Longlegs

Directed and written by Osgood Perkins ◆ Produced by Nicolas Cage and Saturn Films. ◆ Distributed by Neon

Horror movies are bigger than ever. In a recent stand-alone section of the Sunday edition of The Washington Post, film critic Jen Yamato announced that “in our frightening times, horror movies have met the moment.” The horror genre has doubled its market share since 2013. Movies like The Conjuring, Watchers, It, Longlegs, and Hereditary make huge profits for studios and do so with comparatively small budgets.

Movie critics who dissect horror’s renewed popularly break it down—as Yamato does—into three main genres: “trauma and PTSD horror,” “slasher horror,” and “camp-adjacent fun horror.”

What Yamato and most secular horror critics struggle to realize, however, is that horror films are one of Hollywood’s last bastions for conservatism and religious orthodoxy.

The Post’s special horror section barely mentions Satan, for example. Yet if you examine these films, Satan is ubiquitous. So is this recurring conservative, religious message: evil is real; sin has consequences; and you will regret messing with natural law.

Starting with Frankenstein and Dracula and going all the way through The Exorcist, Carrie, Re-Animator, Hell House, Hereditary, Talk to Me, and Longlegs, the messages of horror films often reinforce positive social norms and warn against violating them. Greed, lust, and pride get punished; so do crimes, violations of God’s natural order, and playing with occult forces.

Frankenstein is a film that explores a perennial horror theme established even earlier in literature, notably in Goethe’s Faust: the danger of playing God by trying to reverse the inevitability of death. Countless horror films punish those who grasp at immortality and refuse to accept the shedding of their mortal coils.

The Exorcist teaches us to not dabble with demons, as the possessed child Regan had done by using an Ouija board. The 2016 film Ouija: Origin of Evil uses one of the oldest horror tropes: a portal opening that allows evil to enter into our world.

In slasher series like Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, and I Know What You Did Last Summer, the kids who get killed off are drunk, promiscuous, or mean. In other words, just like in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, bad kids get punished for their sins.

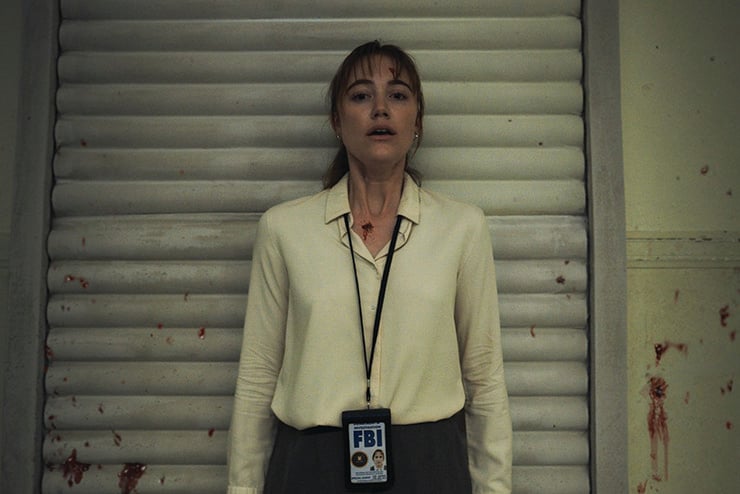

One of this year’s horror hits is Longlegs. FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) and her fellow agent Carter (Blair Underwood) are trying to solve a series of linked family murder-suicide cases that have occurred over decades, known as the “Longlegs” murders. In each of these horrific crimes, the father kills the family, then himself. At each murder scene, investigators find a puzzling note written in satanic symbols and signed “Longlegs.” Yet there is never any evidence that anyone other than the fathers were responsible for the killings.

Somehow, this Longlegs, whatever it is, is making them do it while not being there himself. It probably won’t come as a shock to discover that Longlegs does all of this with the help of the devil—a literal character who appears on screen. Secular-minded film critics can try all they like to layer on psychological, metaphorical, or cultural analysis about American history and the Salem witch trials, but this is what horror films come back to again and again: The devil is real.

Yes, as is so often the case with horror films, Longlegs is a warning about the reality of the devil and the existence of evil. Yet it also hits on the theme of the danger of violating natural law in its eponymous villain, a transgender “woman” played by Nicolas Cage. Liberal critics have wrestled with this, tried to explain away, or denied it, arguing that Cage is not playing transgender at all. Nonsense. Costumed in a white wig, face powder, and lipstick, Cage’s character looks like a Nordic Caitlyn Jenner.

Once again, horror is willing to go where liberal secular America will not: It is saying that there is something inherently evil and freakish about contaminating the natural order of the sexes. Those who try to mock that order by dressing up as the wrong sex are a danger to themselves, to us, and especially to children.

