Collected here are 159 of E.B. White’s short pieces written for the New Yorker. They show White at his best: as critic, essayist, humorist, and satirist. Though he will perhaps best be remembered for Charlotte’s Web and the Elements of Style, these slices of life on everything from lipstick to atomic weaponry remind us of White’s talent as a cultural critic.

Rebecca Dale has divided the material into such subjects as liberty. New York, nature, and inventions, and within each section the chronological arrangement allows the reader to witness not only the development of White as a thinker, from his rather whimsical and flippant commentaries of the 1920’s to his weightier pieces of the 1950’s and 60’s, but the increasing refinement of his impeccable prose.

It is in his roles as raconteur, as pithy observer of life, and as an enemy of cant that White’s abilities shine brightest. We are shown White the individualist who, in an essay that is as pertinent today as it was when he wrote it in 1938, argued that government funding for the arts “assumes, among other things, that art is recognizable in embryo—or at least recognizable enough to make it worth the public’s while to pay for raising the baby. And it assumes that artists, like chickens, are responsive to proper diet.” There is White the freethinker who, in commenting on a newspaperman’s concern for what today would be called “political correctness,” wrote that “under such conditions, the fourth estate becomes a mere parody of the human intelligence, and had best be turned over to bright birds with split tongues or to monkeys who can make change.” And there is White the social critic who mocked the childcentric nature of our culture. Lindbergh’s true accomplishment was not completing the trip, argued White, but that he accomplished his feat “without saying that he did it for the kiddies.”

There is also White the meticulous draftsman, the grammatical purist, for whom the Constitution could not possibly have been written “to form a more perfect union,” for whom an advertisement’s promise to keep lips looking “ravishing yet virginal” left him wondering whether the manufacturer wanted ladies “to be ravished, or does he want them to remain virgins?” There is White the eternal optimist who, in a story seemingly about the dangers of poisonous bulbs and seeds, reminds his reader that “we must plant this garden anyway.” And there is White the staunch protector of personal privacy. Though Dale gives ample examples of this side to White, all pale before his gallant stance against the 1940 census in a piece written for Harper’s: “Nobody looks forward with any pleasure to answering questions about his income or his bathtub. Privacy, the abstract blessing, is a lot bigger than the average-sized tub. And, like a tub, it can be irreparably marred by a blow from a blunt instrument, or law.”

Despite his many virtues as a social critic. White was an orthodox liberal who embraced the fashionable causes of his day, particularly world government. Like so many of his contemporaries, White saw little hope for humanity without a new international order to deal with the new science of destruction. He held high hopes for the United Nations, and even covered the Dumbarton Oaks Conference for the New Yorker in 1944, but he was not blind to the organization’s weakness or to the rivalries that continued between national delegates. He even suggested that the proposed location for the U.N. be changed from New York to Dinosaur Park, “so that earnest statesmen, glancing up from their secret instructions from the home office, may gaze out upon the prehistoric sovereigns who kept on fighting one another until they perished from the earth.”

In the end, however, it is White’s witty humor that rises’ to the top. Regarding the rumble seat in one of White’s first cars, “the only lady who ever ventured into the rumble skinned her right knee getting in and her left knee getting out, thus preserving a kind of rough symmetry through it all.” Regarding the 1944 invention of revolving doors with electronic eyes that determined “the right moment” for the door to begin moving, “an electric eye for a revolving door would need to be fitted with bifocals, because one person’s right moment is another person’s Dunkirk.” And what about the Soviet Union’s decision in 1957 to send a dog into space, to check the animal’s pulse, among other things? Well, white’s dead dachshund Fred, whose ghost frequently visited White, told the writer that no dog would fritter away time on such tricks: “A dog’s curiosity leads him into pretty country and toward predictable trouble, such as a porcupine quill in the nose. Man’s curiosity has led finally to outer space where rabbits are as scarce as gravity. Well, you fellows can have outer space. You may eventually get a quill in the nose from some hedgehog of your own manufacture, but I don’t envy you the chase. So long, old Master. Dream your fevered dreams!”

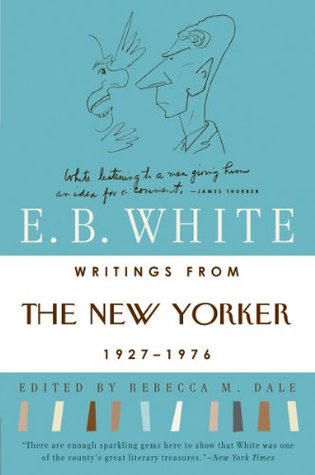

[E.B. White: Writings From The New Yorker, 1925-1976, Edited by Rebecca M. Dale (New York: HarperCollins) 244 pages, $20.00]

Leave a Reply