Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife; by Bart D. Ehrman; Simon & Schuster; 352 pp., $28.00

Were popular success an index of scholarly mastery, Broadway musical composer Andrew Lloyd Webber would be recognized as a world authority on Christology. He is not, but Bart D. Ehrman is, and his presumptive expertise in the history of religion is on display in his latest book, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife.

In the past 35-odd years, Ehrman has probably written more books on early Christian doctrine than the collective theology faculty of the Sorbonne. As a fawning review in Time magazine points out, several books from Ehrman’s expansive bibliography have made it to The New York Times’ bestseller list. I admit that I harbor elitist misgivings about whether such a feat is evidence of Ehrman’s scholarly attainment.

One need only look at the catchy titles of his best sellers to see why Ehrman is so fashionable and prolific: Did Jesus Exist?; The Other Gospels; Forgery and Counterforgery; Jesus Interrupted; Misquoting Jesus; Lost Christianities; The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture; and Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code.

These titles encapsulate the groundbreaking revelations that have propelled Ehrman’s scholarly oeuvre to the eyries of best-sellerdom: that a merely human Jesus existed, but that the canonical Gospels “interrupted” and “misquoted” him; that there were other, no doubt more authentic gospels and “Christianities” deliberately suppressed by the Church hierarchy, whose orthodoxy “corrupted” Scripture; and that Dan Brown is—at least partly—to be taken seriously. With the exception of the Brown Codex, all of this is about as “new” as the field of biblical scholarship known as higher criticism and its eternal “search for the historical Jesus.”

Like that of Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, and the rest of the New Atheists, Ehrman’s “scholarship” is harnessed to the project of proving that orthodox Christian doctrine is inauthentic, childish, deceitful, and malevolent. This project always advances by means of scholarly “discoveries” about Christianity (the Pentateuch wasn’t written by God or even Moses but by four different human authors; the Gospels disagree!), as if Christian theologians and educated laymen haven’t known about them for centuries.

Unlike the cradle atheists, Ehrman feels entitled to trade on his status as a former believer in order to assure his readers of the fair-mindedness of his critique. But from his description of his as-yet-unredeemed self as a “liberal Christian,” we might well suspect that the seeds of enlightened doubt were already gnawing at his conscience in the baptismal font. Rather too much of Heaven and Hell, and Ehrman’s other books, is tiresomely autobiographical; an account, not of ancient and early Christian eschatology, but of the heroic quest by which the author progressed from credulous certitude about the existence of heaven and hell, to the mature awareness that the admonitory tale that had frightened him into obedience to Mother Church as a child was, well, forged.

Thus he laments that, as a born-again youth, he at first “had no doubt: I was going to heaven.”

“I was equally convinced that…most of the billions of other people in the world…were going to hell,” he continues.

I tried not to think I was being arrogant. It was not as if I had done something better than anyone else and deserved to go to heaven. I had simply accepted a gift. And what about those who hadn’t even heard about the gift…? I felt sorry for them. They were lost, and so it was my obligation to convert them.

Here one already catches two of the sneering assumptions that resound throughout the book. The first is the calumny that the Christian intellectual tradition is hopelessly mired in literalism. In fact, it is well-known that it was born in an allegorical revolution against Jewish literalism. The second is the charge that Christian tradition is inhumanly arrogant and sectarian in condemning nonbelievers to eternal torment in hell. It is also well-known that such had never been the case: the stricture extra Ecclesiam nulla salus (“Outside the Church there is no salvation”) did not apply in the case of the patriarchs, pagan worthies, unbaptized dead, and even “ignorant” heretics, ever since the Patristic Age.

Ehrman reports that at the Princeton Theological Seminary, his “scholarship led [him] to believe that the Bible was a very human book,” with “human…biases and culturally conditioned views,” and the Church’s beliefs in God and Christ “were themselves partially biased, culturally conditioned, or even mistaken.” Ehrman also “discovered” there that doctrines such as the Trinity, the divinity of Jesus, and his Resurrection, weren’t “handed down from heaven,” but were late “inventions” and fallible human formulations.

And then occurs Ehrman’s agony in the sauna. Noticing that, “It sure is hot in here! Oh, man, is it hot in here!,” his spirit perspires over whether he really wants “to be trapped in a massively overheated sauna for all eternity” as a consequence of changing his beliefs. At that incandescent moment, Ehrman sets out on his journey to enlightenment.

Ehrman’s book is made unreadable by its repletion with similarly infantile locutions, and the condescending implication that the great minds of the Christian theological tradition—Origen, Augustine, Boethius, Dante, Thomas Aquinas, Marsilio Ficino—not to mention the minds of his readers, are as reductively puerile in their understanding of the afterlife as is his own.

Thus Ehrman has the effrontery to announce in his preface that, “One of the surprising theses of this book is that [Christian beliefs about heaven and hell] do not go back to the earliest stages of Christianity,” nor can they “be found in the Old Testament and…are not what Jesus himself taught.” Surprising? Who does not already know that the New Testament sometimes superannuates the Old and that Christian doctrine is a plant that germinates from apostolic seeds?

How can Ehrman proclaim this as his “thesis” when thousands of books, going back to the Church Fathers themselves, have already acknowledged it? None of those authors have found it particularly controversial that not all of the Church’s teachings come fully formed from the mouth of Jesus, nor are they quite as avid as Ehrman to amputate a living tradition that has lasted for 2,000 years.

Yet we are supposed to be surprised that other religions too “were remarkably diverse in their views” about the afterlife, that “even within the New Testament” Jesus, Paul, and the Evangelists “promoted divergent understandings.” All of this leads to the conclusion that the Church’s teaching about the afterlife is “late” and therefore spurious—assuming that the Church’s teaching ever coalesced into the concretistic, monolithic caricature of heaven and hell that Ehrman erects as his straw man.

Yet we are supposed to be surprised that other religions too “were remarkably diverse in their views” about the afterlife, that “even within the New Testament” Jesus, Paul, and the Evangelists “promoted divergent understandings.” All of this leads to the conclusion that the Church’s teaching about the afterlife is “late” and therefore spurious—assuming that the Church’s teaching ever coalesced into the concretistic, monolithic caricature of heaven and hell that Ehrman erects as his straw man.

Here is how the consoling Christian fable was “invented.” Neither Homer nor the writers of the Old Testament had anything but the vaguest notion of an even more vaporous existence in the afterlife, but people came to think “this could not be right…because it was not fair.” Men yearned for some compensation for the hardship, misery, and injustice of their earthly lives, some assurance that vengeance would be visited upon their enemies, and that right would eventually prevail. Thereupon arose the Jewish expectation of a general resurrection at the end time, and the earthly restoration of Israel “as a sovereign state.”

This is the view proclaimed by Jesus of Nazareth: Those “who did God’s will would be rewarded at the end, raised from the dead to live forever in a glorious kingdom here on earth.” (Accordingly, forget Jesus’s seminal rebuke to the Pharisees in the Gospel of Luke, “The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.”)

When the end time, assumed to be imminent, wasn’t, Ehrman explains, “some of [Jesus’s] followers came to think that God’s vindication of his followers would not be delayed until the end of human history,” but “would happen to each person at the point of death.” Thus “heaven and hell were born.”

Fortunately for Christianity, the real inspiration of its doctrine of the afterlife is more complicated than Ehrman’s pop-psychological explanation for the Hebrews’ feelings of unfairness and early Christians’ impatience. Heaven and hell were hardly born at this late juncture, but were already thousands of years old. The immortality of the soul and a retributive afterlife were concepts repeated in the myths of the Egyptians, the Persians, the Greeks, and the Romans, all of which were not “remarkably diverse,” as Ehrman asserts, but remarkably universal, and all of which the Christian apologists and Church Fathers knew and regarded as analogous to or prefigurative of their own teaching.

The proximate influences upon early Christian eschatology were the myths and dromena of the Orphics, the Pythagoreans, Plato, Cicero, Virgil, Apuleius, the Middle Platonists and Neoplatonists, the Hermetic corpus, and the mystery religions of Eleusis, Isis and Osiris, Mithras, and Hercules. But Ehrman scarcely mentions them, save for the dozen-odd pages in which he disposes of the Platonic dialogues in which the subject of the afterlife is front and center.

In short, Ehrman’s book is a history of the afterlife in the same sense that Mel Brooks’ cinematic farce is a History of the World.

The whole purpose, of course, of Ehrman’s perfunctory survey is to demonstrate that the Christian belief in the immortality of the soul and its hoped-for rewards in heaven and dreaded torments in hell is a neoteric confabulation, a theological aberration, and therefore not to be taken seriously—notwithstanding that even the thin historical gruel he provides contradicts his own thesis. But no review would be long enough to catalogue its omissions, not to mention its errors of fact, including the stretchers that Socrates actually believed in the soul’s extinction at death, and that Jesus and Paul made no construable reference to a postmortem heaven or hell.

