What is it about Ayn Rand that so fascinates her enemies as well as her admirers? Her two major novels, Atlas Shrugged (1957) and The Fountainhead (1943), are enduring pillars of popular culture. Her paeans to egoism make Nietzsche look like a piker, and, quite unlike that sickly aesthete, she had a life as dramatic and eventful as a Wagnerian opera, and there was about her the air of a Valkyrie. Some 15 years after her death. Rand has become the object of renewed attention. While the critics have always hated Rand and academia shunned her, ordinary people who do not know what is good for them buy over half a million copies of her books each year. Anything with her name on it is money in the bank for publishers, authors, and hawkers of Rand memorabilia, and lately the market has been going up. It was inevitable that Hollywood would get in on the action, and two Rand films have already been made, including a Showtime movie entitled The Passion of Ayn Rand, scheduled for release before this issue of Chronicles hits the stands. The movie is based on the part-hagiographic, part-hateful, and entirely self-serving memoir of her ex-disciple, Barbara Branden, who recently turned a cool million-plus by auctioning off her collection of Rand memorabilia. In true Randian fashion, her ex-husband, Nathaniel Branden, once Rand’s chief disciple, has engaged in none-too-friendly competition with Barbara to see who can profit more from the rise in Rand’s stock. So far, he seems to be losing out: His own memoir, Judgement Day—a sour grapes kiss-and-tell potboiler that focuses not on Rand but on his own bombastic self—followed Barbara’s book and did not do as well. But like one of Ayn Rand’s heroic entrepreneurs, who delight in cutthroat competition, Mr. Branden has not given up: His book is being reworked and reissued under a more salable title: My Years With Ayn Rand.

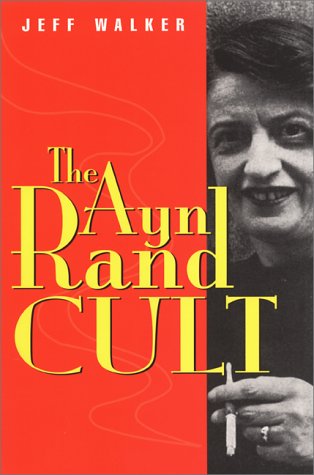

Ayn Rand herself, it is safe to say, would have been appalled by nearly everything produced by the Brandens. One may infer, moreover, how she would have evaluated the stilted, derivative, and unconvincing writings of her latter-day followers, which lack the essential ingredient she infused into all her writings—passion—while undergirding a movement that has inherited all of her crankier, more tiresome, and least interesting eccentricities: her fanaticism, her didacticism, and her obsessive hatred of Immanuel Kant, a philosopher whose works she never bothered to read. This movement is the focus of Jeff Walker’s The Ayn Rand Cult, the latest book—and, perhaps, one of the strangest—in the ever-expanding field of “Ayn Rand studies.”

Here is a tome of some 300 pages, seemingly devoted to proving that Rand was a psychopath who delighted in dominating and then destroying her followers, and whose megalomaniacal rages were fueled by amphetamines and a fullblown delusional system of almost demonic power. Walker’s story relates how Rand, after the publication of The Fountainhead, gathered a circle of much younger acolytes around her, and how this group expanded and soon took on all the characteristics of the classic cult; worship of the leader, blind dogmatism, psychological abuse, indoctrination and mind-control in the guise of “therapy,” and periodic purges on the model of the Moscow Trials. What he fails to tell us is why we should care —or why, for that matter, he cares.

In his preface. Walker suggests that reading The Ayn Rand Cult as an attempt to refute Rand would be “missing the point”: His main concern is not her ideas but rather the cultist nature of the movement she created. While the author develops a valid thesis, his focus on the organizational and personal dynamics of the movement excludes nearly everything else: There is almost no discussion of Randian ideology, and precious little mention of the source of the whole movement and its attendant organizations, theoreticians, and internecine squabbles—Rand’s novels. Walker assumes that the reader already knows the plots of her novels and is familiar with the principal characters, as well as the ideology, that animates them. Without a chapter summarizing the ideological and emotional context in which the events described took place, the cumulative effect of Walker’s catalogue of purges, excommunications, and betrayals is to raise the inevitable question: So what? He quotes one of Rand’s excommunicated acolytes as bitterly exclaiming that her experience in the cult was “‘a major traumatic life experience, its splendors attached to ‘a lot of agony.'” But what about those splendors? Of this there is nothing, and so the great appeal of the Rand cult remains mysterious. Walker notes that “nearly always, new converts to Objectivism are young,” but fails even to speculate on why this is so.

Although seriously flawed, The Ayn Rand Cult does provide a useful service in debunking Rand’s claim to have invented reason, individualism, and the concept of natural rights. While this claim may be absurd on its face, the old saw that any doctrine (no matter how deluded) can find at least some adherents applies to the libertarian movement in spades. The libertarian myth that, before Rand, there was only Darkness and Old Night is as false as the conservative myth that, before the founding of National Review, the American right did not exist, save in some barely recognizable form. Walker also performs a public service in exposing Nathaniel Branden as a con man and a cad who not only exploited Rand financially, emotionally, and in every other way, but had the gall to write a most unpleasant book about it.

In Walker’s book, Rand holds her followers in thrall by the sheer force of her personality and her indomitable will. Yet they would never have fallen under her spell in the first place had not the sheer narrative power of her novels made them susceptible to it. Like Rand’s contemporary followers—and like Rand herself after the publication of Atlas Shrugged—Walker loses sight of the artist and sees only the founder of a sect. He cavalierly dismisses her fiction as thinly disguised capitalist agitprop, and yet The Fountainhead—the story of a principled architect who refuses to compromise his ideals—dramatizes the essence of authentic individualism without any explicit reference to politics. While the literati were churning out slender novels about sensitive young souls in search of the ineffable, Rand had a vision of a sturdier and far healthier aesthetic. She also had a great satiric sense, a talent for drawing a devastating portrait with just a few well-placed brushstrokes; the young and adventurous were natural- Iv drawn to her iconoclasm. And so the smoke from Walker’s scorched earth approach to his subject obscures the really interesting question about the Rand cult: How could a movement ostensibly devoted to individualism become so mired in groupthink and dogmatism?

[The Ayn Rand Cult, by Jeff Walker (La Salle, IL: Open Court Publishing) 396 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply