“Farmer-poet” is one of those hyphenated epithets that summons up a vision, and for most readers of American poetry that vision is embodied by Robert Frost, who, the legend has it, turned out memorable poems in spare moments stolen from apple-picking, wall-mending, and woods-stopping. But Frost, despite his undeniable poetic stature, was never much more than a symbolic farmer, to borrow a phrase from his biographer, William Pritchard; his unsuccessful venture as a poultryman was mercifully cut short by an inheritance that allowed him to go to England, publish his first two books there, and return home in triumph to spend the larger portion of his days as a university poet-in-residence. As great as Frost’s poems about farming are (and the list is long), one gets the impression that the literal drama of farm life interested him less than its inexhaustible stores of metaphor by which he might extend and universalize the farmer’s experiences.

With Frost, the hyphen between farmer and poet should be an arrow pointing toward the latter, and his case is typical: How you gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen the Paris Review? Farming brings with it such potential for heartbreak that it strikes me as odd that, while novelists like Gather and Steinbeck have explored its capacity for tragedy, only rarely in our poetry have the four horsemen of drought, disease, flood, and freeze made an appearance. Henry Mahan, a talented poet I knew in graduate school who never, to my knowledge, published a collection of verse, once wrote a poem titled “The Chicken Farmer’s Vision of Doom”:

Dead chickens ain’t no good to eat.

No chickens hatch from rotten eggs.

My shoes are rotting off my feet.

My feet are rotting off my legs.

Years ago I thought that witty, surreal, and preposterous, but as I drove from Beaumont to Austin recently during our unrelenting Texas drought and saw field after field of parched, withered corn, Mahan’s quatrain came back to me with utter seriousness. Every blasted acre represents yet another farmer’s dream deferred, if not killed outright. How many prayers, in this year of El Niño, have been offered for what nature can so abundantly provide or withhold? And what poet has given voice to those prayers?

Wendell Berry has. The poems in A Timbered Choir originated as “Sabbath poems,” meditations written over two decades. Sunday walks provide the occasions, and the appropriate themes of hard-earned rest and hopes of renewal surface on virtually every page. At times, Berry describes a stewardship of the earth that is rewarded with only an overwhelming sense of fatigue. In one poem he reminds us that “As grist is ground to meal / The grinders are ground down”; in another,

I climb up through the field

That my long labor has kept clear.

Projects, plans unfulfilled

Waylay and snatch at me like

briars.For there is no rest here

Where ceaseless effort seems to

be required.Yet fails, and spirit tires

With flesh, because failure

And weariness are sure

In all that mortal wishing has

inspired.

If it were always thus, one might protest that the woods are indeed too “lovely, dark and deep” to resist and that the farmer-poet—”promises to keep” be damned—is justified in burrowing into a snowbank. But Berry, while he never lets us forget the weight of his quotidian chores, is equally a poet of praise. His mood is most elevated by signs of seasonal advent. In one poem he stands beside “a ragged half-dead wild plum / in bloom, its perfume / a moment enclosing me.” Even if the old tree, like the rest of us for that matter, has few long-term prospects, it still causes the poet to “recognize as a friend / the great impertinence of beauty / that comes even to the dying.”

Berry’s reputation as a social thinker so far precedes him that it is at times difficult to separate the poet from the polemicist. While many of the poems display sure craft (the larger portion of them are metrical and rhymed) and coherent content, one is left with the impression of having read a lot of poetry but only a few poems. At Berry’s weakest moments, his language is flat (“Where ceaseless effort seems to be required”) and his lines are indistinguishable from prose:

It is the destruction of the world

in our lives that drives us

half insane, and more than half

To destroy that which we were given

in trust: how will we bear it?

But at his best, in a wonderfully direct 13-page poem called “The Farm,” he underscores what every farmer knows but few have articulated: of all those who labor for the sake of permanence, the farmer stands most tenuously on the land he works. The earth always stands ready to cover over the faint marks of a lifetime’s toil. As Berry puts it,

And so you make the farm

That must be daily made

And yearly made, or it

Will not exist.

Those who are most attracted to A Timbered Choir

Timothy Murphy may, like Berry, have a trusty ax to grind, but he is determined to sharpen it deliberately, with each stroke of the whetstone corresponding to an individual line, stanza, or poem—a care that is attested to by his waiting until his fifth decade to publish a full-length collection. Murphy studied with Robert Penn Warren, and he seems to have taken to heart the Old Agrarian’s lessons about the virtues of memorization: the poems, which are for the most part brief, tightly formal, and ironic, cry out for recitation. “Twice Cursed” opens the book:

Bristling with fallen trees

and choked with broken ice

the river threatens the house.

I’ll wind up planting rice

if the spring rains don’t cease.

What ancestral curse

prompts me to farm and worse,

convert my woes to verse?

Richard Wilbur’s generous introduction characterizes Murphy’s most typical voice as that of “a Dakota farmer who knows everything about outrageous extremes of weather, crop failure, and the many adversities which can lead to falling-down barns and ghost towns.” But this lugubrious list of catastrophes does not necessarily result in songs in the key of Dirge. Wilbur says, rightly I think, that in converting “woes to verse” Murphy emerges with “the jauntiness of a survivor, and the high morale of a man who has a purchase on reality, however bleak.”

Murphy strikes me as a remarkably original poet, one whose unique sound and vision fly in the face of so much conventional wisdom about what present day American poetry is supposed to be. To be sure, his subjects are resolutely contemporary; along with the poems about farming are others exploring subjects as diverse as sailing, homoeroticism, hunting, other poets (Wilbur and A.D. Hope are the recipients of two thoughtful homages), art, purebred Labrador pups (in Scots dialect!), and Li Po. Still, Murphy’s poetry goes so against the grain of what is usually praised (and overpraised) in contemporary practice that one is almost forced to re-educate himself to appreciate the triumphs here. His short meters force the reader to hear the rhymes in a way that many contemporary formalists go out of their way to avoid; he gives us a poetry that looks back, with no regrets for the legacies of Modernism, to Hardy and Housman in both technique and philosophy. The latter, who appreciated equally the classics and lightfoot lads, must somewhere be smiling in approval at “Memo to Theognis”:

No man is happy

unless he loves smooth-hooved horses,

hunting dogs and boys.

Happy with boys,

horses and dogs?

No man enjoys

a boy’s esteem for long.

Horses go to the dogs,

and dogs die young.

I do not know how many contemporary readers, whose palates have seemingly been conditioned to prefer an unmellowed whine to vintage wine, will fully savor the delights of this auspicious debut, but I, for one, hope that this poet will get the hearing he deserves.

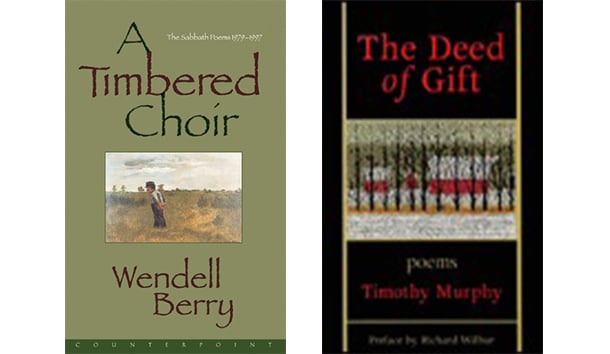

[A Timbered Choir: The Sabbath Poems, 1979-1997, by Wendell Berry (Washington: Counterpoint) 216 pp., $22.00]

[The Deed of Gift by Timothy Murphy (Ashland, Oregon: Story Line Press) no pp., $12.95]

Leave a Reply