“How shameless and how greedy all these people are!”

—Fyodor Dostoevsky

Once there were three finance firms and then there were none. One was a Ponzi scheme, one a tax fraud, and the last was sold to American Express for $380 million. One CEO is broke and in jail; one is a wealthy fugitive from U.S. justice, living in Switzerland on a Spanish passport; and the third pocketed $23 million of buyout money. If Theodore Dreiser had written The Three Little Pigs, he couldn’t have exposed the ravenous greed of today’s financial marketplace any better than these contemporary tales of business morality and the lack of it.

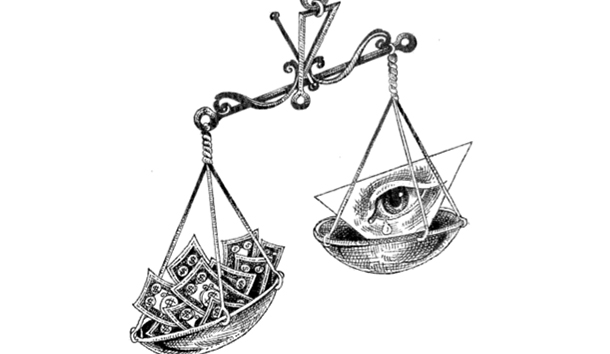

Fostered alike by the capital needs of big-deficit government and the abuse of deregulation, financial fraud is rampant. Record-setting insider trading, tax evasion, bank failure, and investor bilking were commonplace in 1986. “Nobody steals Fred C. Dobbs’ gold!” snarled Bogart in the film version of Traven’s Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but the times have changed. Finance is a global high-tech operation, and the world is living on high-speed credit—theft is a cash flow problem that hurts only taxpayers, small investors, and out-of-work employees.

In the newly leveraged America, top executives have more money than God. What is said of Marc Rich & Co. is true for J. David Banking and Lehman—”There was so much money that everybody in the firm lost touch with reality. . . . They were so cocky that they thought their next deal would be for the nails that put Christ on the cross.” But having more money than God means two things: To be rich as Croesus is also to mistake mammon for God. The proverbial saw is literally double-edged—to believe in money more than God is to have no god at all. Finance, meaning the banking that concludes a transaction, comes from the French for end, and when finance becomes an end in itself the moral consequences are devastating.

Starting with less than nothing in the basement of a Mexican restaurant in Lajolla, Jerry Dominelli raised $200 million from investors in live years. Some of his clients got out of J. David with fat profits, but those who didn’t lost $100 million—including the $10 million claimed by the IRS. It is doubtful that anyone believed Dominelli’s phony track record of investment success in trading foreign currency in the unregulated interbank market. His customers were never told what and when they had traded, never received confirmations in their own name, never received audited statements, and were told only that their account was up X percent in a month. But the first investors were making 40 or 50 percent a year—because (as is the nature of all schemes called after the Boston swindler Charles Ponzi) they were being paid with the deposits of later recruits to the scam!

San Diego financial columnist Don Bauder writes: “For sophisticated investors, it was a battle between common sense and greed, and the latter won.” For the less sophisticated it was a disaster built on the greater-fool theory—smart people went in and got out quickly, hoping to leave the losses to the next investor. The suckers included comedian Joey Bishop, San Diego Mayor Roger Hedgeeock (later convicted of conspiring to funnel $350 thousand from Dominelli sources to his campaign fund), and the Preacher’s Aid Society of Decatur, Illinois, which manages pensions for 800 retired Methodist ministers and “keeps a modest amount of money on the side to take an occasional run at a highflier.” Having “checked out the Dominelli bank thoroughly before depositing any money,” the executive secretary sent $681,759.42 to J. David. Cupidity, not stupidity, was Dominelli’s chief source of success.

The greed machine requires the fantasy of a “pathological liar,” as Dominelli’s house lawyer styled him, and a true believer with the right connections, like socialite divorcee Nancy Hoover. Because the liar and the believer are not smart enough to cook up the seam, a villain is also needed to complete the cast. Deep Throat told Woodward and Bernstein to “follow the money,” and in the case of J. David it leads to Mark Yarry, who did not flee to Montserrat with Dominelli and Hoover but escaped quietly to France with personal control of some $3 million of J. David funds.