I made this same point in a review of another great horror film, Sinister (2012). With its ghoulish-looking antagonist caked in makeup and coming after kids, Sinister, I wrote, foreshadowed drag queen story hours.

Naturally, I was blasted for “transphobia” by the left. “The reality is that it is no more demonic for children to be read to by a drag queen than it is for children to see a traditionally staged Shakespeare performance with all male actors,” a critic wrote. “Judge is cuckoobananas, and is seeing demons everywhere.”

Not only am I not bananas, I am far more attuned to the true air of horror than mainstream critics. In a July opinion piece for CNN titled “It’s time more horror films push back against queer stereotypes,” far-left critic Noah Berlatsky struggles with the “transphobia” of Longlegs.

The film is an elaborate, bizarre deflection. Cisgender men commit horrific patriarchal violence against their families—but, the movie assures us, they are not to blame. Instead, the horror is stranger danger in the form of a queer-coded, gender-ambiguous villain. It’s as if [director Oz] Perkins started out with a script that engaged with a real, ugly truth about a terror at the center of many ‘normal’ families, and then, panicked, rushed back to the safety of genre tropes.

Rushed back, in other words, to reality.

Horror movies don’t get the critical respect of dramas or even superhero movies, but in some ways they are the most daring kind of storytelling. And, unlike other genres such as action or romantic comedies, horror films are allowed to be unpredictable. Major characters the audience gets to know and care for are suddenly and ruthlessly killed. In The Exorcist, the leading character, a priest, dies during the ritual. In Drag Me to Hell, a young woman who was heartless to a poor old woman gets sucked into hell by demons. In Sinister, Ethan Hawke’s character, a writer, realizes that he has admitted a demon into his home by becoming fascinated by grisly movies—but he realizes too late to save his own life. Longlegs also follows this tradition of unpredictability.

It’s worth noting that Oz Perkins, the film’s writer and director, is the son of actor Anthony Perkins, a screen legend thanks to his role in Psycho, where he played a killer who dressed as a woman. Anthony Perkins died from complications of AIDS in 1992.

In Longlegs, we see the horror genre becoming more conservative even as mainstream Hollywood goes further left. American horror movies can generally be separated into two eras: the pre-revolutionary era before the 1960s and the post-revolutionary era since that eventful decade. Pre-revolutionary films had a common theme: a supernatural threat is introduced into the community and ultimately is put down by religious and civil authorities. The Blob, The Thing From Another World, Dracula, Frankenstein, and other classics all depict an outside force of evil being met and put down by faith, civil authorities, and/or rational and scientific knowledge. (Science, however, is often shown to be a double-edged sword that often causes the appearance of the monster.)

By the late 1960s, horror was a cliched genre reserved for drive-in theaters and exploitation houses. Then maverick filmmakers such as Wes Craven, Roman Polanski, John Carpenter, and Brian De Palma revolutionized the genre. As New York Times horror expert Jason Zinoman writes in his book Shock Value, these directors succeeded by “exploding taboos and bringing a gritty aesthetic, confrontational style, and political edge to horror.” Their films included Rosemary’s Baby, Carrie, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, and The Thing, Carpenter’s remake of The Thing from Another World. This new kind of film “dispensed with the old vampires and werewolves and instead assaulted audiences with portraits of serial killers, the dark side of suburbia, and a brand of nihilistic violence that had never been seen before.”

In these new horror films, authority figures were no longer reliable and the forces of evil either win in the end or achieve a stalemate. Two landmarks of this are Rosemary’s Baby and Night of the Living Dead, both released in 1968. In Rosemary’s Baby, the older generation is shown as not just pushy and arrogant but literally wicked and poisonous. The virtuous protagonist cannot defeat evil in the end, and capitulates. In Night of the Living Dead, authority completely breaks down. As horror historian Kim Newman notes, “Love, the family, military capability, and individual heroism are all useless … horror film heroes have become morally neutral frontline troops, able to understand neither the enemy nor their superiors.” Newman adds that, “Ever since [Night of the Living Dead], movie characters have been caught between the monsters and the reactionaries.”

In recent years, however, traditional horror themes and less morally ambiguous plots are making a comeback. A remake of Nosferatu, the original 1922 vampire classic, is being released in time for Halloween. The pure good-versus-evil tale of Dracula never completely went away, nor did haunted houses, werewolves, demons, or the devil himself. Hollywood can’t kill what human beings know in their souls. Evil is real, there is a natural law, and there will always be something weird, creepy, and even demonic about a man dressed as a woman.

Leave a Reply