At the end of the first volume of Charles Moore’s lapidary trilogy, we left Mrs. Thatcher standing in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1982, surrounded by the shades of past national leaders, bathed in public approval and growing global respect as the victor of the Falklands War and standard-bearer for a new and dynamic kind of conservative politics. This keenly anticipated second installment carries on her career from that triumph down to her final electoral victory in 1987. It was during this lustrum that her political style started to become apparent and her legacy began to crystallize, as she dealt, often successfully, with systemic problems lesser leaders would never have attempted.

From Hong Kong to Washington, Brussels to Jerusalem, privatization to perestroika, seething northern miners to South African sanctions, whether addressing both houses of the U.S. Congress or crawling shoeless away from her bombed Brighton bedroom, Mrs. Thatcher not only clung to power but became ever more armor-plated. By the time she won her historic third term, she had become, for an adoring social segment of the country, the personification of Britannic pluck, so apparently immoveable that her party was often seen (and saw itself) as “the natural party of government.” For a smaller but more voluble social segment, she was the loathsome “Leaderene,” the personification of all that was authoritarian, heartless, and philistine. Moore shows expertly with what combination of skill, verve, and good and bad luck this came to pass—also what opportunities Mrs. Thatcher and her regime overlooked, which issues they mishandled, and what stresses were building below the surface of her government.

As if the Falklands were not enough to deal with in the course of a year, 1982 also saw plans to privatize British Telecom and revolutionize welfare and education, negotiations with Beijing about the hand over of Hong Kong, visits to the newly elected Helmut Kohl, the death of Leonid Brezhnev, and the election of Garret Fitzgerald as Irish Taoiseach. Mrs. Thatcher brought energy and originality to bear on all these disparate matters, frequently against the will of officials and even her own ministers, as she zeroed in remorselessly on details, often at the expense of the bigger picture, impervious to boredom, sometimes wearing others down, sometimes being worn down herself by institutional inanition.

Her record is more mixed than either her emphatic personality or later mythologizing would suggest. She is justly celebrated for her role in American-Soviet relations, drawing Gorbachev into play, steering delicately between reassuring a jittery Soviet Union and lecturing its new leader, diplomatically papering over disagreements between the U.K. and the U.S. over Grenada and SDI, and restraining Reagan’s occasional naiveté. (“It is inconceivable that the Soviets would turn over their last nuclear weapon. They would cheat. I would cheat.”) It was characteristic of her that when she was offered a rare, behind-the-scenes tour of the Kremlin, she replied, “Do you think I’ve come here as a tourist?”

Other foreign policies were holding actions, such as in the Middle East where she qualified strong support for Israel with distaste for the Likudniks and arranged vast arms deals with the Saudis. Hong Kong was always going to be a defeat, but she played an impossible hand well. One of the more obscure stories herein is her policy on South Africa, which earned her vast opprobrium and embarrassed her ministers. She disliked apartheid as incompatible with liberty, and never felt comfortable with Afrikanerdom. She was also the first British prime minister to request the release of Nelson Mandela. But she also shared “personal sympathies” with the white population, which included some of her husband’s relations. She thought sanctions would harm blacks more than whites, and believed besides that Britain had an absolute right to her own trade and foreign policy—views widespread among the British public. She hated the moral grandstanding of countries like France and Canada, which called for sanctions in public but traded in secret—and of the Commonwealth, some of whose states were more dictatorial than the RSA. South Africa was furthermore a strategically important anticommunist power. Yet she yielded, probably because of pressure from the Queen—“probably,” because the weekly discussions between sovereign and prime minister are private, and Mrs. Thatcher would never breach punctilio.

