by Frank Costigliola

Princeton University Press

648 pp., $39.95

How do you solve a problem like George Kennan? For a man who prided himself on intellectual rigor, he was, in practice, a bundle of contradictions.

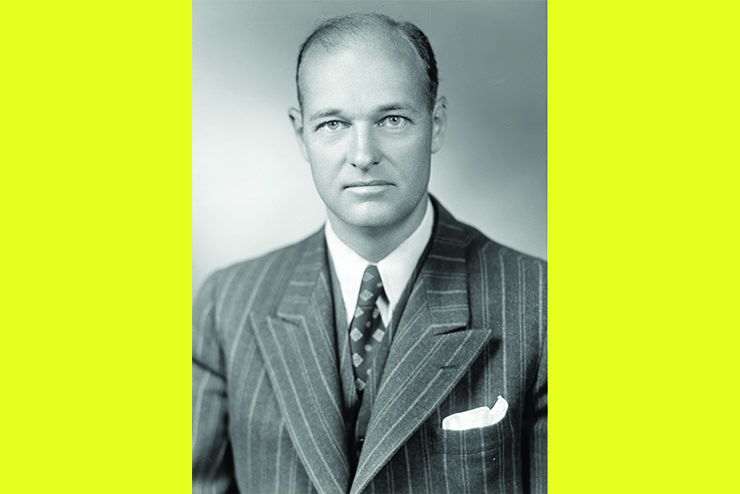

Kennan’s name is inextricably linked to American national strategy in the Cold War era, yet he never held an office higher than ambassador and never had direct policymaking authority. He was the author of the United States Cold War policy of “containment,” in which the U.S. would try to constrain the expansion of communism after World War II without confronting a nuclear Soviet Union directly. He first articulated his containment policy in the “Long Telegram” he wrote from Moscow in 1946 and a subsequent article on “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” he published in Foreign Affairs under the pseudonym “X.”

Ironically, Kennan spent most of his very long life trying to run away from the idea that made him famous, claiming that subsequent policymakers misunderstood his concept of containment by overemphasizing the military aspects of confrontation with the Soviet Union and missing chances for negotiation. He left government service in 1953 (returning briefly in 1961-63 as ambassador to Yugoslavia) and spent the next five decades as a gadfly against the establishment, from a sinecure at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Despite his criticisms of the Washington foreign policy establishment, Kennan found it impossible to embrace the critics of American foreign policy who wanted him on their side. In his private musings, this famous defender of American democracy against the Soviet threat was a lifelong Russophile who nurtured authoritarian dreams. A relentless critic of American materialism and consumerism, he sketched plans for supplanting raucous and unpredictable American democracy with government by experts like himself, insulated from the mindless enthusiasms that drove politics in the democratic American republic.

Even as Kennan derided his fellow citizens for their irrational lack of self-control, he was also a hypochondriac and compulsive philanderer. When he was not actively cheating on his long-suffering wife of 60-odd years, he imagined doing so and at the same time tormented himself with guilt, entrusting his fantasies and frustrations to a meticulously kept diary that covered nearly all of his 105-year life.

Despite or because of these contradictions, Kennan has long been a favorite subject for diplomatic historians, many of whom look to him as a model of the philosopher-policymaker they all wish they could be. In addition to his own award-winning memoirs and historical monographs, Kennan has been the subject of dozens of scholarly works, focusing either on him specifically or his relationship to the other “Wise Men” who shaped the foreign policy of the postwar American Empire.

Kennan’s longevity, however, proved something of a barrier to a complete picture of his life and thought, as he restricted access to much of his archive to the official biographer he had selected in the 1980s, John Lewis Gaddis, who agreed not to publish his study until after its subject’s demise. Gaddis’s monumental tome finally appeared in 2011 and garnered plaudits from near and far, including a Pulitzer Prize. It reflected the first concerted effort to relate the public Kennan to the diarist, though Gaddis’s respectful handling of the man he had known well for three decades may have resulted in some pulled punches.

Enter Frank Costigliola, a diplomatic historian of the same generation as Gaddis but from a different political and historiographical tradition. Where Gaddis has garnered fame as a “post-revisionist” scholar who generally defended containment, even in its post-Kennan form, Costigliola stands with revisionist critics of Cold War orthodoxy, inherited from his Cornell adviser Walter LaFeber and the broader Wisconsin tradition of William Appleman Williams, for whom American economic interests, not Communist rapacity, offer a better explanation for the Cold War.

Although not chosen as the official biographer, Costigliola was well suited to write a learned biography that acts as a counterpoint to Gaddis. Over the years, he had already devoted enormous attention to Kennan, including editing the published version of the Kennan diaries. Costigliola also has the second-mover advantage in that he was able to use the correspondence between Kennan and his official biographer to shape his narrative and even to frame the relationship between Kennan and Gaddis as part of the story of Kennan’s struggle to resolve his own contradictions.

