The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero

by Peter S. Canellos

Simon & Schuster

624 pp., $32.50

The luckiest of lovers sleep entwined with each other. Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones slept with his dogs. Any person owned by a house cat often finds it cuddled up close during the night. A colleague of Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan said that Harlan “goes to bed every night with one hand on the Constitution and the other on the Bible, and so sleeps the sweet sleep of justice and righteousness.”

Whether Harlan was a great Justice is a more difficult matter. The author of this very readable biography has no doubts, as he calls the man, in the book’s very title, “The Great Dissenter,” and “America’s Judicial Hero.” We might do well, however, to bear in mind that Canellos is the also the editor of an equally hagiographic biography of Ted Kennedy called, curiously, The Last Lion, which makes the case that Kennedy “transformed himself into a symbol of wisdom and perseverance.”

As one who was not an admirer of the late Senator from Massachusetts, I had low expectations for this biography. As I suspected, Canellos makes clear his disapproval for conservatives generally, for the late Justice Antonin Scalia in particular, and for the theory that Supreme Court justices should follow the original understanding of the Constitution.

Canellos is an editor at Politico and a former editor at The Boston Globe, as well as a graduate of Columbia Law School, and though a journalist, he shares the perspective of most current American law professors, who measure judicial greatness not by a willingness to let the will of the legislator govern, but rather by the judge’s striving to implement his idea of justice and righteousness.

Equally disturbing is that Canellos has few good things to say about the South. He endorses the idea that the Confederacy caused the Civil War and claims that Southerners continued to reintroduce slavery in a new form through Jim Crow laws. His is a Northern and politically correct interpretation of the Civil War and Reconstruction, so he is careful, at least most of the time, not to refer to “slaves” but rather to “enslaved persons,” as is now de rigueur among the woke in the academy and the media.

Having said all that, this is far from a bad book. Canellos is a gifted writer; he is splendid at invoking the atmosphere of 19th and early 20th century America, and he is a more-than-competent constitutional scholar and legal historian.

Most importantly, he has given us a detailed study of an often overlooked legal figure who was profoundly concerned with America’s greatest and most intractable social problem: race. The once slave-holding Justice Harlan’s eventual solution to that dilemma was the same as the one at times advocated by Martin Luther King, Jr., by Frederick Douglass (who was Harlan’s friend), and by Justice Clarence Thomas. That solution was articulated in the one Harlan utterance that is universally still remembered: “Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

The sentence comes from his courageous dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution permitted “separate but equal” treatment of the white and black races. The case involved railroad transportation and the principle of officially permitted racial segregation in this country. Harlan would have none of it. In words that eventually formed the bible for the American Civil Rights movement, Harlan argued that the majority in Plessy was wrong.

Political, legal, and social conservatives have taken Harlan’s color-blind characterization to mean that any official discrimination on the basis of race is unconstitutional. As the current Chief Justice John Roberts stated in a 2007 opinion, “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

It should be noted that for black activist Ibram X. Kendi (author of How to Be an Antiracist) and others who claim the existence of systemic racism and white privilege in America, the color-blind approach is a racist dodge for the avoidance of the necessary reparations and redistribution.

Canellos doesn’t explicitly condemn the views of Kendi and those like him, but his presentation of Justice Harlan strongly suggests that Harlan advocated simply for equality of opportunity—in short, for extending to freed blacks the same full protection of their civil and economic rights as was afforded whites. The best evidence of this is the substantial space that Canellos devotes to Robert Harlan, a man likely to have been the mixed-race half-brother of the Justice.

A third of the book is devoted to Robert and his family, and it is as fascinating as those concerning the Justice. The parallel narrative shows that, at least in the 19th century, a former slave like Robert with good connections and good looks could reach the pinnacle of American accomplishment. By the standards of his age, Robert was a great financial success—the equivalent of a multimillionaire today. Even more interestingly, he was a leader among a rising free black elite and was able to exert enough political influence to aid in securing the appointment of his apparent half-brother John to the Supreme Court.

Canellos uses Robert’s life story to suggest that it shaped Justice Harlan’s color-blind constitutional ideal, that talented African Americans should be permitted—free from discrimination—to accomplish whatever they can. Who could disagree?

More problematic, however, is Harlan’s jurisprudence in practice, which involved the enhancing of the Constitution to make it conform to his sense of righteousness and justice. Legally trained readers might understandably review some of Harlan’s less famous dissents, particularly in matters concerning antitrust and freedom of contract, and conclude that Harlan’s consequentialist approach to the Constitution (believing that it authorized the implementation of the equitable goals he favored) departed from text, history, and precedent.

Indeed, in this regard there are strong similarities between Harlan the Great Dissenter, and Justices Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, who similarly and repeatedly wrote thinly reasoned opinions based more on their notions of just policy than on the Constitution.

