“In literature, it is the hereditary spirit that still prevails.”

—George Santayana

Nothing is more dangerous for the critic than taking a book cover at face value. But when the blurbs compare the author to William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, and Saul Bellow, the challenge is irresistible. And since these are the claims with which Harper & Row confronts the reader of Robert Towers’ novel, The Summoning, the publisher is setting its own standards for the critics. Remarkably, the novel does not disappoint unless it is held up to those high literary comparisons the publisher has implanted in the reader’s mind.

Although the action is set in the South and Towers tries to evoke a heavily Southern atmosphere, the comparisons to Bellow and to a lesser extent Percy, with their depictions of existential angst and quests for “meaning,” are more valid than the evocations of Faulkner and O’Connor. More important, the novel raises questions which have disturbed sensitive critics over the past decade or so; Why does even the best-written, most ambitious, and well-crafted of contemporary literature seem “minor”? Why has no literary voice emerged to capture indelibly whatever soul is left in contemporary Western culture? And what are the implications of this failure— whether of the imagination or of the culture it would reflect—for us, the audiences the art must speak to? With the exception of the 81-year-old Robert Penn Warren, no major writer in America today bears comparison with the remarkable generation of writers who dominated our literature after World War I—which was precisely when Warren got his precocious start as the youngest member of the Fugitive group of poets.

An insightful explanation for the contemporary crisis in American letters comes from a retrospective essay, “Why the Modern South Has a Great Literature,” by Donald Davidson, one of Robert Penn Warren’s Fugitive colleagues and teachers. According to Davidson, great literary epochs occur when artists are forced into “a moment of self-consciousness” because their traditions are threatened by certain cultural and social changes, “when a writer awakes to realize what he and his people truly are, in comparison with what they are being urged to become.” He defines a traditional society as:

. . . stable, religious, more rural than urban, and politically conservative. Family, blood-kinship, clanship, folkways, custom, community, in such a society, provide the needs that in a non-traditional society are supplied at great costs by . . . governmental agencies. A traditional society can absorb modern improvements up to a certain point without losing its character. If modernism enters to the point where the society is thrown a little out of balance but not yet completely off balance, the moment of self-consciousness arrives.

Davidson supports his thesis with Periclean Athens, Rome of the late republic, Dante’s Italy, and Elizabethan England. His argument can aid greatly in placing a novel like The Summoning in perspective.

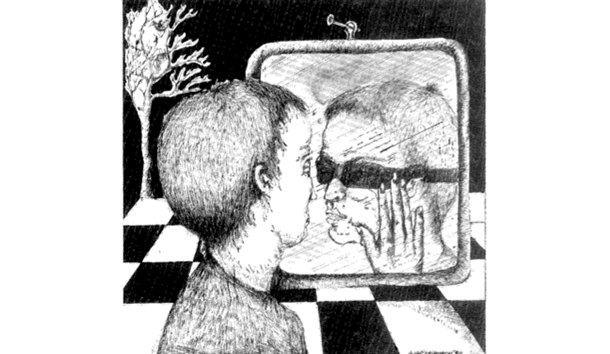

It is almost axiomatic now that the self-consciousness of our culture has become a kind of narcissism; as Tate put it in one of his best poems, contemporary man has become like some bloated Alice, paralyzed by her own image in the looking glass and stripped of volition to act. This extension of the modern dilemma from protest to self-indulgent subjectivism is inevitably reflected in the art. The voices of World War II are the likes of Norman Mailer and James Jones; of the Korean War, only William Styron; and while there is a growing body of interesting Vietnam-like period fiction, no definitive voices have emerged to bring meaning to the chaos. The traumas of the Holocaust and the Civil Rights and feminist movements have produced painful cries of ethnic and sexual outrage, but no great art. Earlier Depression-era fiction, with its proletarian focus, already seems badly dated. Such is the context in which the highly touted Towers novel must be read.

Towers, a Southerner who earned his Ph.D. at Princeton and now teaches at Queens College in New York, develops his story of revenge and spiritual revelation in the dramatically potent setting of post-civil-rights Mississippi. The protagonist, Lawrence Hux, is also a transplanted Southerner, Princeton Ph.D., and a foundation executive in New York. In his late 30’s, Hux is divorced and approaching a mid-life identity crisis involving his past as well as present life. While working as a civil-rights activist in Mississippi during the early 1960’s, Hux had abandoned his mission to return to Princeton. Carrying on the struggle, his best friend is eventually murdered by a prominent small-town doctor who, in the volatile atmosphere of those days, was acquitted in a local court. Now—10 years later—a haunting apparition of the martyred friend stirs up Hux’s guilt and sends him back to Mississippi to exact his personal revenge. What he finds there, in the waning days of the Watergate crisis, is the crux of the novel.

Inventing as a pretext for his return a foundation project to study library collections at several Mississippi colleges, Hux is drawn into an elaborate masquerade which allows him to insinuate himself into Dr. Claiborne Heme’s life. He discovers the doctor to have become a shattered recluse, living alone with his spinster sister and the ghosts of his own guilt. Before the murder, Dr. Heme had been a patrician patron to local black youths. One of his protégés, ironically named Rooney Lee, now dominates the doctor’s life by forcing him to submit to flagellation by Rooney’s wife. Hux takes advantage of a religious vulnerability in Heme’s sister to pose as an evangelist and win her confidence, but then, while attending a real evangelical tent-meeting revival, undergoes a profound religious conversion himself and is forced to reexamine the implications of his vengeance. In the zeal of his new faith, Hux confronts the doctor with his crime and forces him to kneel in prayer. The novel ends tumultuously with Dr. Heme’s suicide and Hux’s near-fatal beating by the criminal Rooney Lee.