Indeed, one could argue that the differences between Gaddis and Costigliola allow for a deeper understanding of Kennan’s contradictions. Early in his career, Gaddis published extensively on Kennan’s original ideas. He had less enthusiasm for Kennan’s later positions, however, such as Kennan’s calls for nuclear disarmament and American disengagement from Germany in his 1957 Reith Lectures for the BBC. Kennan saw those lectures, and his later criticisms of American military policy in Vietnam and the Reagan defense buildup of the 1980s, as vital to saving the world from catastrophe. Gaddis, however, had a hard time reconciling those views with his vision of Kennan as the architect of what Gaddis called the Cold War’s “Long Peace,” and so Gaddis generally dismissed them, as did most of the foreign policy establishment of the time.

Costigliola, however, centers his story on Kennan’s critiques of containment. He emphasizes how Kennan always saw the need to shift from immediate confrontation to negotiations with Moscow, drawing on his deep sympathy for the Russian people. He details Kennan’s eventual expulsion from the foreign policymaking world he so desperately wanted to influence. Costigliola also draws parallels to the present, as he notes Kennan’s rejection of arguments about expanding NATO and his preference for U.S.-Russian understanding over the interests of the smaller states of central and Eastern Europe. He paints Kennan accurately as a realist whose foreign policy vision centered on relations between Great Powers, who saw the system as a whole rather than being guided by one-sided conceptions of American national interest. For that reason, above all others, he praises Kennan for being “a man outside his time” and concludes: “His era desperately needed that perspective. So does ours.”

A general sympathy for Kennan as a man of “between worlds” provides the golden thread running through Costigliola’s long narrative. Devoting significant time to Kennan’s personal reflections and especially his formative years as a young diplomat in Berlin, Riga, and Russia, Costigliola highlights both Kennan’s fascination and sympathy for Russian language and culture and his skepticism about modern America. They were two sides of a coin for him.

Russian “backwardness” was for Kennan a feature, not a bug, as he imagined a world occupied by sturdy peasants and played the part himself on his Pennsylvania farmstead. For all his complexity, Kennan “never wavered in his love for nature, concern for the environment, discomfort with cities, and hatred for the hegemony of the machine.” This affection for Russia eventually dominated his thinking. The 95-year-old Kennan told a colleague that the Russians were “in many ways a great people” while “we are not, really, all that great.” He concluded that the United States was “the world’s spiritual and intellectual dunce.”

Even as he ends up praising Kennan the gadfly, Costigliola, like Gaddis, struggles with Kennan the man. As a Cold War revisionist in the classical mold, Costigliola clearly sympathizes with Kennan’s unorthodox views of the Cold War during the 1950s and 1960s. But he is clearly frustrated that Kennan did not have much time or patience for revisionist scholarship during his lifetime. Indeed, Costigliola devotes a fascinating section of the book to a seminar held at Princeton on the origins of the Cold War, in which Kennan sided with the orthodox Arthur Schlesinger against leading revisionists Walter LaFeber and Lloyd Gardner, showing “studied indifference” to their arguments. He also notes how Kennan undermined the scholarly work of many revisionist scholars, denouncing Gar Alperovitz’s Atomic Diplomacy, for example, as “so slippery and dishonest that its very publication is a disgrace.” Costigliola’s frustration boils over at one point when he says Kennan’s “sarcastic response” to some revisionists “was so petulant that it should have embarrassed him.”

Similarly, while Costigliola happily endorses Kennan’s critiques of the Cold War policies of John Foster Dulles and Ronald Reagan, not to mention his critique of NATO expansion in the 1990s, he is clearly disturbed by Kennan’s domestic political visions, especially his musings about rule by experts, skepticism about democracy, and disdain for an American society that was becoming less-dominated by WASP grandees like George Kennan.

Indeed, when one considers Kennan overall, with his anti-interventionist foreign policy, rejection of permanent alliances, discomfort with immigration, and contempt for popular culture, Kennan could best be described as a paleoconservative. Costigliola is certainly not a paleocon, and as a result his praise for Kennan is occasionally muted—even as he hastens to assure us all that he was “not a fascist.” Costigliola’s approach differs markedly not only from Gaddis but also from the recent short book by Lee Congdon, George Kennan For Our Time (reviewed on page 34) in which Congdon unabashedly endorses all of Kennan’s positions.

Costigliola is, however, too good a scholar to allow his personal views to cloud his judgment. His willingness to show all facets of Kennan’s character gives this biography lasting value for anyone who wants to understand the U.S. foreign policy establishment. Kennan would probably find fault with his conclusions, but then again, he generally found fault with everything except the wisdom of George Kennan.

Leave a Reply