Bauder doesn’t know why Yarry wasn’t prosecuted, but he does suggest that Yarry’s 1981 book, The Fastest Game in Town: Commodities, deliberately puffed Dominelli. Yarry also contributed the plan for currency trading through a Caribbean shell bank. The odd trio then bought a team of money-finders who paid as much as 20 percent of what they brought in: a prestigious law firm, Rogers & Wells, cost $500 thousand a year more; for accountants, J. David used Laventhol & Horwath (who have yet to empty their deep pockets). Finally, a PR man was taken on for a six-figure fee so he can later tell a jury: “I don’t rule out the possibility that . . . but I cannot answer the question in terms of specifics, because I do not recall. I don’t think—I mean, it is altogether possible that I would have said . . . but I can’t answer the question any more specifically than that because I do not recall. And I just barely recall the possibility that there may have been a luncheon at the Hilton involving Roger Hedgeeock and myself.”

J. David bought the mayor, but left state and Federal regulators to confuse themselves. Since the firm was not licensed to sell securities in California, its lawyers convinced the state that it was selling commodities. “We were unable to determine that [J. David] was doing business in the state,” reported its own local bank, San Diego First National, with a blink. At the Federal level, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission was snookered because the accountants found that “due to a Montserrat statute relevant to bank confidentiality, the records of J. David banking could not be examined.” But a Rogers & Wells attorney could take a peek at the books and assure the accountants that all was in order. This “scope limitation” allowed Laventhol & Horwath to issue a clean bill of health. Then J. David wrote to the accounting firm that it approved of the altered procedure!

Both the SEC and the FBI looked J. David over and then looked away. Bauder writes: “The fact that J. David succeeded as long as it did is a powerful argument for strong government regulation. . . . The fact that J. David completely eluded federal and state regulators is an equally powerful argument that government regulation is a waste of time and money.” More money than God made Dominelli the epitome of self-deregulation, but it was the same money that ultimately defeated him.

The evidence suggests “that the success of the scheme in fact stunned Dominelli. As the money poured in, even he might have understood that the more that came in, the deeper he would eventually be buried.” J. David lost money in every foreign currency account people had knowledge of—at Bache, at Merrill Lynch, at Drexel— but still the money poured in. Captain Money and his Golden Girlfriend tried to spend their way out of the problem by acquiring three jets, dozens of $100,000 foreign sports cars, race horses worth $650,000, a $50 thousand Bulgari emerald, $1 million worth of ski condos in Utah, a Rancho Santa Fe estate and land worth $3.2 million, $5 million worth of elegant townhouses, a posh Italian restaurant in Del Mar, a Porsche racing team, and a stake in a gold mine. Ironically, the more they spent on conspicuous consumption, the more investor money rolled in. The weight of money and more money brought down the house of J. David because more money than God is a self-fulfilling prophecy with a bankrupt ending.

Marc Rich’s billions were no less greedy than Dominelli’s millions, and his daisy-chain operation—while not a Ponzi—no less a crime. As a former head of trading at Philipp Brothers remarked, “The world changed in 1973. . . . Everybody got greedy.” The Arab-Israeli war meant OPEC, and OPEC meant spot-oil trading on a scale never before realized, and “it was the oil money that made everybody crazy.” By 1980 the Rich empire was making $367 million a year. By 1984 he was making enough money to view the $50,000 a day fine levied on his companies as a nuisance fee aiding his successful delaying tactics in the largest individual tax evasion case ever. Rich settled with the government for $210 million, while safe from personal prosecution in Zug. But the arrogance that comes with more money than God soon had him boasting that he could trade his way out of the loss in less than a year.

Copetas’ badly written book outlines Rich’s crime but not its subtleties. During the oil crisis. Rich would sell OPEC oil to a domestic company for less than the $35 market price. In return, the company would sell him controlled $6/barrel “old” domestic crude. Rich would then whip around title to the old oil using his own domestic and Panamanian companies until it lost its identity and emerged at the end of the chain as new oil worth the market price. But what Rich made was more than the difference between six and 35 dollars; profited at every point in the chain. “Marc Rich, say those who know him,” Copetas writes, “would make a pact with the devil if he could become a cartel”—which in effect he did.

Rich started trading for Philipp Brothers in the 1950’s, and as the firm’s man in Castro’s Havana, he learned the exploitation needed to conduct business in the Third World. “Rich more than any other Philipp’s trader stretched the fine line between graft and gift.” He used the same techniques later when he was trading Iranian chrome, developing intimate contacts with high Persian ministers and members of the Shah’s family. The same techniques also worked with the Marcos government in the Philippines, and equally with Marxist rebels in Angola. The Russians, also Rich clients, defended him against U.S. persecution with an editorial in Izvestia. The Iranian connections helped Rich buy crude at a $5 premium over spot prices in 1973. He was stockpiling in advance of the first embargo, but Philipp’s forced him to abandon the position. Frustrated, Rich quit, taking the best of the firm’s younger traders with him, and went out and bought an oil tanker.

Oil prices soared, but somehow Rich was able to buy $20 OPEC oil for $15 and sell it at spot for $24. The $125,000 a Rich trader claims to have deposited regularly into the coded Swiss account of an Iranian oil minister must have helped. By 1980 Rich was selling ARCO 40,000 barrels a day at an $8 premium over the official Nigerian price (which he didn’t pay) of $24—and this cost ARCO less than the spot price for 27 million barrels. Rich even sold Nigerian oil to South Africa, and when his suppliers found out by following his tanker, it cost “one million chocolates to get the contract back.” The payola—only a down payment on a $12 billion deal—went to a transport minister related to former Nigerian President Shegari, “whose regime personified corruption in the Third World.”

Even when the Shah died. Rich kept right on making money in Iran; characteristically his traders immediately took Khomeini’s oil ministers out to lunch. Rich knew that in the 1930’s Texaco had made money by selling oil to Franco and got away with it. In the 1980’s he would do the same by buying from the enemy instead—a crime during the Carter Administration. During the hostage crisis. Rich & Co. bought millions of barrels of Iranian crude at half the $40 spot price and paid for it with what the Ayatollah wanted most—arms!

Rich was making more money than God before he joined other daisychainers. It is a measure of his own arrogance, and of the way greed worked to bring about his downfall, that he decided to make even more by cheating the U.S. government. But Rich could not resist. He made money selling the cheap oil he got from Nigeria in the U.S.; he made money on the cheap oil he illegally bought from Khomeini and sold at home; he made money by getting domestic old oil at a further discount in return; he created tax advantages for his domestic subsidiaries by selling this oil at a loss to his Panamanian companies; he created tax-free profits for those firms by selling the old oil at a gain multiplied by the difference between old and new oil; and he could even pump the new old oil back into the chain if the spot price went to a premium.

It took the Department of Energy eight years to find out what was happening—bureaucratic stupidity can do the work of chocolates. But Federal accountants finally figured out that more than 400 million barrels of old oil had disappeared, based on a comparison of old oil bought at the well and the amount arriving at the refineries. The government response was typically absurd—DOE set a 20(2a-barrel profit limit on old oil! At least Rich’s prosecution brought in $210 million.

As Ken Auletta explains, greed for more money than God turned the heads of the respectable investment bankers of the house of Lehman. (This is a book that can’t be put down—at a recent meeting with an SEC official, the first question I was asked as an investment advisor was whether I had read it.) One Lehman partner told Auletta: “We were making money. All the people cared about was their money. Greed.” Another remarked that “Lehman was held together strictly by money, blood money.”

But despite the money pouring into the firm, the Lehman partners “did not think of themselves as wealthy, despite annual earnings ranging from $500,000 to more than $2 million, in addition to owning millions of dollars in Lehman stock.” And when Peter Cohen, head of the Shearson side of Shearson/AMEX, pushed his bid for Lehman—boasting that he made “$1.2 million last year, and seventeen people at Shearson made more than me!”—the Lehman partners “rolled their eyes,” because as one said, “after taxes we all made more than him.” Once you get more money than God you need more money than God. The fall of the house of Lehman came about when its partners discovered they didn’t have enough.

By 1967, Lehman—founded in 1850 by German-Jewish immigrant brothers who started trading cotton in Montgomery, Alabama—was responsible for $3.5 billion in underwriting and was among the top four Wall Street investment banks. Auletta’s narrative begins in 1969 with the death of Bobbie Lehman, the last of the name to run the partnership and the ruler whose twofold legacy began the firm’s demise. Bobbie groomed no successor and established no system of consensual governance. Individual partners knew how to manage individual clients but not how to manage themselves collectively.

