On July 25, 1997, Ben Hogan died in Fort Worth at the age of 85; his widow, Valerie, did not long survive him. In the season of 2000, Tiger Woods smashed scoring records in the U.S. Open, the British Open, and the PGA Championship, winning nine tournaments for the year, and setting the golfing world on its ear. So what happened? Book after book on Hogan emerges, as though the man hadn’t won his last tournament at Colonial in 1959, and as though he had not since departed the scene in more than one way. The evidence says that Hogan never left us, and that Hogan, not Woods, is the man people think of when they consider that infernal anomaly, the golf swing, and the challenge of golf itself People still talk about Hogan—they do so even when they talk about Woods. Tiger’s nine wins were a lot, but Hogan won 11 in 1948 and 13 in 1946. Tiger Woods won three out of four major championships in 2000, but Hogan won three out of the three he entered in 1953. At the Players Championship in 2000, Hal Sutton explicitly refused to be intimidated by Tiger Woods, and a look in his bag revealed one reason why: a set of irons forged with the name Ben Hogan. The man just won’t go away.

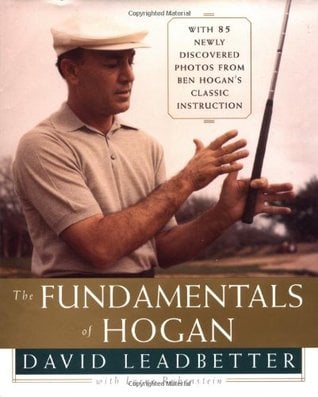

In recent times, we have seen the release of various videotapes devoted to Hogan, such as Clem Darracott’s In Pursuit of Perfection (The Bootlegger, 1995), an excellent home movie of Hogan practicing at Augusta in 1967; a digitized version of Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf, Hogan vs. Snead at the Houston Country Club, as aired February 21, 1965 (also Bootlegger); and the Golf Channel’s Ben Hogan: The Golf Swing, in which Jim McLean does verbally much of what Leadbetter has done in text. And there have been books. A short list would include Curt Sampson’s hostile and unauthorized biography Hogan (1996), which is largely devoted to analysis of a remote personality. Mike Towle’s I Remember Ben Hogan (2000) is a miscellany of reminiscences assembled as though to refute Sampson (Hogan liked children and dogs). John Andrisani’s The Hogan Way (2000) is a shrewd and useful study of Hogan’s theories as opposed to his practice, and that brings us to the present volume, with which it has much in common. David Leadbetter, the number-one golf teacher in the world, has worked with some of the best players, perhaps most notably Nick Faldo and Nick Price. Like Andrisani, Leadbetter has framed his book around Hogan’s famous one; like Andrisani’s, but more so, it is enriched by a wealth of revealing photographs.

Hogan’s second book, Five Lessons: The Modem Fundamentals of Golf (1957), has never been out of print and has sold over six million copies. Although it is the most important work ever written on the golf swing, those who have studied it have noticed that it has certain limitations. Hogan’s vision of the swing as expressed in that study is both instructive and exemplary, as well as idiosyncratic to the point of eccentricity. Andrisani and Leadbetter have insisted that there is a significant gap between what Hogan said and what he actually did. There is another one between the Hogan vision and the instructional paradigms of contemporary teaching professionals such as McLean, Andrisani, and Leadbetter.

In Leadbetter’s case, the result is both instructive and yet amusing, though in a way that begins to sour. Leadbetter’s revisions of Hogan become rather predictable. On the hands, for example: Hogan advocated a “weak” grip, but Leadbetter doesn’t. Hogan wanted a “short” left thumb, and Leadbetter wants a long one. Hogan wanted the club in the palm of the left hand, but Leadbetter doesn’t. Hogan cupped his left wrist at the top of his backswing, but Leadbetter doesn’t recommend it, even though Hogan once declared that this position was his “Secret.” Instead, Leadbetter mentions cupping the other wrist. Hogan supinated the left wrist at impact, and Leadbetter likes that, as well he should. What is the alternative? On the address position: Hogan wanted the right foot square, whereas Leadbetter wants a freer approach, with the foot tipped out—a concession to humanity, like many of his revisions. Hogan advocated a wide stance, Leadbetter a narrower one—and for good reason, though Andrisani goes the other way on this point, as does McLean. Leadbetter equivocates on whether Hogan had a reverse pivot, and advocates loading the right side in contradistinction.

On the downswing: Leadbetter insists that Hogan did not do what his book says he did: begin the weight-shift by turning the hips. There was a hip-slide first, as we can see in photographs and film and videotape, and McLean and Andrisani have confirmed this point. Leadbetter goes so far as to recommend “exactly what Hogan advised against”—a pronated left wrist at impact for certain “closed-to-open” players. But even before this, the reader must have already sensed a quality of absurdity—the paradigmatic swing, constantly mentioned and analyzed and illustrated, is repeatedly qualified and even reversed, as Leadbetter works his image of the swing further and further from the Hogan model. And human physiognomy and variety being what it is, Leadbetter has his reasons, as usual.

We are left with an excellent book of instruction, sumptuously illustrated with images any Hoganite must have. But we are also left with a text that Sigmund Freud and, even more, Harold Bloom, would find revealing. Leadbetter had a commercial motive for framing his arguments around Hogan, no doubt. But as an anxious revisionist, he is in the position of a Romantic English poet trying to work around Milton. The belated visionary squirms as he tries to escape from the anxiety of influence and the primal example. Finally, to swing like Hogan, you have to be Hogan, and not even Faldo or Price or Woods can do that. To instruct like Hogan, Leadbetter has deconstructed the towering example, with ambiguous results. At the end, golf is still a mystery, exegesis is contingent, and all the hackers mumble “Hogan” as they swing away, more with hope in things unseen than any faith in repeating variable results.

[The Fundamentals of Hogan, by David Leadbetter, with Lorne Rubinstein (New York: Doubleday and Sleeping Bear Press) 133 pp., $27.50]

Leave a Reply