This novel inevitably invites comparison with Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints (1973), published in France, as the English equivalent of Raspail’s famous book. The comparison is apt, so far as subject and politics go. But that, really, is the end of it. The Camp of the Saints describes the invasion of southern France by a flotilla of rusted hulks laden below the Plimsoll mark by tens of thousands of refugees from the slums of Calcutta; Sea Changes has to do with the arrival of a single Iraqi immigrant on the east coast of England. Raspail’s novel, reflecting the scale of the imagined event, has the scope of epic poetry and a metaphorical vision that deliberately exceeds the limits of probability, while Mr. Turner’s story is an entirely plausible fictional event exaggerated only slightly for his satirical purposes.

Not a great many critics and other writers of nonfiction have navigated successfully the boundaries that demarcate the two literary forms. Right from the start of his book, Mr. Turner laid my apprehensions to rest. It has been a long while since I read a contemporary novel with so much pleasure, involvement, attention, anticipation, at times delight, always interest, and in many places sheer admiration, as I did this one. Sea Changes is a promising debut, and I am confident that Derek Turner’s next novel (and I certainly hope there is to be one) will afford him the opportunity to work through the remaining lapses and uncertainties in language and technique that beset every essayist determined to master the craft of fiction.

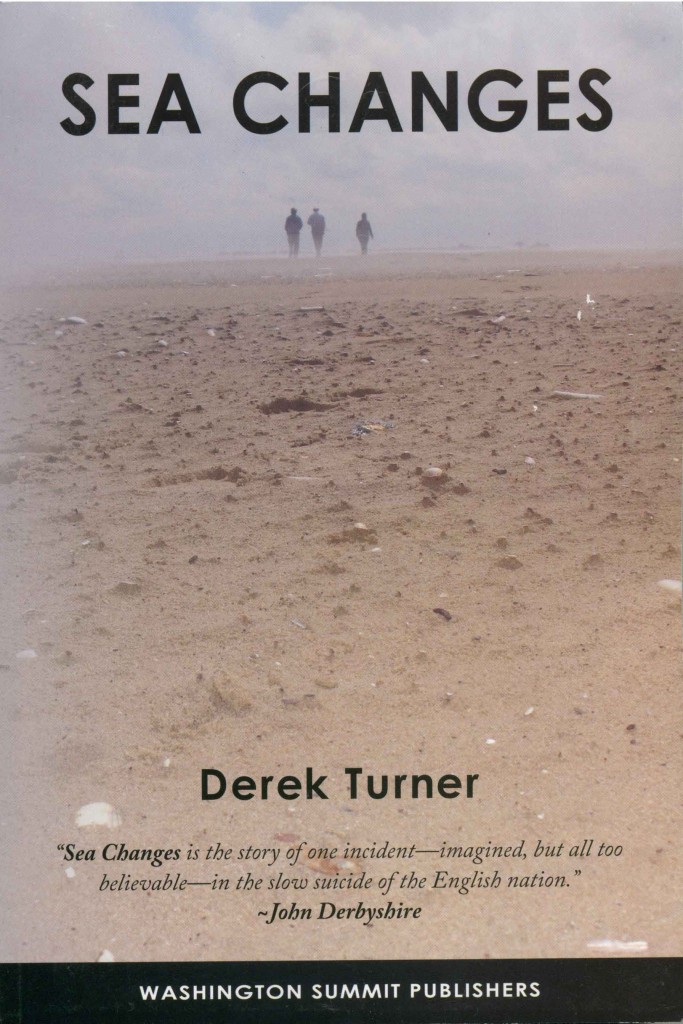

The story’s precipitating incident is the discovery by the local constabulary of several dozen colored bodies on an English beach, possibly drowned but suspiciously perforated by bullets. Two converging narratives ensue: Ibraham Nassouf’s surreptitious journey over land and sea from Iraq toward England, and the development of journalistic and political events in that country, sparked by the instantaneous and unshakable conclusion drawn by media reporters and commentators that the dead must be the victims of racist troglodytic English locals who confronted the immigrants during the night and barbarously slaughtered them. These stories develop apace in alternating chapters to collide finally in a bonfire of the journalistic vanities and an eruption of political idiocy, cowardice, and hypocrisy that do not obscure genuinely poignant elements.

