Though the “opening” of the Russian archives is supposed to be a blessing for historians, there are plenty of reasons for skepticism. To begin with, “open” is an inaccurate term. What is available is selective, for so much remains closed, many papers are suppressed, others are inaccurate, and some are even doctored or otherwise falsified. What is worse, their contents are seldom properly evaluated or interpreted by historians. This volume is an example.

It comprises 79 letters written by Stalin to Molotov from 1925 to 1935 (including only three brief notes from 1936) and presented by the recipient to the Central Party Archive in 1969. In recent years, some of these letters were published in Russian periodicals. We cannot know why Molotov chose to donate these and not others, but it is plausible to conclude that he believed them to be “safe.” He was right: they are safe because they are unimportant, even insignificant. What about the years of the Stalin purges; of the crucial years 1939-1941 when Stalin chose to be a partner of Hitler’s Germany; or indeed of the entire period of the war and thereafter—the ten years when Molotov was the Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union? Letters from these times would be interesting, even though Molotov was only Stalin’s toady, an unimpressive bureaucrat, a wooden dolt (whom John Foster Dulles once called the most formidable of diplomats). It is the habit of strong men to rely on subservient people to administer their foreign policy. There are many examples of this, including Hitler’s Ribbentrop, and also that of some American Presidents, but I know of no one less independent and more subservient than Molotov.

The epistolary language is vulgar and marked, here and there, by communist terminology: a terminology that, in Stalin’s case, sometimes conceals rather than reveals. The very tone suggests what so few people have recognized and still do not: that the victory of the Bolsheviks reduced, rather than strengthened, the importance of Russia in the world; a giant muddy state isolating itself from the rest of the world, administered by people of cramped characters and cramped minds. Of course Stalin was an exception—sort of: a cunning peasant boss, instinctively good at intrigues, among a crowd of fourth-rate men.

There is one, perhaps telling, matter: that concerning Lenin’s so-called “Testament.” It is now obvious that the text of this was doctored, if not altogether falsified, by Trotsky, who gave it to the American communist Max Eastman. Consequently Eastman, who of course sympathized with Trotsky, published a version more complimentary to Trotsky than to Stalin. And when Stalin raised hell about this, Trotsky reacted in a cowardly and weak fashion. How many people in the West have loudly regretted for 60 years that the unspeakable Stalin, rather than Trotsky, should have been fated to bear the legacy of the great Lenin! Yet, if Trotsky or Zinoviev or Bukharin had governed Russia in the 1930’s, Hitler would have had little or no trouble in upsetting any of them, and finally in conquering the Soviet Union. Such is the irony of history.

The importance attributed to these letters by their American editors is vastly overstated. Stalin’s occasional remarks about “imperialists” were essentially the emanations of a suspicious isolationist who, while he did pay some attention to matters of world revolution and to the activities of communists abroad, treated them as definitely secondary elements in his considerations. Alas, commendable scholars such as Robert Conquest keep insisting that Stalin was a consummate Marxist. But this is utter nonsense, believed and stated by people who, from decades devoted to the study of the Soviet Union, have every reason to know better. It is not their factual knowledge but their understanding of human nature that is regrettably deficient. Yet Conquest’s praise for this volume seems modest when compared to that poured out in endorsements by Alan Bullock, Alexander Dallin, and others. Robert C. Tucker, in his otherwise reasonable foreword, asks: “Did Stalin dismiss world revolution in favor of building up the Soviet state (as Trotsky, for one, alleged at the time), or did he remain dedicated to world revolution?” Lih’s answer, based on the letters, is that in Stalin’s mind “the Soviet state and international revolution coalesced.” Coalesced? Perhaps. But which of the two really mattered to him? Stalin was crude, callous, cunning, and ignorant of much of the world; but he was no fool, and he eventually proved to be a great statesman, though no revolutionary. There is nothing in these letters to suggest the contrary.

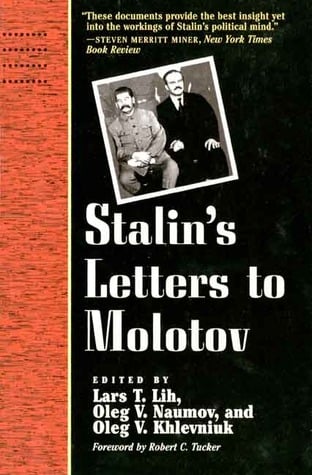

[Stalin’s Letters to Molotov 1925-1936, Translated by Katherine A. Fitzpatrick, Edited by Lars T. Lih and Oleg V. Naumov (New Haven: Yale University Press) 304 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply