“Poetry requires not an examining but a believing frame of mind.”

—T.B. Macaulay

In the United Kingdom, back in 1997, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings was voted “the greatest book of the twentieth century” in several major polls, emerging as a runaway winner ahead of its nearest rival, Orwell’s 1984. Tolkien was also voted the 20th century’s greatest author, ahead of Orwell and Evelyn Waugh.

Tolkien’s triumph was greeted with anger and contempt by many literary “experts.” Writer Howard Jacobson reacted with splenetic scorn, dismissing Tolkien as being “for children . . . or the adult slow.” The poll merely demonstrated “the folly of teaching people to read . . . It’s another black day for British culture.” Susan Jeffreys wrote in the Sunday Times that it was “depressing . . . that the votes for the world’s best 20th-century book should have come from those burrowing an escape into a nonexistent world.” The Times Literary Supplement described the results of the poll as “horrifying,” while a writer in the Guardian complained that The Lord of the Rings “must be by any reckoning one of the worst books ever written.”

Probably the most bitter response to Tolkien’s triumph came from feminist writer Germaine Greer, who, a quarter of a century earlier, had attained notoriety for her authorship of the best-selling handbook of women’s “liberation,” The Female Eunuch. Greer complained that

Ever since I arrived at Cambridge as a student in 1964 and encountered a tribe of full-grown women wearing puffed sleeves, clutching teddies and babbling excitedly about the doings of hobbits, it has been my nightmare that Tolkien would turn out to be the most influential writer of the twentieth century.

Rarely has the vitriol of the critics highlighted to such an extent the cultural schism between the literary illuminati and the views of the reading public.

Most of the self-styled “experts” among the literati who queued up to sneer so contemptuously at The Lord of the Rings are outspoken champions of cultural deconstruction and moral relativism. It is also noteworthy, however, that their anodyne and anoetic criticisms of Tolkien’s work betrayed an utter ignorance of the profound debt to, and depth of, Christian theology that is its chief hallmark. No doubt, had they been less ignorant, they would have sneered with an added degree of derision at the discovery that the work was deeply Christian in inspiration. Either way, the level of critical engagement, or lack thereof, illustrated a collective blindness regarding the Christian dimension in The Lord of the Rings.

My exasperation at this blindness was the spark of motivation behind my writing of Tolkien: Man & Myth (Ignatius Press, 1998). My intention was to highlight the centrality of the Catholic Church in Tolkien’s life and to illustrate the significance of the author’s Catholicism to his work. Previously, the major critical works on Tolkien—those by Tom Ship-pey and Verlyn Flieger—had concentrated on the linguistic dimension, while largely overlooking the religious aspects. Although these scholarly studies were excellent and worthy of the highest praise, the fact remained that the most important ingredient in Middle Earth was not being discussed.

Tolkien insisted that the fact that he was “a Christian (and in fact a Roman Catholic)” was the most important of the “really significant” elements in his work, stating specifically and explicitly that it was more important than the linguistic influence. On another occasion, Tolkien wrote that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work: unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.” This being so, it seemed odd, to say the least, that there had been no major study of the real significance of the Catholicism of The Lord of the Rings. My own work was an effort to rectify a sin of omission.

Now, however, five years after the publication of my book, there seems to be a veritable flood of new religious studies of Tolkien. It is not, perhaps, a plethora, since that suggests that the new phenomenon is in some respects unwelcome or unhealthy; rather, it is an embarrassment of riches. I am utterly delighted that there is now such a flow of Christocentric studies of “the greatest book of the 20th century” and would like to offer a brief guide to some of these titles.

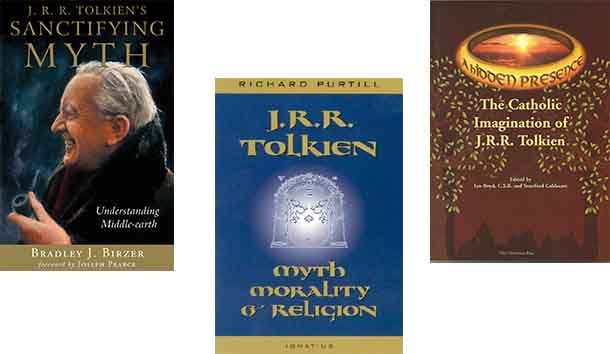

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, by Bradley J. Birzer, is the pick of the crop. In chapters on “Myth and Sub-creation,” “The Created Order,” “Heroism,” “The Nature of Evil,” and “The Nature of Grace Proclaimed,” Professor Birzer elucidates the sheer magnificence of Tolkien’s mythological vision and the Christian mysticism and theology that vivify it. The highlight of the book is an excellent and enthralling chapter on the relationship between Middle Earth and modernity, in which Professor Birzer combines his scholarship as an historian steeped in the tradition of Christopher Dawson and Russell Kirk with his grounding in philosophy and theology to place Tolkien’s sub-creation in its proper sociopolitical and cultural context.

If Birzer’s book has a rival, it is Richard Purtill’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality and Religion. This is not merely my opinion but that of Professor Birzer himself. “Purtill’s book deserves a place along side the best of Tolkien criticism,” Birzer writes.

At once deeply personal, wise, and Christian, Purtill’s intellectual and highly readable work offers an overflowing stream of brilliant insights into Tolkien the man, the author, and the Roman Catholic. Especially stunning are Purtill’s explorations of myth and the deeper meanings behind serious science fiction and fantasy. One comes away from this book not only with a better understanding of Tolkien, but more importantly, with a greater grasp of truth, beauty, and Grace.

The best of the rest is A Hidden Presence: The Catholic Imagination of J.R.R. Tolkien, a selection of essays edited by Fr. Ian Boyd, better known as a stalwart Chestertonian than as an aficionado of Tolkien, and Stratford Caldecott, Father Boyd’s colleague at the Chesterton Institute. Calde-cott is a Tolkien scholar of rare insight whose salience and sapience on the typological significance of myth is particularly penetrative. Other essays in this volume include Owen Dudley Edwards on “Gollum, Frodo and the Catholic Novel,” which endeavors, not always entirely successfully, to forge critical connections between The Lord of the Rings and the novels of such Catholic writers as Mauri-ac, Bernanos, Greene, and Waugh. Clive Tolley’s essay on Tolkien’s sadly underrated and underread poem “Mythopoeia” is engrossing but flawed by Tolley’s misreading of Pope’s Essay on Man. Dwight Longenecker’s essay comparing hobbit humility with the humility of St. Therese of Lisieux is full of the succinct ingenuity I have come to expect from his deftly adroit pen.

Perhaps the finest essay in A Hidden Presence, at least in terms of the pure quality of the prose, is Leonie Caldecott’s “At Dawn, Look to the East,” which is as fresh and as bright as the dawn itself. The low point is the contribution by veteran Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger. At times, her sociological reductionism reduces her analysis to the level of the inane, and she apparently has no conception of the theo-logical depths from which Tolkien drew his inspiration. Her claim, for instance, that Tolkien’s history in Middle Earth “begins in imperfection” is curious, to put it mildly, considering that Tolkien’s history begins with God! Her essay is so patently contradicted by the general consensus of the other contributors to the volume that it protrudes from the pages of the book like a sore thumb.

There is much else that is good in A Hidden Presence, not least of which are several “Perspectives” by those who knew Tolkien personally, including George Sayer and Robert Murray, S.J. There is also an excellent essay entitled “Insights About Evil in The Lord of the Rings” by the exceptionally gifted scholar and wordsmith Peter Kreeft, which was originally published in the Saint Austin Review

(www.saintaustinreview.com), a Catholic cultural journal of which I am coeditor.

Space does not permit more than a cursory glance at some of the other Tolkien books that have been published recently. The appropriately named Inkling Books of Seattle has published Celebrating Middle-earth: The Lord of the Rings as a Defense of Western Civilization, a collection of essays edited by John G. West, Jr., as well as Untangling Tolkien, by Michael W. Perry. The former includes contributions by West, Kreeft, and myself; the latter is described as “a chronology and commentary for The Lord of the Rings” and serves as a very useful reference work for those desiring a clearer picture of the time frame within which the action takes place.

There are also several new studies by Protestant critics. These include Tolkien in Perspective, by Greg Wright (VMI Publishers, 2003); The Gospel According to Tolkien, by Ralph C. Wood (West-minster John Knox Press, 2003); Finding God in the Lord of the Rings, by Kurt D. Bruner and Jim Ware (Tyndale House Publishers, 2001); and Tolkien’s Ordinary Virtues: Exploring the Spiritual Themes of The Lord of the Rings, by Mark Eddy Smith (Intervarsity Press, 2002).

For my final selection, we shall turn to Poland, from whence an excellent work of scholarship, Recovery and Transcendence for the Contemporary Mythmaker: The Spiritual Dimension in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien, by Christopher Garbowski (Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press, 2000) is published. In spite of its clumsy title, its scholarly approach and unifying thesis make worthwhile the difficulty of acquiring it.

The quantity and quality of Tolkien scholarship has certainly come a long way in the five years since I felt impelled to gatecrash the ominous silence on the subject. Since then, in the wake of the film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, we have seen how the Peter Jackson entourage has sought to downplay the importance of Tolkien’s Catholic faith in its effort to market its product in a global secular environment. No matter: It is too late to subdue the rising tide of Christian Tolkien scholarship. The proverbial cat is out of the bag; or, rather, the Catholic is out of the Baggins.

[J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, by Bradley J. Birzer (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books) 245 pp., $24.95]

[J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality and Religion, by Richard Purtill (San Francisco: Ignatius Press) 207 pp., $13.95]

[A Hidden Presence: The Catholic Imagination of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Fr. Ian Boyd and Stratford Caldecott (South Orange, NJ: The Chesterton Press) 185 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply