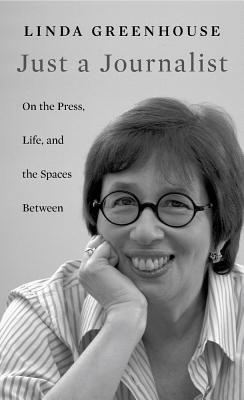

Let’s give credit where it’s due. Linda Greenhouse, retired Supreme Court correspondent for the New York Times, is a brilliantly qualified journalist: hard-working, creative, dedicated to the needs of her profession as she understands them.

Which seems really to be the problem here; a problem large and grave, requiring critical analysis. Greenhouse’s very personal sense of journalism’s necessities strikes me—her contemporary in the profession—as well-meant but grotesquely misguided. She wants journalists to turn themselves into teachers and preachers. I say, ixnay, lady.

I will tell in a moment why I say so. Some preliminary stage-dressing is wanted in the meantime.

First, the nature of the present enterprise—a short account of the author’s life in journalism mingled with observations meant for an audience at Harvard’s William E. Massey Sr. Lectures in American Studies. In the book compiled from her discourses, and expanded to account for the Trump phenomenon, “I explore,” the author says, “the relationship between journalist and citizen and question whether prevailing norms fix too rigid a boundary between the two roles.”

Yes (she concludes), they really do. Linda Greenhouse doesn’t believe in “objective” journalism—just-the-facts-ma’am journalism, as Sgt. Joe Friday of Dragnet might have understood it. Well, yes, facts—but not in the way journalists have long understood the obligation accurately and honestly to tell readers what just happened.

Greenhouse quotes, with rhetorically arched eyebrow, the dictum of Arthur Hays Sulzberger, publisher of the New York Times from 1935 to 1961. Sulzberger capsulized his philosophy as “We tell the public which way the cat is jumping. The public will take care of the cat.” The founding publisher of the paper for which I long labored, the Dallas Morning News, delivered corresponding counsel to his staff: “Acknowledge the right of people to get from the newspaper both sides of every important question.”

Such was the canonical wisdom of the day. People could make up their own minds. No need to ply them with reportorial opinion, notwithstanding the earlier disposition of newspapers to lay about with cudgels and acrimonious adjectives. The maturing of the profession, and the spread of literacy, made objectivity, of a variable sort, a reachable and praiseworthy goal for the entrenchment of democracy.

Yet, to Greenhouse’s mind, old Sulzberger spoke for the past.

[S]urely we now know, in what has come to be called the post-truth age, that simply reporting which way the cat is jumping falls short if the goal of journalism is to empower readers to sort through the noise and come to their own informed conclusions. For that, they need context: not just what happened a minute ago, but what led up to that minute, why it happened, and what might come next.

Thus “reader empowerment” becomes journalism’s “highest goal.” Not just the facts, ma’am, but the right facts—selected reportorially to indicate consequences, responsibility, stakes, guilt, innocence, heroes, villains. According to whose suppositions? Why, the suppositions of the architects of “context”—writers, reporters, editors, researchers. Which is fine with Ms. Greenhouse, looking out on the larger world from the smaller one where dwell the big cheeses who know exactly what needs knowing—those who care what happens to the cat beyond the arc of his jump.

“If one side is correct and the other mistaken” or “morally insupportable,” she explains, “the resulting false balance of false equivalence” that comes from balanced treatment of both sides “can seriously disserve the reader—and society as well.”

There is a beguiling, as well as infuriating, innocence to the proposition that journalists should be in charge of our minds and decision-making, telling us which side is “correct,” which incorrect—not to mention morally challenged. Who elected the practitioners of daily journalism to sit at the head of the national classroom, writing precepts on the blackboard for class memorization? True, no one has to read the New York Times, far less subscribe to it (as I myself have done for decades), but the point lies elsewhere. As is true, actually, of numerous points Ms. Greenhouse determinedly skirts. Here are the main ones, as I see them.

First, there is the ideological lopsidedness of the media: the outraged liberalism of, say, Linda Greenhouse’s Times.

The liberal (“progressive,” if you prefer) takeover of the Times was never a foregone conclusion, despite the paper’s longtime nonconservative, New York bent. The Times, I judge, changed with the times: the cultural splinterings and sunderings, the political wars, the acrimony, the hatreds that emerged in the 1960’s. New generations—starting with Linda Greenhouse’s—came aboard, with differing views of obligation.

Greenhouse long ago came out of the closet as a supporter of abortion and Planned Parenthood. “[I]n the spring of 1989, I had joined some college classmates and a half million other people in a march for reproductive rights on the National Mall.” She takes pride in her monthly contributions to Planned Parenthood—which do not necessarily impeach, but certainly do cast into deep shadow, her right to write about the vexed topic of the Supreme Court’s abortion jurisprudence. Do you trust her ability, as a partisan of the pro-abortionists, to tell you the whole truth about a legal case involving abortion? She seems to think we should. We might say in reply: Why? On what grounds?

Second, there are the malign consequences of “reader empowerment,” à la Linda Greenhouse.

We notice at once the inability of nonliberals, save randomly, to receive equivalent and fair attention from the media. Or to escape regular reprobation for their supposed ignorance, bigotry, racism, sexism, you name it—all the hallmarks of conservatism and conservative thought, as many a liberal journalist appraises the matter. This is what we tend to call “media bias,” and bias it is—a snippy, snobbish desire to define what kind of care, and with what consequences, the public, in rejection of sexism, homophobia, etc., wishes on Mr. Sulzberger’s cat.

No longer, we have observed, do the media shrink from the castigation—in news columns, formerly meant for telling which way the cat jumps—of conservatives, or those thought sympathetic to conservative ideas. Consider the Times’s December 31, 2017, front-page appraisal of the Trump presidency (written by Peter Baker, one of Barack Obama’s biographers):

The presidency has served as a vehicle for Mr. Trump to construct and promote his own narrative, one with crackling verve but riddled with inaccuracies, distortions and outright lies, according to fact checkers. Rather than a force for unity or a calming voice in turbulent times, the presidency now is another weapon in a permanent campaign of divisiveness.

Deployment of the word “lies” in discussions of Trump—as if “inaccuracies” or “exaggerations” fell short of the mark—is a provocation of the sort to which the media have long since accustomed readers and viewers. Earlier this year it became fashionable to declare the President nuts, or nearly so; a potential straitjacket candidate.

Trump-loathing isn’t exactly a localized affliction, but in older times the Times would have kept such ferocious opinions on the editorial page, where they properly belong, representing the viewpoint of the paper rather than of one particular reporter and complicit editors. An important newspaper would not have made itself an official vehicle for the mortification of the unenlightened.

That the Times consented to become such a vehicle shows the lengths to which the “reader empowerment” obsession is corrupting, rather than furthering, free and open discourse. Truth is what the likes of Peter Baker and his ideological confrères conceive and declare it to be. Trump is a liar and a demagogue. Say no more.

Which is not the outcome our constitutional arrangements presuppose. Debate and discussion, not public hectoring, are central to the enterprise of figuring out public policy. Nobody has to acknowledge Trump as other than the weirdest president we may ever have had. The task for journalists, surely, is to figure out not just when he’s full of it but when he’s behaving with some semblance of normality.

Failure to do so not only undermines civilized discourse but splits away elements of the public from those supposedly informing them. When the media become, in numerous eyes, The Enemy, to be hated and resisted at all costs, the First Amendment to the Constitution takes it on the chin.

Linda Greenhouse argues for examining our problems “in context.” Oh yes? Whose context: the lived, experienced kind or the theoretical kind associated with university seminars and urban cocktail parties, the likeminded massaging of each other’s nervous tics and sensibilities? And who, in such an environment, is listening? The staggering condescension of We’re-Here-to-Empower-You-ism helps explain the rancid relationship readers have fallen into with their news providers.

As for the modern canard that declares objective journalism unnecessary or improbable, I can only say, from lived experience, what a pile of garbage. Objectivity isn’t easy when passions run high, as now. But, as a reporter, you go after it because you’re supposed to—out of respect for professional standards and, equally, for your audience, and its intellectual and emotional capabilities. So the game was played, anyway, in more fruitful journalistic times than these.

In my own reportorial days, I actually considered objectivity fun—a challenge; a kind of sport. The stronger my personal objections to a viewpoint I was writing about, the harder I worked to squeeze from the written story every drop of personal partiality. Whenever I succeeded, transports of professional delight enveloped me.

Long time ago, you say. Indeed. The argument we carry on today concerning bias in the media has a fine set of white whiskers. It was hot stuff in the 1970’s and 80’s, when, in the wake of Watergate, the media began to practice “advocacy journalism”—a forerunner of “reader empowerment,” and just about as fraudulent. The incantation I deployed in those days concerning old-fashioned objective journalism went, “We’re your eyes and your ears. We’re not your brains.”

I thought that formula on target then; I think it on target still. No institution has endowed the media with power over a society whose needs daily grow more complex. The preachments of today’s news-gatherers grate against the aims of the First Amendment—namely, the encouragement of free, open, and, most of all, civilized discourse, for the sake of practical problem-solving.

We know the theory: I thumb my nose at “reader empowerment”; the empowerment folk thumb back. We have at each other until we decide how to live together on some logical basis or another. So constitutional democracy works—when given rein by its supposed supporters.

[Just a Journalist: On the Press, Life, and the Spaces Between, by Linda Greenhouse (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press) 192 pp., $22.95]

Leave a Reply