Anticipating the latest Flashman novel is always a delight, and then there are the reviews to look forward to. The best of these are humorless, priggish, and hortatory, and read as if they had been composed by the writer with his left hand, while he was holding his nose with the right one. For bookmongers of this sort, the fictional Sir Harry Flashman, VC—coward, cad, ravisher of willing women, and genial oppressor of all people of color—is so complete a representation of the White Heterosexual Male Monster in action as to have attained reality and become one of the documented bugaboos of the unredeemed historical past. Their response suggests that, in Sir Harry, George MacDonald Fraser has created a stereotypical anti-hero; paradoxically, the opposite is really true. Fraser’s genius is expressed in his ability to compound two stereotypes—that of the Victorian hero and of the Marxian exploiter and butcher—with such skill and imagination that the result is a fictional character of parts, alive and at large in a world of multiple dimensions. Let those who have ears, hear; those who have eyes, see!

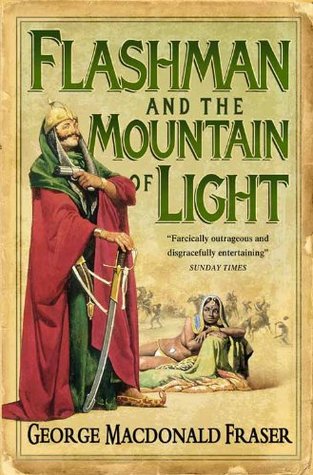

Flashman and the Mountain of Light is the ninth volume developed from a series of manuscript packets, wrapped in oilskins and discovered more than twenty years ago in a saleroom in the English Midlands, that comprise the memoirs of the Victorian toast who candidly reveals himself to have been as well the cowardly bully of Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Working as editor and annotator, Mr. Fraser has published the mss. in order of their composition, which is not however a chronological one. Previous tomes depict Flashman fighting in the Afghan War of 1842, in the China War of 1860, and with General George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn (of which he was the sole, though unknown, survivor) in 1876, among other events and places; the present one is his account of his participation in (and also his absence from) the First Sikh War of 1845-46, in which the Khalsa—the great “Pure” army of the Punjab—marched on the British with the intent of driving them into the sea.

As so often in his career, Sir Harry’s most dangerous involvements in the Punjabi crisis were the direct result of his strenuous attempts at avoiding them. In this instance, however, his overriding concern for Number One led him, however unintendedly, to perform heroic and genuinely useful service to his country—for which he received precious little credit: “Most of my campaigns have ended with undeserved roses all the way to Buckingham Palace, so I can even smile at the irony that when, for once, I’d done good service (funking, squealing, and reluctant, I admit) and come close to lying in the ground for it, all I received was the cold shoulder, meekly endured . . . well, more or less.” On the credit side, as a British spy in disguise of legal diplomat to the durbar in Lahore during the months preceding the war, he had enjoyed galloping the gorgeous Maharani in her palace boudoir (“rattling royalty,” as he referred to such activity), and admiring the Koh-i-Noor diamond (the so-called “Mountain of Light”) she wore in her belly button; had his portrait commissioned by her; and finally received an indirect proposal of marriage, an idea he set decorously aside for the stated reason that, “Mrs. Flashman wouldn’t like it a bit.” For a man whose skills and interests lay almost exclusively with women, horses, foreign languages (so convenient in a pinch), and careful observation (even more so), he appears to have come through the ordeal well enough. Most importantly, he had managed to be present at the crucial battle of Ferozepore and Sobraon as a spectator, rather than as a participant. (Both engagements, by the way, are described splendidly, and with great accuracy.)

In the First Sikh War, Sir Harry’s nemesis proved to be Sir Henry Hardings, at the time Governor-General of India. Regarding him, Flashman’s evaluation is astute, from both the personal and the political standpoint:

I suspected that Harding’s aversion to me was rooted in a feeling that I spoiled the picture he had in mind of the whole Sikh War. My face didn’t fit; it was a blot on the landscape, all the more disfiguring because he knew it belonged there. I believe he dreamed of some noble canvas, for exhibition in the great historical gallery of public approval—a true enough picture, mind you, of British heroism and faith unto death in the face of impossible odds; aye, and of gallantry by that stubborn enemy who died on the Sutlej [River]. Well, you know what I think of heroism and gallantry, but I recognize ’em only as a born coward can. But they would be there, rightly, on the noble canvas. . . . Well, you can’t mar a spectacle like that with a Punch cartoon border of Flashy rogering dusky damsels and spying and conniving dirty deals with Lai and Tej, can you now?

With his assessment of the business of empire—how it is won, and how it may be held—Sir Harry is no less shrewd, and most comprehensive, in his view:

You’ll have heard it said that the British Empire was acquired in a fit of absence of mind—one of those smart Oscarish squibs that sounds well but is thoroughly fat-headed. Presence of mind, if you like—and countless other things, such as greed and Christianity, decency and villainy, policy and lunacy, deep design and blind chance, pride and trade, blunder and curiosity, passion, ignorance, chivalry and expediency, honest pursuit of right, and determination to keep the bloody Frogs out. And often as not, such things came tumbling together, and when the dust had settled, there we were, and who else was going to set things straight and feed the folk and guard the gate and dig the drains—oh, aye, and take the profit, by all means. . . . When I’m done, you may not be much clearer on how the map of the world came to be one-fifth pink, but at least you should realize that it ain’t something to be summed up in an epigram. Absence of mind, my arse. We always knew what we were doing; we just didn’t always know how it would pan out.

Here again, Flashman gives us the great canvas, noble and ignoble flung down, and overlaid with the chaos and energy of a painting by Jackson Pollock. It lacks the scientific rigor with which Marx understood the British Empire, and it wouldn’t play at Stanford University today—or if it did, it would be as Prosecutorial Exhibit Number One. It is, on the other hand, life—life as Shakespeare, Cervantes, Fielding, and Gibbon understood the word. Human—all too human.

[Flashman and the Mountain of Light, by George MacDonald Fraser (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) 365 pp., $22.00]

Leave a Reply