Dr. Daniel Mahoney, the Augustine Chair in Distinguished Scholarship at Assumption College, has written a most scholarly and challenging book, in which he argues that “humanitarianism” without grounding in faith is a danger to our civilization. This philosophy seeks to create a “new man” and produce a “new humanity,” with roots in Auguste Comte’s “religion of humanity.” That “religion” has been described as “Catholicism without Christianity.”

Mahoney is especially concerned with “the perplexity that is Pope Francis,” and opines that the pontiff “is half-humanitarian and thoroughly blind to the multiple ways in which humanitarian secular religion subverts authentic Christianity.”

To develop his indictment, Mahoney calls upon a number of witnesses, including American Catholic convert Orestes Brownson, Hungarian philosopher Aurel Kolnai, Russian luminaries Vladimir Soloviev and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. Their commonality included their rejection of humanitarianism and their refusal to confuse peace with pacifism.

Pre-Catholic Brownson is described as “a ‘pantheist and a gnostic’ who believed that the Kingdom of God could be established on Earth.” Post-conversion, “Brownson foresaw all the evils associated with Communist totalitarianism in the twentieth century. He would have no sympathy for liberation theology or Christian Marxism,” writes Mahoney.

In his 2005 encyclical Deus Caritas Est, Pope Benedict advocates the principle of subsidiarity, the traditional Catholic antidote to the impersonal bureaucratic state that assumes the responsibilities of the people. Benedict rejects Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (as did his predecessor John Paul II), insisting that the Sermon on the Mount should not be confused with such coercive proposals in any way. Here Dr. Mahoney adds that “Christianity . . . has nothing to do with dogmatic egalitarianism. It sees poverty itself as an instrument of holiness.”

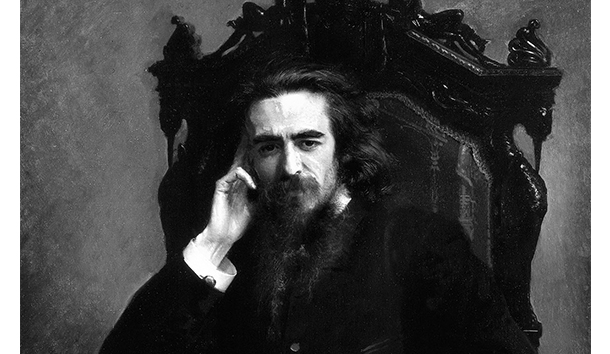

Vladimir Soloviev’s A Short Tale of the Antichrist is, according to Mahoney, “perhaps the most powerful and profound exploration of the humanitarian subversion of Christianity ever written.” Soloviev’s “appreciation of the power of evil” enables a critical rebuttal to “a moral optimism and historical progressivism that takes for granted the self-sufficiency of humankind.” Continues Mahoney, “his was a luminous Christian intelligence.” Soloviev is the counterpoint to his Russian contemporary, Leo Tolstoy, who insisted on “reducing Christianity to passivity, to the imperative of not resisting evil with violence and rejecting all wars.” Mahoney notes that “there is no place for the nation, or for patriotism” in Tolstoy’s humanitarian view of Christianity. Decades later, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn renewed the critique of Tolstoy’s pacifism.

“Evil must be resisted,” adds Mahoney, “and war paradoxically forms part of that resistance. . . . Evil is real, rooted in fallen human nature, and must be resisted if the things of the soul are to be preserved.”

Hungarian philosopher Aurel Kolnai is still more direct. Writing in 1944 of “the Humanitarian versus the Religious Attitude” (included in Mahoney’s Appendix), he contends that “humanitarianism gave rise to totalitarian secular religions, such as Communism and National Socialism, [regimes] that abhorred soft humanitarianism and aimed to build the ‘kingdom of heaven on earth.’” Kolnai, says Mahoney, declares that “the rejection of irreligious humanitarianism is the vital precondition for the recovery of an authentic humanism and of a Christianity that does not bow before the idols of modernity.” Against the totalitarian temptation, he upholds “the Christian notion of the person, [which] affirms human liberty and dignity while avoiding the illusion of thoroughgoing human ‘autonomy.’”

