A reasonable case can perhaps be made for some form of firearm regulation. However, few in the opinion- molding professions are able to make it with credibility, unacquainted as they are with up-to-date, scholarly work on the issue. Many journalists who cover the subject continue to recite a collective wisdom based on the studies and analyses of the 1960’s and 70’s, and it is these views, produced mostly by activists inclined to favor stringent controls, that have formed the general public’s approach to the subject.

Now a book has appeared which is designed to help journalists—and the public —become acquainted with the gun control research of the 1980’s and 90’s. Don Kates and Gary Kleck hope to “bridge the vast gap between scholarly understanding of firearms issues and how they are generally reported and discussed in the popular media.” Both men are well qualified for the task: Kleck is a Florida State University criminology professor who has made a specialty of the study of gun ownership and use and their relationship to crime; Kates, a civil rights attorney and scholar noted for his writing on gun issues.

Both Kates and Kleck identify themselves as liberals; each appears to have arrived at his present position in the gun debate through an evolutionary process spanning many years; and each acknowledges that reasonable arguments can be framed for some types of control on the ownership and use of firearms. The authors, in fact, go out of their way to distance themselves from what they characterize as the absolutist positions taken by groups such as the National Rifle Association. Yet both men focus a critical eye on the rhetoric and goals of the gun control lobby as it has developed since the mid-1960’s.

A well-written introductory chapter by Don Kates presents an array of certain gun-related “facts” routinely cited by the media. He demonstrates how these “facts” are inconsistent with the relevant evidence established by qualified researchers, and then outlines what he sees as “the historical antecedents which helped form today’s media-based conventional wisdom.”

In general, the media’s position on this issue has mirrored the views of the antigun lobby. Not until 1981 did any serious challenge to this consensus emerge. Surprisingly, the shot across the bow was a study funded and published by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and conducted by scholars with antigun biases. The researchers were shocked by their findings:

There appears to be no strong causal connections between private gun ownership and the crime rate. . . . It is commonly hypothesized that much criminal violence . . . would not occur were firearms generally less available. There is no persuasive evidence that supports this view.

The years following release of the NIJ report have witnessed a flowering of scholarship, much of it disputing the conclusions of the two previous decades. Citing the treatment of specific gun-related issues, Kleck has little doubt that “the nation’s most important news sources do indeed shape information on gun issues in a way which encourages pro-control conclusions.” However, in keeping with this careful approach, he takes pains to disassociate himself from any suggestion that the antigun crusade is an inherently leftist enterprise, arguing instead that the media’s antigun stance is “a thing apart.” He attributes the prejudice against firearms not to any dishonest intentions on the part of reporters but to ignorance of the facts. A dubious position, at best.

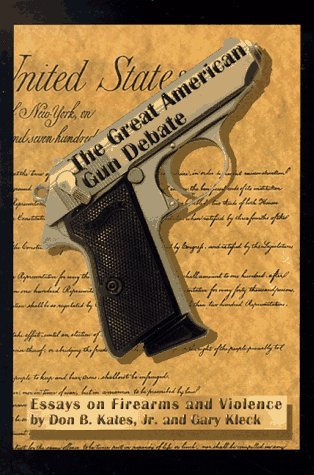

[The Great American Gun Debate: Essays on Firearms and Violence, by Don B. Kates, Jr., and Gary Kleck (San Francisco: Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy) 300 pp., $16.95]

Leave a Reply