A Continent Erupts: Decolonization,

Civil War, and Massacre in Postwar Asia, 1945-1955

by Ronald H. Spector

W. W. Norton

560 pp., $40.00

This excellent account of East and Southeast Asia in the 10 years after the end of World War II is a follow-up to Spector’s earlier work, In the Ruins of Empire, which dealt with the immediate aftermath of Japan’s surrender. It is blunt, honest, often unpleasant, and, at least by contemporary standards, sometimes politically incorrect in its implications and judgments.

The period of decolonization was not one of a simple fight between justice and injustice, or against “white supremacy” or Western imperialism, nor was there a clear-cut conflict between Communist and anti-Communists. Nor were the regions involved “dragged” into the Cold War. Rather, the Cold War was, as Spector puts it, “invited in.” Struggles for independence were crisscrossed by fighting about who would rule after the old masters left. Many minority ethnic groups believed with good reason that their European rulers had protected them against persecution and worse by the ethnic and religious majority.

Spector concentrates overwhelmingly on events in China, Korea, Indonesia and Vietnam. Although he does not deal with Burma, Malaya, or the Philippines, developments in those countries, and those of South Asia, offer close parallels showing how postcolonial nations are often riven by ethnic conflict. It is a striking fact that the Muslim Moros of the southern Philippines were sorry to see the Americans leave, regarding them as a shield against the Christian Filipinos—even though few Americans liked the Moros, preferring instead the Christian majority of their subjects. The hatreds between local peoples were often more ferocious, and longer lasting, than their distaste for their Western masters.

Spector is very good in dealing with the attempts of the French and Dutch to regain their Southeast Asian possessions; perhaps he is a little more favorable—or at least a bit less unfavorable—to their efforts than has been fashionable, though they hardly come off well. Not only they, but other Westerners, arrived after V-J Day with no comprehension of the changes that had taken place under Japanese rule and during the interval before the forces of Admiral Mountbatten’s Southeast Asia Command reached Vietnam and Java. It was assumed that the peoples involved were basically passive, and would accept the return of the French and Dutch.

The Americans were little better, having assumed that the problem would be to get diehard imperialists to “grant” independence, or a definite promise of it. No one envisioned the situation that actually developed as already-established Southeast Asian national governments faced European reconquest. Though they had a low opinion of the French, the Americans had been fooled well before the war by the Dutch government and its intelligence agencies—who seem to have had skills the fabled Nigerian conmen might envy—into thinking that Dutch rule was much better, and far more popular, than it really was.

Indonesia’s war of independence has attracted far less attention than the war in Indochina, although Indonesia is a vastly more important and richer country, with the second largest population then under European rule. Early on, the war in Indonesia was marked by brutal violence not only against the Dutch civilians who had been interned by the Japanese, but also against Eurasians, Indonesian Christians, and the Chinese and other minorities.

Although most Indonesians were not religious fanatics, religious difference played a significant role in the war. Spector is commendably frank about this, much in contrast with the traditional standard account, George Kahin’s Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia.

Spector makes clear that while the Dutch contempt for the Indonesian nationalists was not entirely baseless, their attempt to regain control was hopeless. They set themselves an impossible task. They routinely defeated the Indonesian nationalist regulars but were utterly unable to cope with the guerrillas behind their front lines, or to prevent them from wrecking the economy of the Dutch-occupied areas. This is a striking parallel with what happened in northern Vietnam, although Ho Chi Minh was, thanks to Chinese help, much more successful at building an effective conventional army than the Indonesians. There is no blather in Spector’s account, unlike many others, about Ho as the Vietnamese George Washington. Ho was an exceedingly capable and ruthless leader, whose efforts in 1945 and 1946 were primarily devoted to crushing the non-Communist Vietnamese nationalists.

Neither the Dutch nor the French showed much political sense at any point. The French and American attempt to make use of the Vietnamese Emperor, Bảo Ðại, may have been even more misguided than Spector suggests. Aside from the folly of relying on a single individual instead of a program—a mistake made by Americans in dealing with other countries, again and again—Bảo Ðại was an out-and-out scoundrel. The Americans were deluded in thinking that they could rely on Bảo Ðại and the non-Communist nationalists—whom the French had reluctantly allied with in 1949—in a struggle against the Communists.

Equally mistaken was the Eisenhower administration’s hope that the French would keep fighting and achieve victory. This had no basis given French public opinion, which by 1953 was overwhelmingly opposed to the war and unwilling to carry on. Whatever the French leaders led the Americans to believe, they had no hope of doing more than getting some sort of stalemate and negotiated ceasefire.

