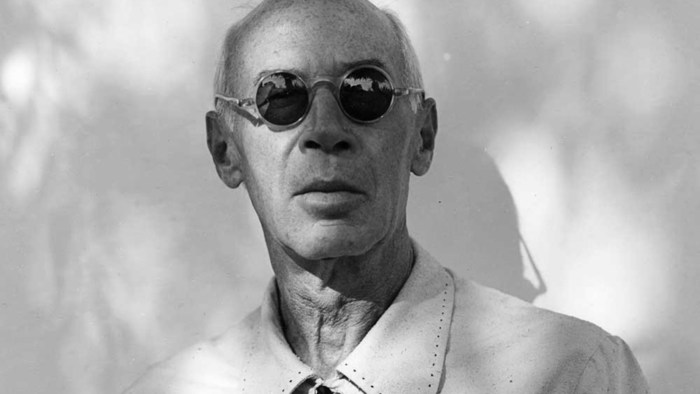

Throughout his long life, Henry Miller (1891-1980) wrote a handful of good books, among them The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945), in which the prodigal son and narrator returns from self-imposed exile in France to tour his native United States by automobile, and Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch (1956), a back-to-the-land meditation that prefigured some of the next decade’s communitarian experiments. Both, along with one or two other of Miller’s books, will endure in the literature of American social criticism as fine examples of the polemicist’s art.

Miller, of course, is remembered for none of these books, but for a tide of pornographic and near-pornographic novels published both pseudonymously and under his own name: Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, Sexus, Quiet Days in Clichy, and nearly a hundred others. Of these books. Miller boasted, “The difference between me and other writers is that they struggle to get down what they’ve got up here in the head. I struggle to get what’s below, in the solar plexus, in the nether regions.” Smuggled into the United States in sub-rosa French editions, these “dirty books” titillated generations of American adolescents, who skipped over Miller’s mawkish attempts at artistry to get at the naughty paragraphs deep within.

Read today, with the constant commodification of sexual relations in the intervening decades, the great bulk of Miller’s books seem tame, awkward, self-conscious curios, the sort of stuff that collectors rush to gather but readers, in the main, pass over. In that light, it seems curious that two major American publishing houses should have found need to commission major biographies of Miller for publication in the centenary year of his birth. Yet here they are: two far different lives, both celebratory, both incomplete.

Mary Dearborn’s The Happiest Man Alive—its title taken from a characteristic Miller boast, “I have no money, no resources, no hopes; I am The Happiest Man Alive“—is, in the way of academic biographies these days, marked by pop-psych/postmodern self-satisfaction. The author seems content to write off Miller’s philandering, violent temper, anti-Semitism, fascist leanings, and other dark aspects as manifestations of the fin-de-siècle America into which he was born, and nothing more. A historian, Dearborn does not often consider Miller as a writer; for her, he is more a laboratory specimen on a Lost Generation mounting board. Despite its varnish of sometimes interesting feminist and psychoanalytical theories, Dearborn’s treatment remains stubbornly superficial.

Dearborn is especially pressed to explain Miller’s most famous relationship, that with his second wife, June Smith, a dime-a-dancer who passed off Miller’s writing as her own to secure the patronage of a wealthy admirer. With the proceeds, the two went to Paris, eventually entering into a triad with Anais Nin, whose diaries give a more interesting picture of Miller than do either of his subsequent biographers. (The 1989 film Henry and June recapitulates their three-way affair; for its tawdry realism, the film earned the industry’s first NR rating, meaning something like “X with a plot.”) For Dearborn, June is little more than a grifter whose sole mission is to derail Miller’s career by systematically undoing him emotionally—a strange take, it would seem, for a feminist critic—rather than an equal player in a Bohemian funhouse.

June earns more sympathetic treatment in Robert Ferguson’s Henry Miller: A Life; in his eyes she becomes at least something more than a destructive siren. Ferguson is at pains to rationalize and defend Miller and his familiars at every turn. Like so many exponents of every counterculture known to history. Miller, for instance, was gullible in the extreme when it came to faddish religions, embracing Vedanta, theosophy, Scientology, and other occult doctrines indiscriminately; for Ferguson, “his spontaneous attraction to frauds” becomes not a mark of inconstant intellect but “an odd and even touching index of his credulity.” Ferguson’s breezy style makes his book a better bet for the casual reader than Dearborn’s drier academic approach, but on the whole it is a long exercise in People magazine journalism.

There are any number of nasty diseases afoot to remind us of the consequences of the love-without-care platitudes Henry Miller committed to print and history. Anyone who still adheres to these ideas clearly has not been keeping up with the newspapers. Miller’s real contribution, apart from his few enduring books, remains his willingness to champion free speech, his refusal to bow to censors of whatever stripe. He inspired others of his time in this cause—the critic Lionel Trilling, for example, who was moved to remark of Miller’s novel Black Spring (1963), “This is a book which I will be glad to defend but not to praise.” Miller’s battle of two decades to publish his work freely in the United States, which both biographers adequately recount, has since allowed once-controversial writers like Erica Jong and Philip Roth their place on the shelves without the specter of being “banned in Boston.”

But Henry Miller’s time is long past, and these twin lives are too little, too late.

[The Happiest Man Alive, by Mary V. Dearborn (New York: Simon & Schuster) 368 pp., $24.95]

[Henry Miller: A Life by Robert Ferguson (New York: W.W. Norton) 397 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply