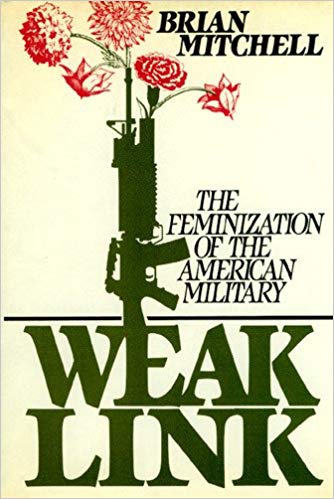

The feminist century—ours—is markedly different from any period known . . . I was going to say “to man” but perhaps we don’t talk that way anymore. Events have transformed the relationship of the sexes from one in which men occupied most leadership roles to one in which women make laws, minister the sacraments, and direct corporate takeovers. Over the past twenty years, landmarks have been swallowed up. The terrain is dreamlike: familiar in its own way, and yet shrouded in mist. So quickly have the changes come, so broadly, and deeply have they penetrated society, that we cannot completely comprehend what has been happening. It still startles, for instance, to happen on a book jacket bearing a title like Weak Link: The Feminization of the American Military. We all know that for the past couple of decades there have been women in all branches of the military service, but we did not know—perhaps had not even thought to wonder—whether the basic meaning of military service had changed.

We know in our hips, to borrow from Willmoore Kendall, that war is about death and suffering and heroism and that none of this will be different short of the Second Coming. Thus we assume that the military, in assimilating women into its ranks, requires that they live up to the masculine requirements of strength and bravery. The thesis of Brian Mitchell’s valorous book—I’ll be surprised if he isn’t lynched on account of it—is that the military has failed to keep in mind these realities: that it has downgraded performance standards in the name of equal job opportunity; that it is building a kinder, gentler military that may or may not pass the next test it faces.

As recently as 1986, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of the Army, John O. Marsh, Jr., asserted that modern military values mirror “the ethic of our people which denies any assertive national power doctrine and projects a love and mercy to all.” Love! Mercy! A fine theological duo, certainly, but the Army is not a seminary. The human consensus, from Homer to Patton, is that the army’s job is unlovingly to stomp the bejesus out of the enemy.

Soldiering-as-a-man’s-job is one of those antique prejudices we are instructed to shed in the last decade of the feminist century: the military bureaucracy seems to have shed it almost completely. If you wonder how soldiers can assert unsoldierly things, remember who appropriates the money the military spends. Congress. Congress is dominated by political, ah, leaders dependent on the support of the feminist lobby. The military knows on what side its bread is buttered. “Personnel,” writes Mitchell, who is a reporter for the Navy Times and a former infantry officer, “are required to attend equal opportunity training during which EO officers preach the sanctity of sexual equality and the folly and immorality of belief in traditional sex roles. The definition of sexual harassment has expanded to include the open expression of opposition to women in the military. Officers and senior enlisteds are kept in check by their performance reports; a ‘ding’ in the block that reads ‘Support Equal Opportunity’ can have career-ending consequences.”

The military still resists the introduction of women into combat but has so narrowed the definition of “combat” that many female soldiers would be caught up in the shooting should war actually come. Meanwhile, the sisterhood continues to campaign.in behalf of the right of sisters to go into combat, from which the patriarchy has so far excluded them. The question of male-female roles is one that society, out of embarrassment, hesitates to wrestle with. To raise it at all is to acknowledge archaic patterns of thought. Feminist successes in sweeping aside employment barriers have conditioned us to believe that, for professional purposes anyway, men and women are interchangeable units. If a man can string telephone wires or sew sutures, so can a woman.

The Pope finds that fewer and fewer Roman Catholics listen patiently to explanations of why all priests are male. (In the American Communion they no longer are.) “Come on,” say advanced spirits, “what do you mean a woman can’t say words over some bread and some wine, same as a man can say them?” The priesthood has become another affirmative action frontier, along whose borders impatient caravans are camped, awaiting only the signal to enter. The military is not unlike the priesthood in that it is a sexual vocation—of secular, not theological, character. Men are soldiers for self-evident reasons, such as aggressiveness and upper-body strength (simply to leap from a foxhole, carrying a rifle, takes muscle).

History shows forth a few—a very few—female military leaders, like Boadicea and Zenobia, but no feminized armies at all. The Amazons never existed, and the Israelis, contrary to a familiar fabrication, employ military women largely as clerks, typists, nurses, and so on. Never do Israeli women go into combat.

On what grounds, then, do we challenge the concept of the man as warrior, the woman as tender of the home fires? Ideological grounds, of course: what women want, and these days it is a lot they want. Actually, as Mitchell shows, feminists have divided motives in seeking to integrate the military. Some want to show they’re as tough and hard-bitten as any man (though few if any have achieved this). Others want to sensitize the warmaking profession, to make it more tender, more egalitarian, more pacifistic, of all things. The Army’s male adjutant general recently expressed the pious hope that among American warriors there would grow “sensitivity toward and more caring for one another.”

The net result is the same . . . the sanding down of rough male edges, the softening of tone and substance. Veterans historically like to sentimentalize the Old Army, or the Old Navy, where things were rougher arid tougher than today. Well, this time they’re right. Standards have been scaled down sharply to accommodate those otherwise unable to meet them.

Women have, to begin with, only 80 percent of men’s overall strength. During 1980 tests at West Point the work of male cadets exceeded that of female ones by 48 percent at the leg press and 473 percent at the bench press. “All of the services,” Mitchell writes, “have double standards for men and women on all the events of their regular physical fitness tests . . . In the Army, the youngest women are given an extra three minutes to complete a two-mile run.” Additionally, women are hospitalized three times as often as men. They are unavailable for duty from two to two-and-a-half times as often as men. They leave the military at a higher rate than men, and up to 17 percent are pregnant in any given year. Eleven percent, being single parents, must worry about child care. What we have on this sad showing is a military establishment significantly less prepared to defend the country than an all-male military of comparable size.

Just here the eyes and the mind start to roll in concert. It is like standing in front of a funhouse mirror. Everything is wavy. The question before us is life and freedom, not employment opportunity, yet opportunity is the only consideration that seems to matter when the topic is military women. Feminism-in-fatigues is the last laugh of that egalitarianism spawned by the French Revolution two hundred years ago. At this point—the point at which we assert that a female soldier is the same as a male soldier—all is reduced to absurdity.

The complementarity and mutuality of the sexes is not what we talk about anymore . . . the role of this one, the role of that one. We talk about interchangeableness, even when we know (or should know) interchangeableness to be a lie. History instructs us as to the martial nature of the male; but it teaches an even harder lesson, which is that social arrangements built on lies are not long for this world. Things are as they are; they are not necessarily as the silver-tongued and nimble-brained would like them.

Feminists now seeking to repeal the law barring women from combat are in reality trying to repeal the laws of nature. These, unlike acts of Congress, are unrepealable, but nonetheless various women won’t be happy until fellow women can get blown apart by artillery shells, just like men. How’s that for love, compassion, equality, and the rest of that good 20th-century stuff?

[Weak Link: The Feminization of the American Military, by Brian Mitchell (Chicago & Washington: Regnery Gateway) 232 pp., $17.95]

Leave a Reply