In some quarters of the legal academy, scholars have even questioned Harlan’s notion (at least as eventually articulated by Justices Roberts and Thomas) that the Constitution must be color-blind. They have pointed out that the Reconstruction Congress, the authors of the Fourteenth Amendment, clearly passed racially based measures designed to favor the newly freed slaves. Others, such as Raoul Berger, have countered that the Fourteenth Amendment should be construed as seeking only equality of rights, not special treatment for those it sought to protect.

The historical record is ambiguous; thus it is not surprising that Canellos is not persuaded that Scalia’s constitutional jurisprudence of original meaning leads to the correct solutions for constitutional interpretation. Canellos, then, has embraced, as did Harlan, the consequentialist approach to the Constitution now taught overwhelmingly by the liberal and progressive law-school professoriate.

Similarly, Canellos is not troubled by his apparent conclusion that Harlan was a justice influenced as much by family and personal experience as he was by the law. Indeed, it is now generally accepted among American political scientists that a judge’s ideology is a significant predictor of judicial outcomes, notwithstanding Justice Roberts’s dubious 2018 claim that there are no “Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges.”

One would have to subscribe pretty completely to Justice Harlan’s morality, politics, and unique sense of law and justice in order to reach the conclusion that he is “America’s Judicial Hero.” A good paleoconservative jurisprude, committed as was Sir William Blackstone and Justice Scalia to the modest judicial role of following the law already laid down, will not unqualifiedly endorse the work of Justice Harlan, or even the oxymoronic concept of “judicial heroism.”

Whether it was dictated by the Constitution or not, however, a polity in which one’s race does not determine one’s equality before the law is the one we ought to have, and Canellos has done well to demonstrate that at least one justice, even in troubled times, adhered to that ideal. Whether or not it can truly be shown to be mandated by original understanding, a “color-blind Constitution” is more consistent with righteousness and justice than the alternative.

Our problems as a society, however, are more likely to be ameliorated by justices committed to the constitutional structure of separation of powers, so that judges do not make law, and to federalism, in which state and local governments have the primary responsibility for domestic law and policy. By his careful scholarship, Canellos may have inadvertently provided some support for a limited judiciary and separation of powers.

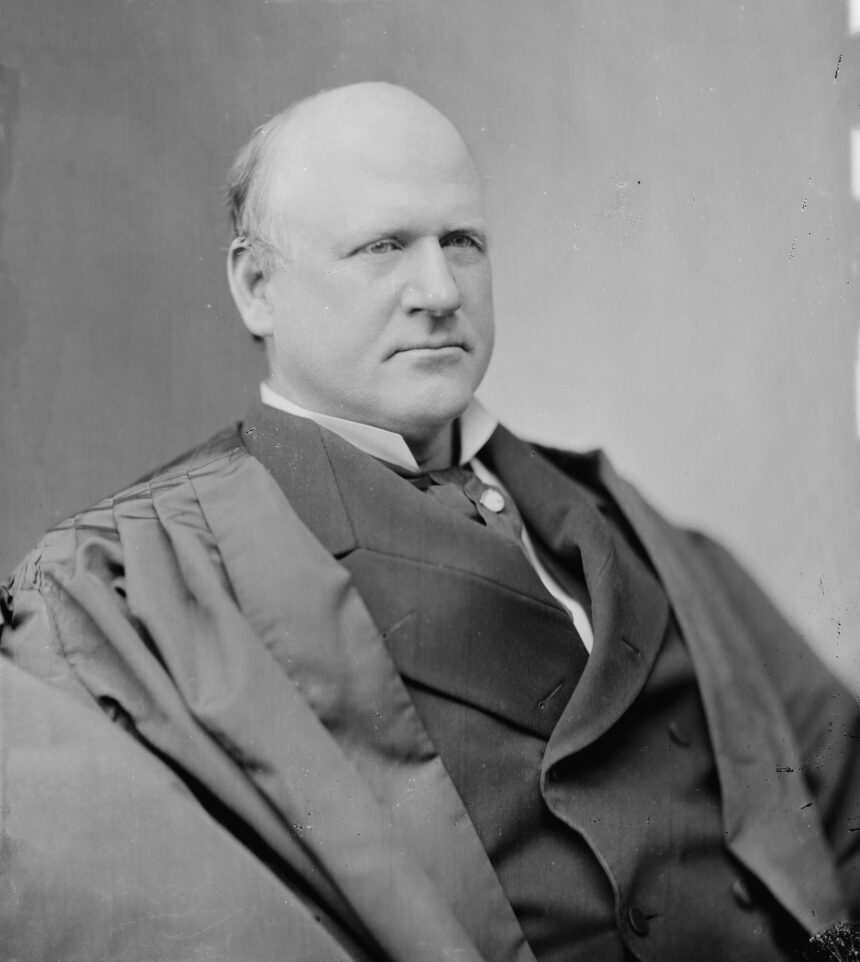

Top image: Justice John Marshall Harlan

(Library of Congress, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection / public domain)

Leave a Reply