Argument still sputters about her Irish legacy. Instinctively Unionist, she nevertheless brokered the Anglo-Irish Agreement in conjunction with Garret Fitzgerald, whom she found infinitely more congenial than Charles Haughey, if garrulous. (On one occasion she fell asleep during one of his expositions—“Keep talking,” her private secretary Charles Powell encouraged the Taoiseach, “I’ll write it all down.”) The reasons were manifold. As was so often the case on other matters, she was alone in her Unionism, the chief British negotiators having Irish sympathies to the extent that, as Moore notes, “Ultimately, it was not a negotiation . . . ‘How do you persuade the Prime Minister?’ was the question.” The Unionist political leaders were unhelpful. She saw the Ulster Unionist Party’s James Molyneux as “not a strong person,” while Ian Paisley was “not easy” (a masterly understatement). Enoch Powell, an Ulster Unionist MP as well as a small-c conservative mage, might have toughened her resolve had he been more astute, but Powell alienated her forever by accusing her of “treachery.” It was unsurprising that Unionists were effectively excluded from the talks, which disquieted even Green-leaning Foreign Office negotiators. The only aspect of her Irish involvement that all (perhaps even the IRA) admired was her selfless serenity in the aftermath of the 1984 bombing of the Grand Hotel in Brighton, when she left her damaged room to check on the secretaries across the corridor, coolly went back in to pick up her clothes, and was pleased to be handed the text of the next day’s speech as she was being bundled away by police. “The conference will go on as usual,” she told the BBC in the small hours, and English hearts swelled with proprietorial pride. Even this explosive irruption did not alter the pro-Dublin tenor of the talks. Moore still sounds surprised that there had been “no attempt to take political advantage.”

But it is regarding Europe that her ghost is most often invoked, Thatcher being seen then—and now—as archskeptic, securer of rebates, slasher of red tape, handbagger of Eurocrats, and voice of England. When she was shown a picture of Mitterand and Kohl holding hands in a reconciliatory way at a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of Verdun, and was asked whether it wasn’t moving, she replied “No, it was not—two grown men holding hands!” But fond folk memories of brusquerie and intransigence occlude the untidy actuality. Although she secured a swingeing 66-percent rebate in the British contribution to the E.U. at the stormy summit at Fontainebleau in 1984, the concession must be seen in the full light of U.K.-E.U. relations.

The Foreign Office customarily viewed negotiations with the rest of the E.U. in specific, detailed terms, focusing on economic gains and ignoring anything that seemed “merely” theoretical. Mrs. Thatcher likewise had a “congenital anxiety to understand the detail of everything,” and so, like a career diplomat, she failed to see the forest for the strangling undergrowth. But E.U. negotiators took the opposite approach, setting great moral and political store by even the airiest protocols, declarations, directives, and resolutions, using each as a kind of building block. In 1983, Mrs. Thatcher had signed the Solemn Declaration on European Union, because (as she would rationalize from retirement), “I could not quarrel with everything, and the document had no legal force.” The 1984 rebate came at the cost of acquiescence in higher European expenditure, no reform for the Common Agricultural Policy, and agreement to qualified majority voting. Even her attempts to make the E.U. more business-friendly had the effect of locking the U.K. further in—for example, by harmonizing indirect taxes. In 1986, she signed the Single European Act, something she later greatly regretted. As so often, the English underestimated the incantatory power of theories—and the Conservatives displayed a lack of imagination (the principal small-c conservative vice in every country). As on Ireland, Mrs. Thatcher was almost alone in her distrust of the project, with many of her most senior allies affianced to the European idea. The process of joining the Exchange Rate Mechanism continued on her watch, against her instincts but pushed assiduously by most in the Cabinet. (The U.K. joined in 1990, and came crashing out disastrously on 1992’s “Black Wednesday.”) Her outspoken anti-Europeanism had the paradoxical effect of deepening integration, because as Moore observes, “being a sceptic herself, she could marginalise the sceptics: if she said it was all right, who would listen to their objections?”

She remains the only Conservative prime minister who has become an ism, and her rule will always be remembered for deregulation, the selling off of state assets from telephones and airlines to council housing, and the radical Stock Exchange reforms of 1986. Behind the latter lay the ghosts of old resentments, as well as reason. Just before the 1979 election, Mrs. Thatcher had been given a hard time by bankers at a luncheon. When Cecil Parkinson told her, “Don’t worry; they’ll vote for you, and they’ll forget it,” she replied “They may, but I won’t.” The long-term economic effects fall outside the purview of this volume, but the author allows that public share-ownership has never really taken off, that banking liberalization helped cause the credit crunch by creating banks that combined risky investment operations with High Street services, and hints en passant at the direful consequences of the credit revolution. The prudent housewife actually facilitated the personal indebtedness of millions. Yet Moore is surely right that economic liberalization was inevitable anyway because of technology, and that “Getting rich, quick or otherwise, is broadly speaking better for a country than getting poor slowly.”