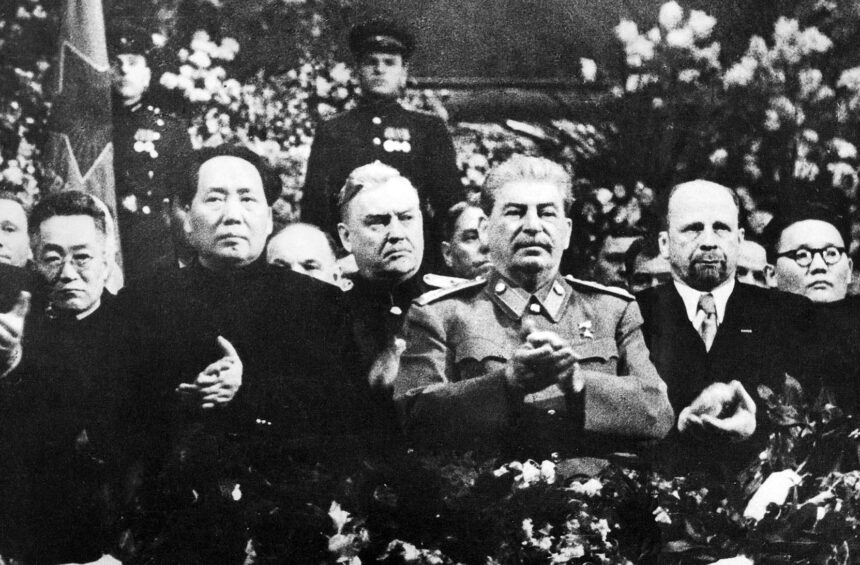

The final phases of the Chinese Civil War and the Korean War posed larger problems. Spector provides an excellent account and explanation for the Communist victory in China. He perhaps inadvertently understates the effect of Soviet help to the Chinese Communists in Manchuria, and he is not entirely accurate in his understanding of the zigzags in Soviet policy there.

The Soviet alternation between active aid and passive indifference to Chinese Communist efforts seems to be better explained as a result of Stalin’s wavering between worrying about what the Americans would do and confidently assuming that they would not react dangerously to his actions. For about three to four weeks after Hiroshima, Stalin drew in his horns, fearing the Americans’ next move. He at least pretended greater moderation in East Central Europe, canceled the planned invasion of northern Japan, and readily agreed to the American proposal to divide Korea into occupation zones. Realizing later that he had been excessively worried, he returned to a more aggressive line.

Although Korea had of course been a Japanese colony, the Korean War does not fit as well into the narrative of decolonization. But Spector’s account is quite good. The American occupation of South Korea began in a state of ignorance comparable to that of the Western powers in Southeast Asia and was never very well conducted. It is not a very inspiring story, nor is the rise of South Korean President Syngman Rhee nor the early history of the Republic of Korea. It is probably an exaggeration to suggest that Rhee was effectively a dictator before the Korean War. He (or the clique manipulating him) did not manage to achieve that until 1952.

Spector is better on the Korean War itself, although his account will certainly not please General Douglas MacArthur’s uncritical admirers. Apart from criticizing MacArthur’s handling of the offensive in North Korea and underestimation of the Chinese in the fall of 1950, Spector strongly implies that the famed Inchon landing only succeeded because Kim Il Sung insanely ignored Chinese advice that it was a likely move, and denied even the possibility of a serious American counterattack.

Spector is even less complimentary of MacArthur’s staff, notably the pandering Chief of Intelligence Charles Willoughby and Chief of Staff Edward Almond, who later commanded X Corps in Korea. He may be a little unfair to Almond, who was certainly an erratic and not very likable character (though MacArthur’s successor, General Ridgway, thought a lot of him), but it is true that MacArthur notoriously surrounded himself with yes-men.

On the other hand, Spector pays more attention to, and is more sympathetic toward, the ROK Army than are most American accounts. He perhaps underplays the importance of the air war, but that is a judgment call. Interestingly, he cites evidence that the Chinese were more ready to intervene in the Korean War earlier than has been previously supposed, as early as July 1950, but Stalin and Kim Il Sung did not want that.

This view reinforces the likelihood that Mao was quite ready to take an aggressive line all along. For him, although probably not for other Chinese leaders, the aim at least until May 1951 was to gain all of Korea, not just to preserve North Korea from liberation when the North Korean invasion backfired. Even after that, when armistice talks were under way in August 1951, Mao told Stalin that he regarded an armistice as just a truce lasting a few years, after which the Communist side should

resume the war!

Leave a Reply