In 1973 they chose Pete Peterson, who had come to the firm only two months earlier when President Nixon deposed him as his Commerce Secretary, as CEO—on the basis of his administrative experience. The second half of Bobbie’s legacy consisted of Lew Glucksman, hired away from A.G. Becker in 1962 with his own commercial-paper team to establish trading at Lehman. Bankers initiate loans; traders sell and buy the collateral—Bobbie wanted to make money on both sides of the financing process. The two-fold approach seemed the only way to deal with dramatic changes on Wall Street. Lehman’s story is one of the tragic conflict of Glucksman and Peterson, each trying in his own way to deal with the other, and with the larger forces at work in the leveraging of America.

Deregulation increased competition on Wall Street. Investment banking quickly became less a matter of social and political connections and more a matter of price. Giant corporations could now afford to hire their own money managers, who sought to maximize profit on a day-to-day basis rather than worry about the firm’s long-term profitability. Trading was in the ascent and by 1983 accounted for more than two-thirds of Lehman profit. Risk arbitrage and new financial instruments further emphasized trading. Investment banks needed more capital—Lehman could trade $15 billion of government financing in a single day.

The increased need for capital and markets forced the creation of financial super stores—Prudential plus Bache, Dean Witter plus Sears. The takeover of Lehman has been called “McDonald’s taking over the ’21′”—but the real name of the hamburger joint was Hayden, Stone, Shearson, Hamill, Lamson, Faulkner, Dawkins, Sullivan, Loeb, Rhodes, Hornblower, AMEX. Merger mania drove up the prices of financial firms along with the rising price of financial assets, and because the firms were worth more, more partners were willing to sell them, particularly Lehman partners, who were required at age 60 to sell their shares back to Lehman for book value only (ca. $1,250).

The polarization of bankers and traders at Lehman was no different from that of cowmen and farmers in the Old West. Bankers held 67 percent of the shares and 51 of the 79 partner titles, but the traders were bringing in more than twice the profits. Glucksman proposed a radical redistribution of the shares, and Peterson turned him down, setting the stage for a power struggle. The outcome of that struggle was first determined by money and then by greed for even more. Money in the form of gushing profits helped make Glucksman co-CEO in 1983. Shortly thereafter he engineered the coup which forced Peterson out.

But in the months before his golden handshake took effect, Peterson forced Glucksman not out of his job but out of his company. The ebb and flow of this struggle is portrayed with genius in Auletta’s account, and the same strength powers his conclusion: “Greed was the word that hovered over the troubled partnership. To their faces Glucksman accused the senior bankers of greed for money. Behind his back, senior bankers accused Glucksman of greed for power. Traders said the bankers were greedy because they were privately angling to sell the firm. Bankers said the traders were greedy to steal their shares and to take such fat bonuses.”

Tensions at Lehman centered on Glucksman’s suspicion that Peterson wanted to sell the firm before he turned 60 in order to sell his thousands of shares at a profit well over book value and at the expense of partners with far fewer shares. “There is no question he was interested in selling the business,” says Glucksman, “he was obsessed with money.” Neither man, however, was to determine Lehman’s fate. Not even the Lady Macbeth of the conflict—Peterson’s wife, Joan Ganz Cooney, founder of Children’s Television Workshop—could decide the issue, though she seems to know more about the games big people play than her recent libertarian Smith College commencement address on economic equality would suggest: “She knew that Glucksman was violently opposed to the idea of selling the firm, while it was Pete’s private hope to sell Lehman before he reached sixty.” “Pete certainly hoped it would sell in that period,” she told Auletta, “and we’d have no money worries. . . . Our sole interest was in getting as much money as we could.” At the time of these remarks, her husband was earning the equivalent of $5 million a year after taxes.

But Peterson’s greed and Glucksman’s passion were equally ineffective in the end. The market itself had its revenge on the house of Lehman. Late in 1983, profits dried up as trading losses escalated, and Lehman was down $30 million by the end of March 1984 and more than that amount in the following month alone. “Glucksman was shorn of his armour. No longer was he a guaranteed money maker. A fickle market had denuded a troubled partnership.” Peterson walked away with a package worth $23 million. “Maybe it’s a little too rich,” he remarked to the AMEX people.

[Greed and Glory on Wall Street: The Fall of the House of Lehman, by Ken Auletta; New York: Random House]

[Captain Money and the Golden Girl: The J. David Affair, by Donald C. Bander (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich) $15.95]

[Metal Men: Marc Rich and the 10-Billion-Dollar Scam, by A. Craig Copetas (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons) $17.95]

Leave a Reply