She will also always be remembered—and reprehended—for her actions during the miners’ strike of 1984, during which the ultraleft Arthur Scargill dragooned the National Union of Mineworkers members to strike against the closure of obviously uneconomic pits. But Scargill made the mistake of not holding a national miners’ ballot when he could have won it. The result was that the miners were divided, with those of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, and Kent mostly working and those from Yorkshire mostly striking. There were violent clashes between strikers and police, and nasty assaults on “scabs,” culminating in the death of a taxi driver killed when concrete was dropped from a motorway bridge onto his car, in which he was carrying a working miner. Mrs. Thatcher was horrified by all this—“Scabs?!?” she exclaimed. “They are lions!” Scargill also refused to make concessions when these might have saved some pits or at least secured mitigation of her policy, and he accepted money from both the Soviet Union and—worst of all—Libya, while that country was funding the IRA. He was, ergo, part of what Mrs. Thatcher dubbed “the enemy within” (a phrase derived from Methodist hymns). His obduracy fed Mrs. Thatcher’s, and she was always going to win (being always fortunate in her enemies). It was a battle that had to be won, but there was huge collateral damage in mining communities, the effects of which can still be felt in the north. As Moore says ruefully, “In the struggle to win the strike, no clarity had ever been reached about what ought to happen after.” The “lions” really were betrayed, and the British coal industry is almost defunct, just as Scargill predicted.

A pet project, the poll tax, would lead directly to her defenestration in 1990. The old property-rates system was indefensible, to the extent that Labour gave the proposed tax an almost free ride through Parliament. The idea was furthermore being pushed by the No. 10 Policy Unit, which saw it as part of an overall drive to make local government slimmer and more accountable. But Mrs. Thatcher, normally so detail-focused, had not considered how big a job it would be to compile new taxpayer registers, nor wondered how those who had never been taxed (including students, pensioners, and the disabled) would feel—or how the tax would be collected. Almost everyone else in the Cabinet was against it, including Chancellor Nigel Lawson, but for once she refused to compromise. Her political secretary Stephen Sherbourne noted sadly, “It was the beginning of her losing touch with people, with a real electoral base.”

Intrigue and interdepartmental turf wars were always impinging upon domestic policies. The Westland affair started off as a minor disagreement about whether an American or a European consortium should take over a British helicopter manufacturer, but escalated into a crisis over which two ministers resigned, and the government could have fallen. A barbed footnote summarizes perfectly the character of Michael Heseltine, a showman who, Moore relates, wore no fewer than six different neckties on the day he resigned. The polite façades of the London SW1 postal district masked mares’ nests, with parts of the party working against each other and their ostensible leader, while other parts would “respond excessively to whatever they thought might be her will.” Looking back, Norman Tebbit remembered that he “began to understand Tudor history better.” Small wonder Thatcher was often indecisive—until she had committed herself to some course of action.

She was part of the problem, because she was no Machiavellian and so was often unaware of what subtexts were seething around her. She rarely flattered or gave public credit to ministerial colleagues, and could be inadvertently rude. At one Chequers meeting, she cut off Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe with, “Don’t worry, Geoffrey. We know exactly what you’re going to say!” Unsurprising that even the urbane Howe could at times explode like “a Welsh hwyl.” And Thatcher was not clubbable; Robin Butler, who was her principal private secretary for three years, likened talking to her socially to “feeding a fierce animal.”

She was exceptionally lucky in some of her officials, like Robin Butler, Charles Powell, and press secretary Bernard Ingham, all of whom combined loyalty and respect for her intelligence with a kind of chivalry. There is a touching anecdote of her private detective seeing her just before an operation on her hand—“how lonely she looked in the hospital, clutching a teddy bear that the Garden Room girls had given her.” Nevertheless, she often felt the need to resort for advice or encouragement to outsiders, raffish characters like David Hart, the Old Etonian Jewish banker and novelist who claimed to know “the street” and have an empathy with coal miners, and the oenophile quidnunc Woodrow Wyatt, who acted as a conduit to Rupert Murdoch and the Royal Family. “She liked dangerous people,” reflected former political secretary Tim Flesher.