The Church’s teachings on heaven and hell have indeed been various, wide ranging, and sometimes contradictory: from the literal fire and brimstone of Protestant fundamentalism, to the spiritualizing interiority of a Christopher Marlowe (“Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib’d…”) or a John Milton (“The mind is its own place, and in itself…”). But Christian doctrinal plenitude is a cause for rejoicing, not repining; not an indictment of the risible falsity of Christian belief, but an acknowledgment of the ineffable mystery it vainly gropes toward: that the invisibilia Dei are, as Plato said in the Timaeus, “beyond knowing or expressing,” never to be reduced to crude concretisms yet at the same time representable only through the visible shadows and analogies necessary to accommodate the limits of the human imagination.

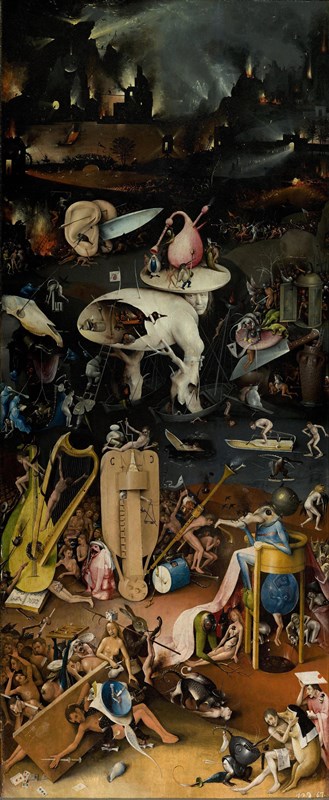

The book’s other purpose is to show how embarrassingly illiberal and unmodern all the traditional Christian postulates of sin, heresy, damnation, and eternal punishment are, the most lurid descriptions of which Ehrman lovingly details from the literature:

Do you want to spend eternity hanging by your genitals over eternal flame, standing in a deep pit up to your knees in excrement, having your flesh perpetually shredded into pieces by ravenous birds? Or do you want to luxuriate in a lovely garden with the pleasant smells and cool breezes of eternity wafting over you…? You get to choose.

Thus does Ehrman anatomize the darkly manipulative agenda of one early Christian account of the afterlife. In another, The Acts of Thomas, the author fulminates benightedly against lust, and retails the gruesome tortures to which those vaguely guilty of it are promiscuously sentenced. Thomas warns that, for the unrepentant, there are even worse punishments.

“Worse than these?” our author editorializes. “How could they be worse than these? Apparently they are.” Alas, as Ehrman laments, early Christians appear to have taken such grisly descriptions literally, and many Christians still do. They are terrorized “to behave now…in the belief that there will be torments later for those who misbehave.”

Conversely, Ehrman bemoans the example of St. Perpetua and all others since, who are willing to “throw away” their lives for their faith “so they can be rewarded afterward.” For Ehrman, it is apparently inconceivable that the archetypal mythos of an afterlife could be rooted in anything more profound than a personal craving for reparation or revenge, the Church’s anxiety to keep the flock in the fold, or society’s need to ensure that citizens don’t “misbehave.”

The heavy hand of Ehrman’s modernist moralizing thus strangles his “scholarship” in its crib. A scholarly treatment of early material requires some natural sympathy for it; yet Ehrman is capable only of mockery. Indeed, the moral is announced preemptively in his preface. Liberated from our childish hopes and terrors, we will know that “we have absolutely nothing to fear,” and “this assurance, on a practical level, can free us to appreciate and enjoy our existence in the here and now, living lives of full meaning and purpose in the brief moment given us in this world of mortals.”

How glibly and with such primitive fideism does the modern mind accept the gospel of present mirth! The totalitarian horrors of the post-Christian 20th century might have brought to such a mind Dostoyevsky’s admonition that “If God doesn’t exist, everything is permissible,” and induced at least a moment’s consideration of the ethical utility of “scaring the hell out of people,” Ehrman’s typically reductive and juvenile phrase.

And what about giving life meaning? As Jung observed long ago, the expectation of an afterlife has always been central to that primordial psychological need, a hope without which mortal life is more or less akin to painstakingly building a house, brick by brick, floor by floor, knowing that one won’t survive long enough to settle in.

Ehrman scants these perennial philosophical problems, just as he seems to be entirely innocent of the theme—rehearsed by Platonists, Stoics, and Christians alike in every century—that no “happiness,” properly understood, can be founded in the possession of earthly joys and pleasures, since at the very height of their enjoyment, one’s contentment is subverted by the knowledge that they are mutable and transitory.

Leave a Reply