If you live long enough junk becomes antiques, and cast-offs are classics. It’s pleasant to think that the popular culture of only a few decades ago is now revered, but it’s also scary. A recent visit to a clothing store flashing lime-green and neon-yellow polyester revivals of the 70’s was enough to remind me that not everything passé deserves recycling.

But some things do. Shakespeare himself provoked that sense in a fastchanging England over 300 years ago. And there have been times in our violent century when people knew they had experienced a creation that would outlive its time. I experienced that phenomenon myself 40-odd years ago. More importantly, I learned about it from members of the previous generation. I was impressed when veterans of combat took certain books and music and movies seriously, and I still am. What we call “film noir” was in effect made for those veterans to watch; in fact, it was, often enough, about veterans returning to a corrupted civilian life.

Of course, they didn’t (we didn’t) call it “film noir” then. They called it good stuff. You recognized it for its refusal of smarm, its gritty exception to the slick, even feminized corporatism inundating America which would be perfected later on in Bill Clinton’s public weeping. What we call “film noir” were some of the jewels among the cheap pictures. They got no respect except from the thousands who loved them.

In a sense, film noir meant men’s movies. They were violent and bleak and grim and people died at the end. The dark melodrama was where tragedy went to die. The femme fatale was familiar, not so much as a come-on but as an agent of doom related to Clytemnestra and Lady Macbeth. (Lady Macbeth’s brilliant aplomb in handling embarrassment in the banquet scene makes her the Miss Manners, if not the Martha Stewart, of her day.) To the veterans (as to all alert citizens) it did not seem strange to see a man pulling a .38 out of his jacket, nor did it seem bizarre to think that the “establishment” was corrupt, wired by the mob. The veterans had been required to kill for peace, and then to shut up and not expose all the lies when they got home.

So much for the audience. The makers of the films noirs were from everywhere, many of them European craftsmen such as John Alton of Hungary who was the greatest cinematographer of film noir. The sensibility of the films was precipitated by the tough guy writers of the 30’s, and in Faulkner and Hemingway in the 20’s. The French, responding first to the film noir cycle, gave it its name, making some of us feel a bit like the fellow in Moliere who learned that he had been speaking prose all his life. Merci beaucoup, mes amis.

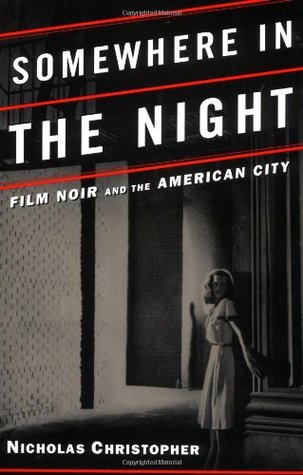

All of which brings us to the immediate occasion, Nicholas Christopher’s new book on film noir. He begins with a memory of a Parisian theater in 1973, watching Out of the Past (1947), one of the greatest of its kind. Analyzing that film and appreciating its subversive darkness and outrageous form leads him through the cycle of film noir and on to a late neo-noir such as The Usual Suspects (1995).

Nicholas Christopher is a poet and a novelist who knows what it means to follow a vision, to dwell on an image. He never backs off from tracing the implications of film noir, relating the dark visions to recent American history, the postwar boom, the Bomb, the Cold War, McCarthyism, and all the rest of them. His most striking virtue, I think, is his passionate response to provocative material, his openness to cinematic experience. He manages to deal with the films in an informed voice, but without a professorial tone. He excels at conveying the outrageousness of what he describes, incisively defamiliarizing what we remember all too well, and what still plays routinely on cable.

Sometimes there are flaws in his emphases, or slight errors or other problems.

Such as the exasperating sentence fragment/paragraph.

But otherwise Somewhere in the Night is exciting, informative, and, I think, the best introduction to its topic. The other essential books on film noir are academic and encyclopedic, serving another purpose. Silver and Ward’s Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (1979; third edition 1992) and Spenser Selby’s Dark City: The Film Noir (1984) are the best of the others, if you discount Borde and Chaumenton’s Panorama du Film Noir Americain (1941-53) (1955).

Need I add that on that putative shelf there ought also to be a host of those indispensable films that remain America’s gifts to the world? Some of the film noirs rank with the greatest productions of world cinema. Double Indemnity (1944), Gilda (1946), The Killers (1946). Out of the Past (1947), Criss Cross (1949), D.O.A. (1950), Gun Crazy (1950), Strangers on a Train (1951), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Touch of Evil (1958), and probably 50 more, plus perhaps ten outstanding neo-noirs in the last 30 years, are all films that everyone should know. Once seen they cannot be forgotten, nor can their icons. Richard Widmark, Robert Mitchum, Dan Duryca, Elisha Cook, Jr., and all the rest of The Usual Suspects constitute what we can now see—what Christopher helps us to see—as a pantheon of the modern imagination. After all, the hero had always died and gone to Hell, but never before so insistently to get out of the other hell that is the postwar American city.

[Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City, by Nicholas Christopher (New York: Free Press) 290 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply