the author.

In addition, while Houseman does focus more on the intellectual contours of Hamilton’s thought, her painstaking and voluminous examination of Hamilton’s extensive network of familial and personal relationships is exhausting. It also seems to be motivated by Houseman’s desire to imply that Hamilton was a closeted homosexual. Hamilton had a longtime companion and partner, Doris Fielding Reid, a relationship to which Houseman devotes many pages. While their relationship was unconventional by most standards, it seems that Houseman is preoccupied with the notion, if not pursuing her own cultural and political agenda.

Even when the author is not prying into Hamilton’s sexuality, all the detail verges on the extraneous. I cannot help but echo the sentiment Evelyn Waugh expressed when commenting on a biography of a popular English author, which “gives details of every chop he ever ate & every speech at every public banquet.”

The aims and purpose of education preoccupied Hamilton during her final years. She saw that the ideological need to defeat political foes often drove the utilitarian and pragmatic approaches of modern education. Hamilton prescribed the classics as a remedy. “Only the study of the ancient languages … produced the clarity of mind needed to meet the challenges of the Cold War world,” she wrote, “including the maintenance of political freedom.”

The challenges have only increased since her death in 1963. I believe that the resurgence of a classically trained and self-controlled citizenry will be the last best hope for the maintenance of our republic. Edith Hamilton would agree.

Leave a Reply