This book is mistitled, in the sense that Richard Nixon is the least interesting of the multivarious subjects covered herein. The author, of course, is not to blame for that fact; and perhaps it was modesty that kept him from perceiving where the strengths of his collection really lie.

These essays differ in depth and in quality as well as in their subject matter, but the best of them—”When We With Sappho,” “The Betrayal of Ernest Hemingway” (published last year in Chronicles), “The Imaginary Atlas,” and “To the Manner Born”—show McNamee to be a natural handler of the essay form. He has the born essayist’s requisite breadth of learning, his facility for the long and deceptively easy-seeming reach, and—where the subject under discussion is neither RMN nor Ronald Reagan—his relaxed tone conveyed by a distinctive personal voice. Though as a writer Gregory McNamee is politically speaking very much engagé, he is at his best artistically when dealing with literary topics. Of the many performances included in this collection, “When We With Sappho” (about the poet, essayist, painter, critic, and classicist Kenneth Rexroth) is the most learned; “Buried Under the Volcano” (concerning the novelist Malcom Lowry) and “The Betrayal of Ernest Hemingway” (on the subject of Hemingway’s heirs and assigns, who took it upon themselves to publish posthumously the author’s unfinished third-rate manuscripts) are the most sensitive and compassionate; while “The Imaginary Atlas” is a textbook example of the essayistic art of digression, progression, modulation, and final resolution. It is also perhaps the work in which the author most completely realizes his natural voice—its pitch, its tone, its mood:

Southern Utah is scorchingly hot in the summertime; good weather for rattlesnakes, poor weather for traveling in an automobile without air conditioning . . . I stopped in Mount Carmel, a lovely green town, for a cold beer with which to combat the elements. I found one, too, for even alcohol-shy Mount Carmel lies within the oikoumene, the habitable world of the Homeric poems, distinguished by the things of civilization. Much as some might suspect the contrary, the state of Utah—or most of it, at any rate—is not Philoktetes’s cave.

From this introductory paragraph—so varied in mood, diction, and frame of reference—”The Imaginary Atlas” proceeds to its pantheistic conclusion via such intermediary subjects as Utah beer signs. King Roger of Sicily’s map of Idrisi, humanly conceived borders and “the manifold divisions of the world in space and time,” Joseph Conrad and “places of darkness,” fabulous geography in Western history, fractal geometry, and Gaian ecology. About mid-passage, the following sentence appears: “We would want to know the ancient names of all places, for the past is a land we may inhabit whenever we wish.”

That sentence is significant, for its burden is central to McNamee’s understanding of the nature both of time and of human culture. “A current notion in contemporary physics, the epic poetry of our day,” McNamee writes in “When We With Sappho,” “is that time is granular, meaning that somehow time has a physical nature and can therefore be as easily bent and molded as a beam of light or an electro-magnetic pulse. . . . The so-called primitive languages have recognized it for millennia, but the Euroamerican mind is just beginning to accept as commonplace that time is not neatly ordered, that it is nonlinear, that it is relative to the viewpoint of the observer.” The notion that the past exists in both present and future was a central tenet of 20th-century Modernism, and the point of this is not lost on McNamee, who grasps as firmly as did T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Faulkner, and Kenneth Rexroth the fact that “a civilization must have continuity and memory if it is to endure, that modernity should not be obliteration but extension.”

Though in strictly political terms McNamee may be a Man of the Left, culturally speaking he belongs in that category of anomalous men who—like his friend and sometime collaborator, the late Edward Abbey—resist the traditional outworn taxonomy of Left and Right. In fact, in the present volume, the essay “Scarlet ‘A’ on a Field of Black”—whose subject is Abbey’s politics and art, which Abbey considered, as McNamee does, to be one and the same thing—makes patently clear how much civilized people of the “Left” and the “Right” share both a common complaint and a common enemy in the post-Modern world. When Gregory McNamee writes of “the disastrous times which we inhabit” and refers to what he calls “the present barbarism,” men and women for whom that disaster and that barbarism are not—as they are for McNamee—almost totally signified by “The Age of Reagan” nevertheless know exactly what the author is talking about.

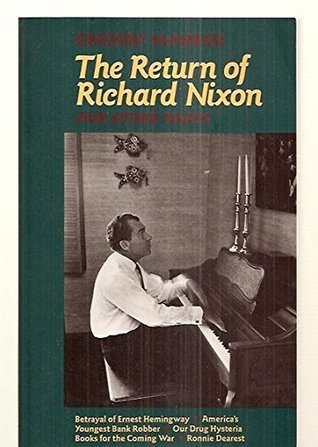

[The Return of Richard Nixon and Other Essays, by Gregory McNamee (Tucson and New York: Harbinger House) 213 pp., $9.95]

Leave a Reply