Moving by fits and starts, this biography of the Southern novelist and wife of Allen Tate lacks focus and—ultimately—purpose. Veronica Makowsky’s is a dull account of an inherently interesting subject. This relatively small book is essentially a failure, rendering, as it does, a diminished, fragmented, and elusive portrait of Caroline Gordon.

The book does include some entertaining anecdotes, but these generally involve a funny comment made by the Tates’ young daughter Nancy that is transcribed verbatim. Unfortunately, when the humor turns on action rather than on words, Ms. Makowsky’s ineptness becomes painfully visible as she takes rich material, such as Gordon’s initial encounter with William Faulkner, and renders it limp, pallid, and anticlimactic.

Makowsky deals too much with the work and not enough with the life. One feels that she was perhaps trying to compensate for a dearth of information, or maybe she felt preempted by Ann Waldron’s 1987 biography, Close Connections: Caroline Gordon and the Southern Renaissance (which, while flawed, is much the better of the two books). When not putting the reader to sleep with plot summaries of Miss Gordon’s work, Ms. Makowsky is busy dousing him with buckets of Freudian interpretations. Recounting Gordon’s explanation of how she first learned to read—a spontaneous experience involving “Beauty and the Beast”—Makowsky helpfully explains: “Although at the end of the story Beauty turns the Beast into a handsome prince with her kiss, much of the tale’s suspense concerns the fate of Beauty’s father. . . . Little Caroline, who worshipped her father, may well have identified with Beauty and longed for a similar opportunity to prove her love.”

Worse than her tendency to make much put of little, however, is Makowsky’s propensity to make something out of nothing. For example, her comment concerning the Tates’ argument with their live-in guest, Hart Crane, is totally unwarranted. Because, according to Crane, Gordon had accused him of spreading himself and his “possessions all over the house, invading every corner,” Makowsky conjectures that: “Caroline may have been demonstrating her territorial rights over Allen to the homosexual Crane since her words and actions concern the warding off of an invader.” Waldron’s more credible account is that Gordon was trying to conserve time and space for her writing, not for her husband. On other occasions, when the need for authorial comment is apparent, Makowsky is restrained, and even silent. Both biographies address the subject of Caroline Gordon’s rumored single abortion (a possibility, according to Makowsky; a fact, according to Waldron), but, curiously, neither biographer is able or willing to comment on what, if true, must have been the source of subsequent distress, in light of Gordon’s later conversion to Catholicism.

According to Waldron and Makowsky, Caroline Gordon had two passions: literature and Allen Tate. Yet while both of her biographies manage to convey a sense of their subject’s writing, they fail to elucidate the depth and degree of her love for Allen Tate, or even to render the essential nature of that relationship, despite their close attention to Tate’s infidelities and Gordon’s steadfast patience, as well as their two marriages and several separations.

Ultimately, both Makowsky and Waldron lack real sympathy with their subject. Tellingly, both establish an implied contrast between Miss Gordon’s “Southern” qualities (which they disparage) and her “feminist” ones (which they approve). They offer an oversimplified explanation of Miss Gordon’s gregarious hospitality and untiring efforts to help other writers as “compensations” for difficulties within her marriage. While this explanation may be true in part, surely her generosity of spirit was also inherent in her personality and was nurtured during her early years spent among the extended family that congregated at her grandmother’s farm.

What Veronica Makowsky does offer the reader is a clear appreciation of Gordon’s classical education and its importance to her work, and she provides also an appreciative evaluation of the artist’s talents as a teacher of writing. And, if we exempt the incomparable Aleck Maury, Sportsman, which is full of wit and humor, her following observation on Gordon’s fiction is astute:

Her works are often beautiful examples of technical mastery, but the thoughts, the feelings, the wit, and the humor that enlivened her letters and her conversations are absent from her characters and her authorial voice. In some ways the very seriousness with which she regarded the art of fiction barred her from the serendipitous, impulsive plunges into the human heart that often make for great fiction.

There are other instances where Makowsky is on target. Yet, for the reader, the harvest is taxing, the yield hardly worth the effort.

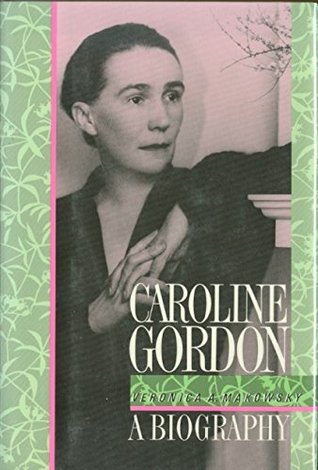

[Caroline Gordon: A Biography, by Veronica A. Makowsky (New York: Oxford University Press) 221 pp., $21.95]

Leave a Reply