Turning to Pope Francis, Mahoney describes him as “a pontiff at the intersection of authentic Christianity and a misplaced contemporary humanitarianism” that nearly always identifies markets and capitalism with greed and environmental degradation. But “he is completely silent about the horrendous environmental devastation that accompanied and characterized totalitarian socialist systems in the twentieth century.” The author attributes the Pope’s outlook to his Argentinian roots, noting that “Peronist populism created a ‘rancid political culture’” there, one emphasizing “class struggle and redistribution.” Embracing this philosophy reduced Argentina from “the 14th richest country in the world in 1900 to the 63rd today.” Nonetheless, Francis seems to be more forgiving of “despotic regimes that speak in the name of the poor,” even when their leaders “viciously persecuted the Church.” One thinks of Fidel Castro.

The Pope’s misguided humanitarianism is also evident in his pronouncements on Islam, immigration, and abortion. In Mahoney’s view, Francis “errs when he states that ‘authentic Islam and the proper reading of the Koran are opposed to every form of violence.’” Mahoney notes that “Mohammed murdered many infidels, including the defenseless Jews of Medina,” and points to the tradition of “jihad of the sword.” On the matter of immigration, like some heads of state and exponents of humanitarianism, “Pope Francis rarely distinguishes between migrants . . . and genuine refugees fleeing war and religious and political persecution.” And like many Christian progressives, the pontiff is too often silent “about the grave and intrinsic evil of abortion,” and calls “for the global abolition of the death penalty.”

Toward the end of the book, Dr. Mahoney offers balance in his analysis of Pope Francis:

There is wisdom and insight to be found in the writings, speeches and addresses of Pope Francis. He is at his best when he thinks and writes in continuity with the full weight of Christian wisdom and with the insights of his immediate predecessors. But when he departs from them, he tends to confuse humanitarian concerns with properly Christian ones.

Distilling Mahoney’s analysis, John O’Sullivan writes that humanitarianism, in “its denial of evil, its hostility to human differences, and its elevation of comfort as the highest good,” is fated

to produce the opposite of what it promises: egalitarian tyranny, coercive bureaucracy in personal relations, the spread of euthanasia and abortion, the collapse of the future, and a growing listlessness in politics, culture, and religion.

I concur with Dr. Mahoney’s thesis, but wish that the case he offers could have first been filtered through the eminent pollster and political analyst Frank Luntz, the author of Words That Work. Luntz, through his surveys and legendary focus groups, demonstrates how some words are welcomed by those listening, while virtual synonyms can be negatively perceived. One example might be the “inheritance tax,” which has neutral or even positive connotations. Yet describing the same revenue stream as a “death tax” invokes not-so-friendly thoughts of “revenuers” arriving at a wake to gauge the government’s share of the decedent’s legacy.

Similarly, I wish there were a different way for Mahoney and the rest of us to consider “humanitarianism.” Ask 20 of your relatives and neighbors for their reaction to the word, and they are likely to nod in appreciative support. Who doesn’t admire humanitarians, after all?

Yet these same individuals would likely perceive “secular humanism” as a more controversial philosophy—embracing service to others, but to the exclusion of religious considerations and imperatives. “Loving real human beings,” writes Dr. Mahoney, “involves the exercise of the cardinal and theological virtues, which have little or no place in the new humanitarian dispensation.” Humanitarianism has reduced too many Christians reflexively to embrace “social justice,” says Mahoney, leading to the consideration of radical political ideas and a rigid egalitarianism.

[The Idol of Our Age: How the Religion of Humanity Subverts Christianity, by Daniel J. Mahoney, Foreword by Pierre Manent (New York: Encounter Books) 163 pp., $23.99]

Leave a Reply