Perhaps the publishers and early reviewers should be forgiven for drawing obvious parallels between The Summoning and the works of such authors as Bellow, Percy, O’Connor, and Faulkner. The emptiness of Hux’s New York life and career—divorced, deprived of his son, and void of professional satisfaction—is the familiar existential problem of much modern literature. When Hux is “summoned” to avenge his dead friend’s murder, his life assumes purpose, although it is the discovery of his true summons that exorcises the ghosts of the past and frees the emotionally crippled Hux to love again. The Deep South setting and the treatment of racial guilts are, of course, highly suggestive in themselves. Many readers will recognize characteristics of “Southern Gothic” literature. There are unmistakable echoes of such religious grotesques from Flannery O’Connor as the fake Bible salesman Manley Pointer in Hux’s imposture as a traveling evangelist, of the “Misfit” in the malevolent Rooney Lee, and of Hazel Motes, whose mission to found a “Church Without Christ” becomes a profound spiritual quest. But The Summoning ends on an ambiguous theological note, as Hux (who has at least been reborn to the capacity for commitment) says, “Jesus was the name I spoke, the name I prayed to. But the name doesn’t seem necessary to me now, maybe not even useful anymore.” The apparent parallels with O’Connor, Percy, or Faulkner prove misleading. Towers does not show Percy’s talent for exposing the absurdities of contemporary life in comic action. And he lacks O’Connor’s ability to kick the reader in his literary stomach; the novel is devoid of the metaphysical hilarity that makes us laugh at her characters while we are aghast at their fate. Nor does Towers—or any other writer today—possess Faulkner’s Olympian vision of the myth and tragedy implicit in the Southern experience.

Still, no less a writer than Eudora Welty has complained of the problem of settling down to write her “delta” fiction only to be haunted by the shadow of Faulkner’s mountains looming on the horizon. Ernest Hemingway used to describe writing as a kind of boxing competition, of putting on the gloves with the likes of Turgenev or Stendhal, and Towers undoubtedly knew what he was taking on in The Summoning. In fact, the ghost of Southern fiction past—especially the example of Faulkner—is one of the spirits the novel explicitly attempts to exorcise, even as the author inevitably evokes it.

Jean-Paul Sartre once compared Faulkner’s vision of the world to “that of a man sitting in a convertible looking back.” Only the past is real. At one point early during his visit to Ole Miss, Hux—in his role as foundation executive—uses one of the “Faulkner Weekends” held regularly there to revere and exploit the author’s name as an occasion to ridicule the Southern tendency to dwell on what is lost. Seated next to a visiting Faulkner scholar, Hux adopts an exaggerated Mississippi accent to taunt the professor’s infatuation:

I’ve just been proposing . . . that sump’m ought to be done about Bill Faulkner’s body . . . that they ought to exhume it, and then hire a team of expert morticians to touch it up so’s they could exhibit it. You know, jus’ like Lenin’s, only in the parlor at Rowan Oak ‘stead of the Kremlin.

By mocking the adulation of Faulkner, Towers is trying to escape from the shadows still cast by the giants of the Southern Renaissance. Yet it is Hux’s own idolatrous worship of his dead friend’s memory and his own sense of lingering guilt from the past that has provoked his own quest for revenge and redemption.

But the past does not mean for Towers what it meant for Faulkner, for in the end Hux does leave his past behind, convinced that his murdered friend won’t “come back that way again.” And in spite of the author’s effort to avoid the stereotypical “Southern” novel, the familiar figures and themes are all here, if sometimes developed with a new twist. The fundamentalist evangelist who converts Hux to his own firebrand religion by recounting his own sins and then offering the possibility of rebirth—”I that was dead am now living”—is never revealed satisfactorily as either charlatan showman or divine instrument. The depiction of the maverick Rooney Lee, though, suggests that Towers is developing a more complex approach to the “Southern problem” of racial guilt, one rising above the simplistic hair-shirt of racial guilt. But the customary small-town Southern characters abound—especially Dr. Hcrne and his spinster sister. And the city (Memphis, in this case) is painted in the usual colors of sinister corruption.

The occasional lapses into caricature and stereotype do not, however, obscure the author’s genuine talent. In its virtues and its faults. The Summoning might put the reader most in mind of Robert Penn Warren, as novelist. Like Warren, Towers is an expatriated Southerner. Over his last five or six novels, Warren—transplanted to Yale and Connecticut—has shown a progressively less-sensitive “feel” for the pulse and soul of his regional material, and his Southern voice seems increasingly strained. Towers is struggling with the same problem. The Summoning is marked by a great deal of documentary realism—descriptions and references to Memphis and northern Mississippi will be familiar to any reader who knows the lay of the land—but the familiarity is uneasy, and the novel lacks that un-self-conscious use of natural resources that the reader is more affected by than aware of But like Warren, Towers is willing to take on large themes with intelligence and skill, no mean feat in today’s literary climate.

[The Summoning by Robert Towers, New York: Harper & Row]

Leave a Reply