The novel’s best writing occurs in Ibraham’s chapters, as the young man makes his way from Basra to Turkey by train, by boat to Greece, and then north to Rotterdam, concealed, with other illegal immigrants, in a secret compartment inside a refrigerator truck. I do not know whether the author has visited the territories he so poetically describes, but from his descriptions of them one might easily infer that he has traveled the route himself, meticulously recording his observations and impressions in a pocket notebook. On the other hand, the English chapters—which have to do principally with the career of a repellent London columnist who is first and foremost what the English call a prat and only secondarily a toady to the politically correct London establishment—contain some truly lovely passages depicting still-unspoiled rural England whose traditional beauty, effectively grasped by Turner, is lost entirely on the self-consciously adventuresome gentlemen and ladies of the media venturing forth from London to peer into England’s atavistic heart of darkness, county seat of the Horror.

Unlike The Camp of the Saints, where Raspail reserves authorial sympathy chiefly for Professor Calguès—the philosophical avatar of European civilization, sitting down to a simple but elegant French repast that may well be his last supper, while he awaits the dark hordes swarming on the beach below his house—Sea Changes balances fierce satire with considerably warmer tones. Ibraham is no stock character in a restrictionist’s nightmare. He is a child of the God unknown to himself, to his people, and to his religion. Ibraham is understandable in his motives and in his actions, and rather likeable; in moments of crisis, even admirable. Yet Turner never allows sympathy to compromise stern understanding. The allure Europe holds for Ibraham is not, ultimately, political, social, or even economic; it is sexual. Well acquainted with Western films, mooning over lovely blondes in fine clothes (or no clothes) taking their ease in what to him are palatial dwellings, he dreams of indulging himself in the sexual hedonism of post-Christian civilization. While he is being fêted in England as the sole survivor of a cargo of immigrants put overboard and shot by an Albanian smuggler eager to escape from an approaching English coastal-patrol boat, Ibraham dishonestly represents himself to the media as a political refugee, a former political dissident against Saddam Hussein’s regime. Although this initial lie was an involuntary one, Ibraham never recants. Eventually, he is found out—to the utter disregard of the London media, who now insist that, however disingenuous the young man may be, he is worthy nevertheless of asylum for the trials and tribulations he has experienced. (Rather like the sufferings that endeared Othello to Desdemona, one imagines.)

The book’s pathos lies in Derek Turner’s imaginative apprehension of the confusion and suffering political correctness causes ordinary Britons caught between the reality of the world as they know it to be and the unreality of the ideological construct imposed upon them by the “educated” governing class, accompanied by the demand that they conform their thoughts as well as their behavior to it. Subject to minute and ceaseless surveillance by the guardians of multicultural Britain alert to every ideological faux pas, every involuntary or unguarded remark, they experience the humiliation of seeing their faces projected on the evening news and the political talk shows, and hearing themselves make perfectly commonsensical remarks for which they are subsequently mocked and derided by media hosts and commentators and threatened by anonymous callers promising mayhem against the “racists.” When even their families seek to distance themselves from the offenders, they wonder whether it is possible that the common beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions in which they were raised might not after all be shamefully—not to mention criminally—wrong. Such is the condition of ordinary unregenerate man in the reign of multiculturalist liberalism.

Contrary to what contemporary Western establishments think, this ordinary man is not, in his natural loyalty to his own people, his own religion, his own culture, his native country, morally and intellectually atavistic, stunted, twisted, and sick. He is, indeed, splendidly sane and whole, robustly healthy, his best instincts intact together with his common sense. Not he, but advanced liberalism is perverted and sick. Multiculturalism is an intellectual and a spiritual illness. It is also a dangerous social disease, a pervasive syphilitic ideology that rots the brains and destroys the central nervous systems of the societies it attacks. Derek Turner observes the progress of this disease and demonstrates its dreadful personal and social effects as well as any writer, expository or novelistic, I can think of. His mordant tale is enough to make the reader ashamed of having enjoyed this book so much.

Leave a Reply