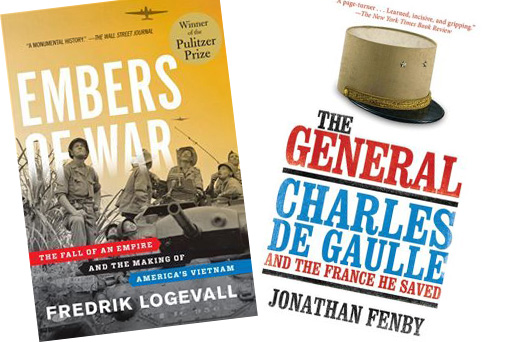

These books on postwar French history are meritorious and complementary. Professor Logevall’s effort is a careful military and political history of the French Indo-Chinese war, including three chapters on its aftermath. Mr. Fenby’s readable biography discusses the major events in De Gaulle’s life and supplies a good introduction to it for the uninitiated.

Both books have defects. Logevall’s discussion of the transition to American involvement has a rushed quality about it and does not fully mine the available materials. Fenby portrays De Gaulle as more a man of action than a man of thought, depicts him as time-bound and in some ways anachronistic, and undervalues his intellectual depth while devoting insufficient attention to his considered views as expressed in his writings.

Professor Logevall discusses the Vichy relationship with the Japanese, the ensuing British and Chinese involvement, and the re-entry of the French military and the disastrous bombardment of Haiphong. His book would have benefited from a fuller exploration of the pre-war experience, the Vietnamese economy, and the achievements and defects of French colonial administration. It also suffers from insufficient focus on the differences in attitude between the Catholic and Buddhist religious communities, though these were less significant during the French war than they became afterward. The migration of nearly a million Christian North Vietnamese to the South with American assistance after the Geneva Agreement was a critical event determining much that followed; as the commonsensical Sen. George Aiken put it,

when they got there, we felt responsible for their welfare, and that responsibility led to our involvement in the Vietnam War, which lasted for ten years. This was just another example of the saying that “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions.”

The Diem regime, installed by the Americans over the objections of the French, was a Catholic regime in its personnel and was viewed with hostility or neutrality by the Buddhists, at least until the massacres accompanying the temporary occupation of the city of Hue by the North Vietnamese at the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968.

Professor Logevall does not speculate on what might have happened had the French been successful in installing their preferred candidate Nguyen Van Tam, who had previously served as prime minister under Bao Dai and who, although a Francophile, had nationalist credentials. This event was narrowly prevented by heavy pressure from the Americans. The French vision of Vietnam’s future would have been strongly influenced by the Buddhist sects, and might have preserved at least Cochin China from North Vietnamese control. William Gibson, the former American consul in Hanoi, expressed skepticism about Diem before his installation; so did French Deputy High Commissioner Jean Daridan and the hawkish American commentator Joseph Alsop.

Nor does Logevall discuss the failure of the Americans and French to press for a straightforward partition agreement, similar to the Korean one, at the time of the Geneva Conference. Both in Geneva in 1955 and in Paris in 1973, the provisions made for future unification helped doom any hope of a stable solution, and in both cases provided for a withdrawal of Western forces unaccompanied by any mutual-defense agreement such as the Korean agreement extracted from the Americans and Chinese by the obstinacy of Syngman Rhee, though Logevall acknowledges that Mendes-France played his hand extremely well, at least until the treaty was signed.

The account of the transitional period does not place sufficient blame where blame is deserved—on John Foster Dulles. Dulles gratuitously insulted the Chinese, who had helped Mendes-France get a relatively favorable agreement, and thereafter encouraged the South Vietnamese to subvert the agreement by withholding the promised elections, as well as food shipments to the North. The American tendency to undervalue the French record overlooks the fact that the French war was conducted for a longer period, over a greater area, with fewer resources, and with a volunteer and polyglot army. The French war in the person of De Lattre de Tassigny had one outstanding general, and General Navarre’s tactic at Dienbienphu was not inevitably doomed to failure and indeed had more to recommend it than the four-year war of attrition against a more committed enemy later pursued by General Westmoreland.

Mr. Denby’s account of Charles De Gaulle’s career pays no attention to the general’s early book on the causes of Germany’s defeat in World War I, which proposed that “only the civil state, backed up by law, could defend freedom; for an army to run the State was the swiftest road to tyranny.” He also neglects the Frenchman’s penetrating critique of the American political system in the last volume of his memoirs, published in 1970 immediately before the judicial destruction of the federal system that De Gaulle so admired:

a federation of states, each of which, with its governor, its representatives, its judges, and its officials—all, elected—takes upon itself responsibility for a large part of the immediate business of politics, administration, justice, public order, economy, health, education etc. while the central government and Congress normally confine themselves to larger matters: foreign policy, civic rights and duties, defense, currency, overall taxes and tariffs. For these reasons the system [of separation of powers] has succeeded in functioning up to now in the north of the New World. But where would it lead France . . . a country the demands of whose unity coupled with the perpetual threats from outside have induced to centralize its administration to the utmost, thus making it ipso facto the target of every grievance . . . The inevitable result would be either the submission of the President to the deputies or else a pronunciamento.

Leave a Reply