And these were her allies. The London N1 postal district sheltered sworn enemies. Like David Hart, but maliciously, a preponderance of the capital’s journalists, playwrights, novelists, filmmakers, and musicians imagined they had a special understanding of life in Brixton, or White chapel, or the mining communities of County Durham. Mrs. Thatcher was not just wrong on facts, they felt, but motivated by varying combinations of classism, cupidity, homophobia, ignorance, philistinism, racism, and selfishness. (It was harder to accuse her of sexism, although that was essayed.) They felt unbounded contempt for her romantic view of English history—what Moore calls her “grand simplicities”—her unpretentious religiosity, and even her hairstyle and clothes. Anthony Burgess sniffed, “She reads best-sellers.”

On her death, the playwright Howard Brenton hyperventilated, “It was as if some kind of evil was abroad in our society, a palpable degradation of the spirit,” while Ian McEwan wrote, “It was never enough to dislike her. We liked disliking her.” Other cultivated haters included Julian Barnes, Jonathan Miller, David Hare, Dennis Potter, Alan Bennett, and Hanif Kureishi, and they were lavished with screen and airwave hours by the BBC, which even gave Doctor Who a Thatcher-like enemy. She was portrayed by cartoonists as cannibal, nuclear cloud, pterodactyl, and shark, and by Spitting Image as an aquiline dominatrix. She was refused an honorary degree by Oxford (she already had a real one), essentially because of what one anti-Thatcher academic called a strong “aesthetic” objection. The snub hurt her but backfired, as American donations to Oxford dried up in consequence.

She was scorned as anti-intellectual, but while it is true that she insisted on pronouncing the t in Godot and thought Alan Hollinghurst’s then-lauded novel The Line of Beauty was called The Line of Duty, part of the problem seems to have been that she listened to those whom leftists saw as the “wrong” intellectuals—Keith Joseph, Alfred Sherman, and Hugh Thomas—instead of to them. One rare academic fan, John Vincent, felt she had become

the point at which all snobberies meet—intellectual snobbery, social snobbery, the snobbery of [London club] Brooks’s, the snobbery about scientists among those educated in the arts, the snobbery of the metropolis about the provincial, the snobbery of the South about the North, and the snobbery of men about career women.

As the 1987 election approached, despite a strong economy, the cumulative abuse grew ever louder and more personal, and the strain became obvious. Moore gives a vivid account of the day one week before polling that would afterward be called “Wobbly Thursday,” when Smith Square witnessed an extraordinary shouting match, the prime minister “almost hysterical,” screaming, her eyes flashing: “hatred shot out of them, like a dog about to bite you,” said one shocked observer. As this magisterial account reaches its too-early end, the once-indefatigable ironclad is seizing up and starting to run to rust, with back-office and backbench restiveness approaching critical levels, the Cabinet losing the habit of collective responsibility, and public opinion tiring at last of what even Tory loyalists called “TBW” (“That Bloody Woman”). She had said during the campaign that she planned to “go on and on,” but for a growing number of people she had obviously gone on long enough already. As she stood at the Downing Street window beside Denis Thatcher and Norman Tebbit on election night, she must have been thinking about her own as well as Britain’s future.

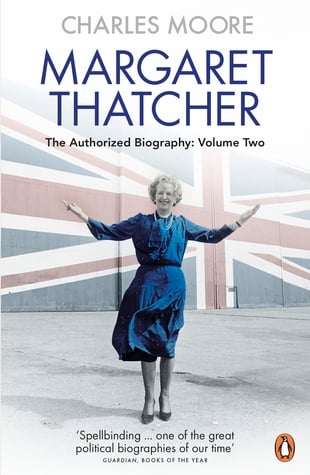

[Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Two—Everything She Wants, by Charles Moore (London: Allen Lane) 821 pp., £30

Leave a Reply