Because I well remember reading some of the pieces Mary Gordon has assembled here, I had no reason to wish to reread them and no cause to want to read the ones I’d been lucky to miss the first time around. What I think about Mary Gordon’s writing reminds me of a favorite malapropism: “Do I have to spell it out for you in four-letter words?”

The first thing that disgusts me about Mary Gordon’s literary screeds is their phony tone. Her “voice”—because she hasn’t really got one—is a chalksqueak of false notes. She sounds like a feminist drug addict who overdosed on Virginia Woolf, with the result that everything annoying in the arch breathlessness of Bloomsburian preciosity is magnified. Reading Mary Gordon is exhausting, because of all the cringes she provokes. The repeated use of “one,” to cite an example—the third person substituting for the first and second—isn’t American usage, but the artsy-craftsy hoity-toitiness makes for a “literary” air, does it not? “If only one had the Ford of A Man Could Stand Up at one’s side to tell one, in the most beautiful sentences imaginable, why men need women and women need men!” Oh yeah? If only one had the Benny Hill of the syndicated TV show to demonstrate to one, in the rudest way conceivable, why one doesn’t need Mary Gordon for anything, then one’s feelings (those little dears) would be ever so gratified! And perhaps then one would not so often feel, as, reading these pages, one often does, that one was watching a Girl Scout try to walk in her first pair of high heels.

The load of tea-and-crumpets-with-Virginia-Woolf codswallop takes many forms, but I think is only a symptom of a more fundamental imposture. She is always carrying on about being an “artist,” a “writer,” a “writer-artist,” and a “novelist.” When one considers her latest novel, The Other Side, such hauteur seems preposterous. Trying to sound like Henry James writing his prefaces is, after all, not recommended to anyone who is not Henry James. Quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi.

Mary Gordon’s vindictive, even nasty essay, “‘I Can’t Stand Your Books’: A Writer Goes Home,” is a highly revealing and instructive document. She has insisted here on an attempt to embarrass various relatives for having, at a family funeral, intimated to her their dislike of her writing. Even the deceased, her uncle—a supporter of the ERA!—had not approved of her work. But there is noble Mary—”I held my baby son in my arms and wept . . . I walked with my infant son . . . “who survives this episode to publish her contempt for her family, and to reveal what has long been obvious; she despises the Irish-American Catholics whom she affects to write about. She doesn’t understand them or sympathize with them; I don’t believe she even knows them. Mary Gordon is brazen in announcing her superiority to the community of which she is the self-appointed spokesperson.

To think of oneself as a writer of literature rather than a journalist or a popular writer, one must think of oneself as a citizen of a larger world. By this I do not mean that one necessarily defines oneself as outside the community—my own prejudice is that to lose the identification with the small community is to lose irreplaceable riches. But if one is going to think of oneself as a writer-artist, one must think of oneself as in the company of other great artists. Artists who will not come from one’s own community, who have lived in different ages, spoken different languages, written about people who exist only because these writers have preserved their lives. And if one is a writer whose early years were formed in a small, closed community, one must have the courage to understand that it is outside the community that one may very likely find the people who will be the audience for one’s work.

Mary Gordon’s audience is outside the community that she rejected, but that mustn’t dare to reject her. She is one with Dante and Michelangelo, a legend in her own mind. Meanwhile, a fine writer such as Maureen Howard—who covers most of Gordon’s fictional territory—is neglected, I daresay because she is not politically correct.

Even by Gordon’s standards, her “Parts of a Journal” seem moronic, if not a parody by Woody Allen; her “Some Things I Saw” a mistake; and her “The Gospel According to Saint Mark” a presumptuous fiasco. But since qualitative distinctions are finally inappropriate in this vicinity, I want to conclude with some citations of fact. Mary Gordon to the contrary, Flannery O’Connor did not “contract” her fatal disease. She was not born in Milledgeville, Georgia. She did not discover that she was sick, as Gordon implies, and then return to Georgia, but rather discovered it visiting there and was unable to leave. O’Connor’s reputation does not largely rest on her posthumous collection of short stories; Cecil Dawkins’s first name is not Cecile. Get the picture?

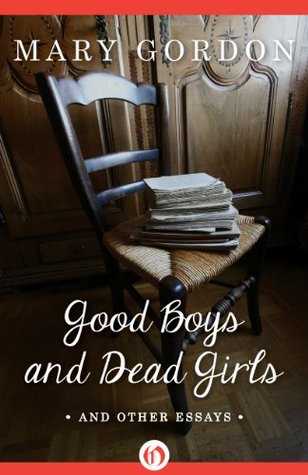

In sum, Good Boys and Dead Girls is the expression of the kind of mind that would declare, “O’Connor’s face was a peculiar one for a writer. . . . [I]t is a face from the provinces. . . . It is a face untouched by sexual experience or curiosity, which is why, perhaps, it seems not one of our own.” The snooty coarseness of Mary Gordon prompts me finally to observe that her photo on the dust jacket shows a face that, as H.L. Mencken said, makes you want to burn every bed in America. It is a face unshaded by sense or scruple, one that in former and better times might have caused its possessor to be left out on a cold mountainside to be devoured by wolves. Today, though, the most one can hope for would be the unlikely event of an uncomplimentary review; but, as Fats Waller used to say, “One never knows—do one?”

[Good Boys and Dead Girls: And Other Essays, by Mary Gordon (New York: Viking) 253 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply